Non-heterosexuals have way worse than average mental health. Minority stress is the very mainstream idea that this is because society discriminates against them. I wrote about why I don’t think this is true many times before. One of my main takes were that non-heterosexuality and poor mental health are genetically confounded (they are caused by similar genes). We know this because once we control for genetic effects by comparing non-heterosexual people to their heterosexual monozygotic twin pair, most of the effect vanishes. This is a common pattern, and ignoring it (also known as the sociologists fallacy) is also very common.

The other take was that although there are many quasi-experimental studies claiming to show causality (e.g. that gay people suddenly get worse after a law banning gay marriage is passed), these are p-hacked by ideologically aligned researchers and a fair reading of them is that policy doesn’t affect minority mental health.

Some new papers about this topic came out which I want to review. One is a twin study, one is a quasi-experimental study, and one is a review which proposes alternative mechanisms that can harm non-heterosexual mental health.

The twin study is:

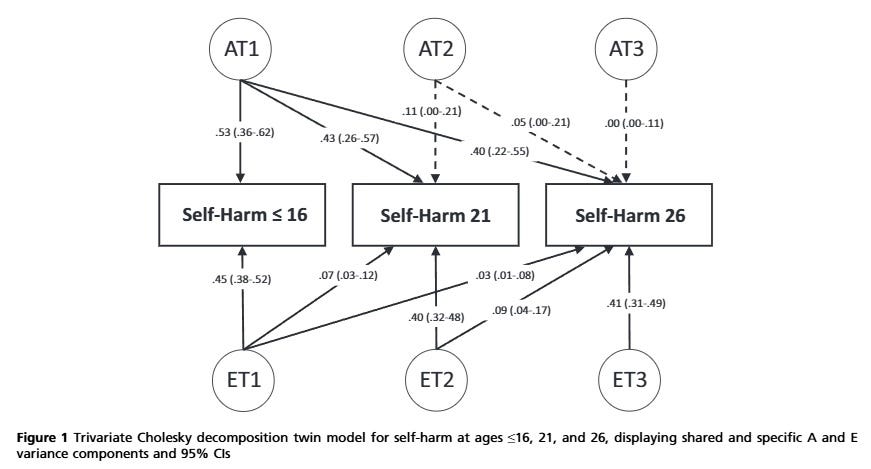

This is not really a study about “how well off are the heterosexual siblings of gays” but more about “what causes self-harm in young people”, and non-heterosexuality is one of those things. Self-harm is measured three times in the British Twins Early Development study, and the most interesting result is this:

What you need to see is that the numbers going away from the AT circles are all much bigger than 0, while those going away from ET are only like that if they go vertical. This means that the same genetic effects (AT) affect both current and future self-harm, but environmental effects are not like this. Non-genetic causes of self-harm are always strong, but not the same across the three waves. This is what the abstract summarizes as “stability in genetic influences and innovation in non-shared environmental influences on self-harm”. This is a very common finding in genetics and one of the motivations of the “gloomy prospect” hypothesis (that while genes are not everything, everything else is just random short-lasting things which are not modifiable). I note that I think this is a pessimistic reading of that literature and will absolutely go out on a limb disagreeing with Robert Plomin in his field of specialty, but that’s for a later post.

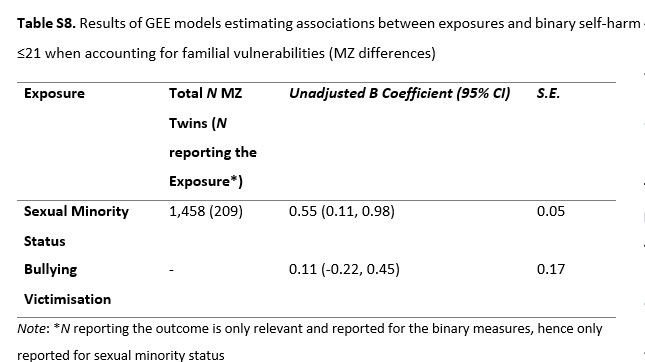

Anyway, the co-twin analysis most interesting for us is an afterthought in this paper and it is hidden in the supplement. The paper tersely says:

“These [co-twin analyses] were tested for the variables that can conceptually be unshared between twins (sexual minority status and bullying victimisation). The association persisted between sexual minority status and lifetime self harm reported at 21 ( B 95% CI = 0.11 – 0.98), but not between victimisation and self-harm ( B 95% CI = 0.22 to 0.45). See Table S8 for details. Gender minority status may be unshared between MZ twins, but it was not tested due to a small number (N = 29) of MZ twins reporting to be transgender or nonbinary.”

So even within MZ pairs, non-heterosexuality (but not bullying victimization) is associated with significantly more common self-harm. The population effect is 0.89 (Table 2) so about 38% of the association goes away after genetic control.

This is interesting but there are things I’m scratching my head about.

TEDS is a longitudinal study. It measures not just self-harm, but also sexual orientation/preference at different waves. The age 21 measure sounded like this:

" It was assessed using a single question about the sex of people to whom participants are sexually attracted, with responses including ‘Always male’, ‘Mostly male but sometimes female’, ‘Equally males and females’, ‘Mostly female but sometimes male’, and ‘Always female’. "

This is what we call “sexual preference”, similar but not identical to “sexual orientation”. For example, you could identify as a bisexual woman but have only ever had boyfriends (a common observation) – in this case your orientation is bisexual but your preference is for men.

At age 26, TEDS asked about sexual orientation instead:

“At age 26, twins self-reported their sexual orientation, with the following options: heterosexual, homosexual, bisexual, pansexual, asexual, fluid, prefer to self-define, unsure/I don’t know, and prefer not to answer. These were used for the descriptive statistics, but for the inferential analyses, the scores were dichotomised into “heterosexual” and “sexual minority”.”

The paper we are looking at now uses this age 26 measure of “orientation”.

However, while self-harm was measured at age 16, 21 and 26, we are only seeing age <21 in the co-twin analyses. Sexual orientation is supposed to affect something that took place before it was measured! Because sexual orientation is supposed to be more or less stable this would be fine if there was no age 26 self-harm or age 21 sexual preference measure, but both are available. Why not use age <26 for self-harm? Why not use the age 21 sexual preference data as the predictor, at least in an alternate analysis? Actually, how is the SE only 0.05 but the CI 0.87 units wide? The co-twin analysis in this sample was either sloppily done, p-hacked or both.

The quasi-experimental paper is

From 2018 to 2022, 48 anti-transgender laws (that is, laws that restrict the rights of transgender and non-binary people) were enacted in the USA across 19 different state governments. In this study, we estimated the causal impact of state-level anti-transgender laws on suicide risk among transgender and non-binary (TGNB) young people aged 13–17 (n = 35,196) and aged 13–24 (n = 61,240) using a difference-in-differences research design. We found minimal evidence of an anticipatory effect in the time periods leading up to the enactment of the laws. However, starting in the first year after anti-transgender laws were enacted, there were statistically significant increases in rates of past-year suicide attempts among TGNB young people ages 13–17 in states that enacted anti-transgender laws, relative to states that did not, and for all TGNB young people beginning in the second year. Enacting state-level anti-transgender laws increased incidents of past-year suicide attempts among TGNB young people by 7–72%. Our findings highlight the need to consider the mental health impact of recent anti-transgender laws and to advance protective policies.

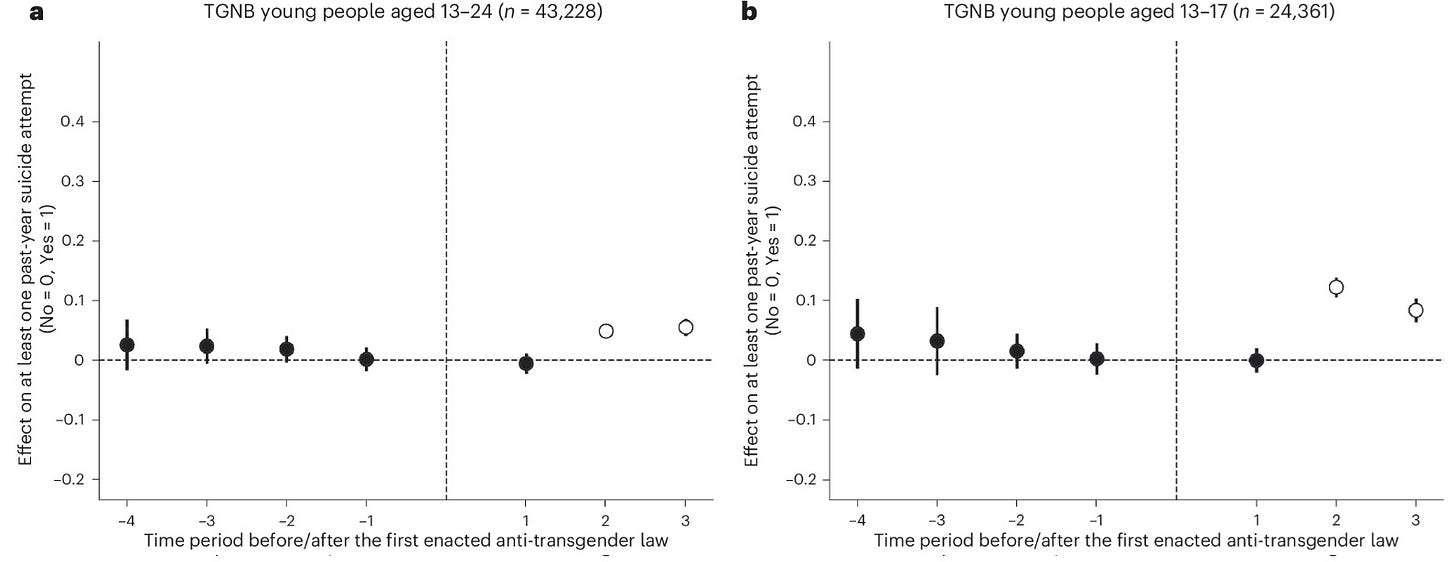

This came out in Nature Human Behavior, a very prestigious journal, although explicitly a woke one. The paper is very similar to Hatzenbuehler et al 2009, Raifman et al 2017 and Raifman et al 2020: it uses data from online samples measuring mental health in young Americans, and checks if mental health suddenly got worse specifically for “transgender and non-binary” participants after an anti-transgender law (for example, banning transgenders from women’s sports) was passed in their state. The results are weird:

The dots show the estimated change from baseline in the self-reported number of suicide attempts for transgenders after such a law was passed (vertical line). A “time period” is basically one year, with the limitation that data took some months to collect. While there seems to be a highly significant effect on suicidal attempts, it takes place in the second time period! (They hack out a first period p=0.049 by arbitrarily limiting the sample to 13-17 year olds. No preregistration.)

I think it’s strange that the YRBS-style question they use asks about the number of suicidal attempts in the past year. This must be 0 for the overwhelming majority of respondents. The study uses a linear model to estimate the number of suicide attempts, but the results replicate nicely if suicide attempts are binarized.

I note that Raifman et al 2020, the only quasi-experimental paper that otherwise doesn’t have huge red flags, doesn’t do this binarization.

The problem, other than the strange 2-year wait period before a law starts impacting transgender suicide rates, is that the effect vanishes completely if a slightly different self-report measure of suicidality (“seriously having considered suicide”) is used:

By this measure, suicidality seems to drop significantly by the third year after anti-transgender laws! If we can deviate from how a quasi-experimental study is normally done and look at not the first, but the second measure after the intervention, surely we can also look at the third. We need more anti-transgender laws to protect the youth from suicide!

The authors commendably do placebo tests by using not suicide, but homelessness and full-time employment as the outcomes:

Ironically, both measures show the exact same effect as the target measure: a significant increase two time periods after anti-transgender laws. The authors use another statistical test (a “two-way fixed-effects difference in differences” model) which doesn’t separate the dots but compares all post-treatment waves to baseline. With this test, nothing is significant. Despite what you would think, the study did not compare transgenders to non-transgenders, despite having ample data on the latter. It is a “difference in differences” study because it compares transgenders in states introducing laws to those in other states. Ideally, you would use non-transgenders as controls because maybe you are missing some trends in suicidality correlated with the laws.

Simply put, Lee et al 2024 is a misleading study, like most quasi-experimental tests of the minority stress hypothesis I saw. A common pattern is that the authors show null findings and go on to discuss them as if they showed something else, including suggesting policy. An unbiased reading of the results would tell you that this is a null effect. The effect of anti-transgender laws on suicidality is only significant long after the laws are introduced, and even then only if a specific measure of suicidality and a specific type of statistical test is used. Placebo tests which shouldn’t work end up showing the same pattern as the main analysis, showing you how easy it is to get results like this by accident. This is totally hushed up in the discussion.

I increasingly think that the correct reading of the quasi-experimental literature is simply that changing legislation about sexual minorities has no effect on their mental health.

The review paper is Pachankis & Clark: The Mental Health of Sexual Minority Individuals: Five Explanatory Theories and Their Implications for Intervention and Future Research

Pachankis is a pretty woke author, but if you read between the lines, this paper is BASED. They immediately handwave away biological theories of poor mental health in sexual minorities, and go on to suggest minority stress and four alternatives as causal environmental hypotheses:

1) Distinct lifeways: being gay means you will lead a different kind of life

2) Narrative possibilities: the groups we identify with give us a story about who we are, and maybe sexual minorities have very negative stories

3) Social safety theory: sexual minority members have fewer affirmations of safety, like supporting parents or a place in society.

4) Fast life history theory: sexual minority members are exposed to early adversity which leads them to develop a fast life history (impulsivity, risk taking, hypersexuality etc.)

The last two theories are not good. Social safety theory is the same is minority stress if you think “lack of safety” is the same as non-discrimination, and a special case of “distinct lifeways” if you think it is not. “Fast life history” is strange, and I’m not even getting into criticizing the long-debunked Freudian assumption that mental problems are caused by “early adversity”. Pachankis & Clark are unclear what they mean by this theory but there is no way to see it favorably. Does early adversity cause both non-heterosexuality and fast life history? If so, why call it “fast life history” at all? We don’t normally name causal theories by another consequence of the same cause – we don’t have a “low white blood cell count theory” of AIDS, both that and the illness are caused by the HIV virus. Or is it that the fast life history normally also present in non-heterosexuals causes mental problems? Then it’s a special case of “distinct lifeways”.

The first two, however, are bangers and I never saw them elaborated like this anywhere else.

“Distinct lifeways” says that if you are non-heterosexual, you will have different experiences, including some which plausibly impact your mental health. This is obviously true. If you are gay, for example, you will be in the minority and by definition you will not have biological children with people you are sexually attracted to (yet), which is otherwise a pretty basic human experience. These alone could make you depressed. However, especially gays and bisexuals live farther from their families, have fewer people in their lives they can rely on, and use drugs more frequently, among other things. Risk behaviors are strongly correlated with same-sex attraction. We would not expect these patterns for other minorities, though, and unlike discrimination, they don’t decrease as a society becomes more tolerant. Minority stress can’t explain why non-sexual minorities don’t have mental health crises, and why sexual minorities are not better even in more tolerant places and eras, but distinct lifeways can. Non-heterosexuality is a gateway to a lifestyle which is not good for the psyche.

“Narrative possibilities” is even more damning. If you think about it, what topics do we mention when sexual minorities come up? There is an empty reference to “pride”, but other than that the whole discourse is about overcoming oppression, fighting for mental and physical health, the various ways modern society is bad for non-heterosexuals. Every story about sexual minorities is a sad one. This victim narrative is similar to what Jonathan Haidt calls “reverse cognitive behavior therapy”: society is telling non-heterosexuals that although they should be proud of themselves for some reason and blame others for their problems, the core of their essence is that they are problematic. This cannot be good for mental health. Just like distinct lifeways, but unlike minority stress theory, narrative possibilities can explain why other minorities don’t have a mental health crisis, or why non-discrimination doesn’t make it go away. Ironically, by becoming more tolerant and woke, modern Western societies may have become worse places to be non-heterosexual by amplifying this victim narrative.

I think a combination of a shared genetic predisposition, distinct lifeways and narrative possibilities is the true reason for poor sexual minority mental health. On the one hand, non-heterosexuality is one manifestation of a heritable character which also contains impulsive and neurotic traits. On the other hand, once you are non-heterosexual, you are exposed to an unconventional lifestyle which takes its own toll on mental health. The third punch is that in modern societies you are fed a victim narrative which tells you that you are not just a normal person with a rare sexual preference but a fragile, sickly being in a hostile world.

Another study here which I think you should review. Thoughts? https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00148-025-01077-4

Excellent post. Note also that the DID methodology was also used to make ridiculous stupid claims about the putative effect of COVID masking which did nothing to prevent COVID spread.