Minority Stress Update 2

New genetically informative studies about homosexuality and mental health

Some of my previous posts were about the minority stress hypothesis. To recap, this is the idea that the reason sexual minority members have poor mental health is that they experience discrimination and harassment from the majority population, this makes them stressed, and ultimately anxious, depressed and suicidal. I wasn’t and I am still not a big believer of this theory. I think that non-heterosexual orientation is most likely tied to poor mental health at a basic, possibly biological level: people who have an “outlier” personality are outliers along multiple metrics.

One way to test the minority stress hypothesis is to compare the mental health of members of monozygotic twin pairs who are discordant for their sexual orientation. If there is no difference, this falsifies the minority stress hypothesis and actually suggests a very narrow alternative theory: there are either genetic factors (more likely because these are always important) or experiences in the rearing family (that is, in the shared environment, less likely because this is rarely important) that cause both non-heterosexuality and poor mental health. If there is a difference – homosexuals tend to have worse mental health than their own heterosexual twin brother – then the minority stress hypothesis can be true. Of course, other things can still explain this finding. For example, homosexuality and poor mental health can be both caused by trauma outside the family, or homosexuality may predispose people to experiences other than discrimination that cause poor mental health, such as participation in a hedonistic subculture. So like any good theory, minority stress theory is easier to disprove than to prove.

Because of the importance of this study design, it is good to have all twin control studies in one place. Commenter randomq pointed me to some studies beyond the ones I already reviewed and I also found some, so it’s a good idea to take a look at them and what they say.

This early study uses data from a huge Swedish twin survey completed in 2005 in over 17000 people. Sexual orientation was inferred from any/none self-reported same-sex partners, and the target variables were lifetime psychiatric disorders (general anxiety, depression, eating disorders and alcohol dependence) using a structured diagnostic questionnaire.

As it is always the case, non-heterosexuals had a higher – sometimes over three times higher – risk of having psychiatric diagnoses. An interesting thing the authors do is that they adjust these models for self-reported discrimination and hate crime victimization. These are imperfect measures – somebody with worse mental health is more likely to see an innocuous remark as discrimination or even a hate crime – but the risk actually doesn’t change that much. In other words, mental health is much worse even in non-heterosexuals who don’t report discrimination and hate crime victimization at all!

Of course what interests us the most is what happens when we compare members of twin pairs. Unfortunately, this was done here by pooling MZ and DZ twins, even though there were 409 discordant pairs (minus some attrition due to missing data) which is a decent size sample size for any twin study. DZ twins have some genetic differences so a pooled analysis doesn’t exclude all genetic factors. Still, once they do even this weaker design, the relationship between depression and ADHD scores (the only mental health variables with continuous scores) completely vanishes – look at the “Within-twin-pair” analyses below, only depression in women passes a p<0.05 threshold.

This study contradicts the minority stress hypothesis. Controlling for self-reported discrimination doesn’t really change the relationship between non-heterosexuality and poor mental health, but controlling for genetic factors absolutely does. Simply put, if you are homosexual, although your mental health is likely worse than the population average, you are not expected to have much worse mental health than your heterosexual twin brother, even if you say you experienced discrimination.

This is a small study (N=38 pairs) of MZ twins discordant for sexual orientation. The key results are in the table below. As you can see, for the majority of mental health indicators, it was actually the heterosexual twins who did worse, sometimes significantly so! (At least by the nominal p=0.05 definition of significance). You won’t get a very conclusive study out of N=38 but this is one small strike against the minority stress hypothesis.

This is a study of 38 MZ twin pairs discordant for sexual orientation, pretty much explicitly recruited (online) to test the minority stress hypothesis. They measure lots of different types of wellbeing, such as depression, wellbeing, rumination as well as “proximal stressors”, the presence of discrimination experienced for being a sexual minority. These latter were, expectedly, strongly significantly different between MZ pairs: of course only the homosexual twin can even perceive to be discriminated against for being homosexual. As in many other studies, there were no significant differences between twins of different sexual orientation in depression or anxiety, but the authors make a lot of a p=0.025 rumination difference. An interesting phenomenon that underscores this as maybe not totally fake is that twin difference scores in rumination are correlated with some three out of six forms of experienced discrimination. In other words, the more discrimination a homosexual reports, the larger his rumination difference compared to his heterosexual twin pair. The authors seem to imply that this is akin to a dose-response relationship, but it’s just as possible that some homosexuals identify more with this idea that as homosexuals they are a persecuted minority and give high discrimination and low mental health ratings accordingly.

Again, not very conclusive with N=38, but from 3 mental health indicators only one showed a significant difference in favor of heterosexuals, and not necessarily the one (depression or wellbeing) most implicated by minority stress theory.

This study leverages a large Swedish twin study of 18 year olds who reported their sexual orientation (dichotomized by the authors as “heterosexual” and “non-heterosexual”) and many measures of mental health and wellbeing. 8.3% of respondents identified as something other than heterosexual, which is impressive given that these responses were collected between 2000 and 2018, so most of the sample came before non-heterosexual identities started skyrocketing in adolescents. There were 119 same-sex twin pairs discordant for sexual orientation.

The results were quite typical. Non-heterosexuals reported much worse mental health across the board using many different metrics, every one of which returned a significant difference, mostly with very convincing p<0.001 p-values (look at the “Between-Family Comparison” columns in the table below). But once heterosexual and non-heterosexual members of the same twin pair were compared with each other, all these differences vanished completely (“Within Same-Sex Twin Pair Comparison”).

Using just any “twin pairs”, even if they are same-sex twin pairs, is always sub-optimal. The authors say that their sample was too low to do separate MZ and DZ twin analyses – not really true, they would have had more than the 38 the previous two studies had as about two thirds of same-sex twin pairs are MZ twins, a fact you can use to run proper twin models even if you only know the sex but not the zygosity of twins. In any case, same-sex twin control is the weaker model, and even this one completely falsifies the minority stress hypothesis, at least in this study. Once we compare for familial – shared environmental and genetic – common causes of non-heterosexuality and poor mental health, there is no relationship, suggesting that non-heterosexuality is not a cause of poor mental health.

Another Swedish study! While none of the previous twin studies used their full potential and used MZ twin comparisons, they returned mostly negative findings using just any kind of “twin control”. I hope you are following my logic when I say this is fine: if even this weak design returns negative findings, you can likely refute the minority stress hypothesis. You need the stronger design – MZ controls, fully controlling genetic causes – if the pooled or DZ control design still shows better mental health in heterosexuals: in this case, you have to zoom in to see if it goes away in a stricter design.

In this study, you can’t do this because this is a sibling control study. No twins, only 1154 sexual minority members (heterosexuals or bisexuals) linked to their heterosexual siblings and a lot of healthcare use data. The results look like this:

The “secondary analyses” on the right are the ones most authors run first: just comparing sexual minority members to heterosexuals, no fancy within-family design. As you can see, mental health is worse across the board, as usual. In the interesting part - when we compare people to their siblings – you see a big drop not just in the number of significant findings (that could just be the sample size, although N=1154 pairs is decent), but in the odds ratios as well. Actually, in sibling comparisons, those with worse mental health seem to be not even the gays – they have higher rates of depression, just significantly so, but nothing else – but the bisexuals. They have significantly elevated – almost doubled – risk for three out of the six diagnoses. This of course, can be just self-selection: bisexuality is much more of a fad than bona fide homosexuality, showing the strongest age and period trends, and it is likely that of two siblings, it is going to be the less mentally stable one that identifies as bisexual if this is where the winds of the zeitgeist are blowing.

This is an interesting study but it is not a good test of the minority stress hypothesis because it cannot control for genetic confounding without MZ twins. Even so, evidence in line with the minority stress hypothesis is circumstantial: gay people, presumable those with the more stable and more extreme identity have elevated rates of depression compared to siblings, but overall not significantly worse mental health.

In addition to these papers, there are some very interesting ones written by Nigerian researcher (currently working in King’s College) Olankule Oginni. Some were even covered in the news. Two very similar papers – same method, different sample – are these:

One other I do not analyze, because one of the newer papers which I do look at contains a more on-point analysis of this dataset:

The first is an analysis of a large Finnish twin cohort (N=8172) and the second of Plomin’s favorite British TEDS (about 9000 people). All are young people. These samples also have molecular genetic data from both twins, which enables the construction of polygenic scores and fancy causal analyses. Let’s start with what we already know: Cholesky decomposition, genetic and environmental variance components. Why does sexual orientation correlate with poor mental health – is it a common genetic or a common environmental cause? In other words: is mental health and sexual orientation more strongly correlated in MZ than in DZ twins? That would suggest a common genetic cause.

Both studies concur that same-sex attraction is much more strongly related to poor mental health in MZ twins, suggesting a common genetic factor, just like in the Zietsch papers I reviewed in my first post. Genetic and nonshared environmental correlations between same-sex attraction and mental health look like this:

So most of the shared variance between sexual orientation and psychological problems is in fact, even according to this study, is genetic! Remember that it is essentially the environmental covariance we are estimating in MZ controls. It looks low, but non-zero here. (By the way, same-sex attraction looks really heritable here, at 54% in the British and 57% in the Finnish sample!)

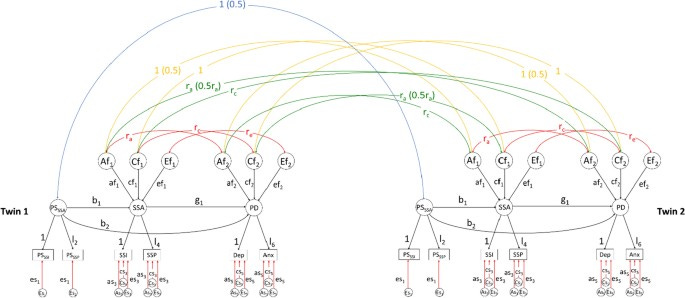

The next step is the fancy part. Buckle up. Using genetic data they could fit a model called Mendelian Randomization-Direction of Causation (MRDoC). This is probably the best illustration of what’s going on:

This is a Mendelian randomization and a twin model combined. Look at the black horizontal paths at the bottom. You have a polygenic score for same-sex attraction (PSSSA), derived from this GWAS: basically a genetic estimate of the probability of you being gay. One thing this can cause (b1 path) is, well, you being gay (SSA, same-sex attraction). Another thing it can cause, independent of this, is psychological distress (PD) – this is the curved b2 path. Note that it circumvents the “being gay” part: this path estimates the effect gayness-causing genes may have on psychological distress even in people who are not themselves gay. This is what we call horizontal (in normal language, biological) pleiotropy: one genetic variant directly affects multiple traits, and a strong version of a rival theory of minority stress is that gay people have poor mental health because the genetic causes of these traits overlap at a very basic genetic level. On the other hand, g1 is a causal path from same-sex orientation to poor mental health – “causal” in the geneticist way of speaking English, meaning that if you have more genes, you have more of the phenotype, a route of causation that can only go one way (barring retroviruses and other crazy outlier events).

As it happens, in both of these papers the b2 paths are, while positive, non-significant, while the b1 and g1 paths are significant, suggesting that same-sex orientation really has a negative effect on mental health, but there is no proof for biological pleiotropy (“gayness-sadness genes” that make you have poor mental health even if you are heterosexual). The authors make a big deal out of how this is “consistent with existing evidence and theoretical frameworks implicating minority stress-related processes and provide justification for ongoing efforts aimed at reducing psychosocial disadvantage experienced by sexual minority individuals” – guaranteed to be soon picked up by the press and activists as “the minority stress hypothesis is proven”.

However, as fancy as this design is, it doesn’t really do what it is advertised to do.

The first problem is that the polygenic scores used here are not great. The correlation between the same-sex attraction polygenic score and actual same-sex attraction is 0.06 in one study and 0.08 in the other – over 90% of the genetic variance is unaccounted for. There is a signal here, obviously, but the absence of a correlation – such as the absent b1 path – can be just a power or an indicator quality problem. What would the other genes do if we knew what they are?

The second problem is that the causation appears to work both ways. Yes, having same-sex attraction makes it more likely that you have poor mental health and have more risky sex, but the reverse is also true! Having genetic variants associated with poor mental health or risky sexual behavior is also associated with being non-heterosexual, with not much of a vertical/biological pleiotropic path. This is obviously not the authors’ conclusion but if you follow their logic you can say that if you have poor mental health or if you like risky sex you are more likely to give that LGBT identity you saw in the Coca-Cola commercials a try, which I don’t think is necessarily wrong but it’s not exactly PC.

The third problem is that if the MRDoC models are full of strange results. For example, in the British sample, they try using self-reported victimization as a mediator between same-sex attraction and mental health – you get poor mental health as a sexual minority if you are victimized. This is not what the data shows. Having same-sex attraction is not causal for victimization at all, however, victimization and poor mental health are causal for each other! I think these models are not great at distinguishing causation unless it’s about confirming or disconfirming very specific genetic effects.

Overall, these are interesting papers but there is not much new or conclusive in them. “Known genetic variants have a horizontal pleiotropic effect on mental health” is a very specific alternative hypothesis to minority stress theory which is proven wrong, but doesn’t strike at the heart of the issue. We know – even from these samples – that most if not all of the sexual orientation-mental health correlation goes away once we control for common genetic causes within MZ pairs, we know that ethnic minorities don’t have mental health crises similar to sexual minorities despite discrimination, that sexual minorities have poor mental health even in highly tolerant societies and this disadvantage didn’t decrease much as tolerance increased over time, and we know that there are huge problems with pseudo-experimental studies of the minority stress hypothesis and once you look at that literature critically, it doesn’t support this hypothesis at all.

After reviewing these new studies, I am reassured that the minority stress hypothesis fails serious empirical tests and its popularity has more to do with its political than its scientific grounding.

Hey, was wondering if you have seen some of the studies about minority stress/the stigma hypothesis from here: https://balkrai.wordpress.com/2023/08/08/sobre-la-adopcion-homoparental/

It's in Spanish, but nothing a translator can't solve.

You missed this important paper: https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamapsychiatry/fullarticle/481699

"The differential pattern of differences for men and women can also be interpreted in various ways. First, an effect of sexual orientation in women might be more difficult to demonstrate since women already show higher levels of mood and anxiety disorders than men regardless of sexual preference... The fact that homosexual men showed higher prevalence rates of disorders that are characteristic for women in general, whereas homosexual women showed higher prevalence rates of disorders that are characteristic for men in general, is in line with the theory that sex-atypical levels of prenatal androgens play a major role in the causes and development of homosexuality"