I recently wrote about the minority stress model which is supposed to explain worse mental health in non-heterosexuals. I didn’t find this theory very convincing, at least not in this case. But there are plenty of other communities in the West or in other countries that, just like non-heterosexuals, at least allegedly suffer from discrimination, so it would be easy to imagine that minority stress also affects them. In fact, this is explicitly part of the original theory. Minority stress theory pioneer Ilan Meyer writes:

“Social stress might therefore be expected to have a strong impact in the lives of people belonging to stigmatized social categories, including categories related to socioeconomic status, race/ethnicity, gender, or sexuality.”

The minority stress model is not in itself unreasonable. It is easy to imagine that belonging to a discriminated against or politically repressed community causes you stress which collectively depresses the mental health of that community. Studying minorities other than non-heterosexuals is actually a pretty strong and reasonable test of this theory.

So how are the other minority victims of – at least alleged – discrimination and repression doing vis-à-vis their mental health? By this I mainly mean non-white communities in the US and UK, both because the best data exists for these minorities, and because both politicians and the public in these countries are especially interested in rooting out any form of ‘racism’ that negatively affects non-white communities. If we stick to our guns about what discrimination can do, these minorities should obviously suffer from worse mental health the same way it is with non-heterosexuals.

To my surprise, there appears to be very little literature explicitly talking about ‘minority stress’ affecting the mental health of any minority other than non-heterosexuals. Whenever non-whites are studied, it is usually also in context of a particular sample which also belongs to a sexual minority. Very strange, given how obviously the minority stress model could be applied to, well, minorities. Minority mental health appears somewhat understudied in general, especially outside the United States – we will soon see what this means.

Sorry to be boring and not get to the point but some more words need to be said about ‘mental health’. Mental health is hard to define or measure. How would we even know if a minority has worse mental health? There are several ways to do that. Obviously neither is perfect.

Well, the first thing we can do is administer a screening questionnaire like the CES-D. Such a questionnaire is a collection of very direct questions about symptoms of depression or other psychiatric illnesses; this is why they are also called symptom checklists. The CES-D looks like this:

These scales have some great applications and they are shown to have way over zero validity, but I understand if you are not very impressed by them at first sight. This is not exactly like a blood test for diagnosing an illness (although to be honest probably no serious psychiatrist in the world would diagnose you with anything based on just a screening questionnaire). What if you lie about your symptoms? What if you belong to a particular culture which encourages or discourages you from reporting symptoms like these? What if you have your own idea of what “happy” or “depressed” means? Another big problem is that there are many such questionnaires; their correlations are not especially impressive (meaning that you could be seriously depressed according to one particular scale and quite OK according to another one). But even if you use the same scale, two people could get the same score reporting quite different symptom profiles – just imagine somebody reporting maximum levels of the first 10 symptoms and zero of the second 10, and another person with just the opposite profile. The problems don’t even end here. These scales are supposed to distinguish the “mentally ill” from the “healthy”, that is, tell if you have an illness or not, the distribution of scores people get on them is actually quite continuous and the cutoff between healthy and sick is basically arbitrary. Some people have diabetes and some don’t and doctors always want to (and need to) think about such binary diagnoses, but “depression” is more like height, while some people are obviously “tall”, most people are about average and the distribution is continuous. A leading researcher of depression, Eiko Fried wrote a great and easy-to-read paper on these issues recently.

The second thing you can do is to administer a structured interview. You can theoretically give a symptom checklist to a room full of people and not even talk to them, but with this method you need to do a long face-to-face interview. A structured interview is “structured” because you have a set of questions to ask and you will code the responses objectively, but it is still a conversation and the respondent talks to the psychiatrist like he or she wants to. These are much more detailed measures. A sample part of such an interview, the DIS (about alcohol use) looks like this:

The cultural issues are not fully resolved with these, but the questions are much more concrete and there are benefits to using a face-to-face interview.

A third method you can use is to use suicide rates. Suicide rates are a good measure because a death by suicide is a very unambiguous and very objective event which is expected to go on record. If you know how many black or white people committed suicide out of a population of how many, you have a very exact measure in your hands. However, there are big problems with this. You could theoretically have worse mental health in a group but a lower suicide rate, for example because they have a cultural stigma against suicide or because while their mean mental health is worse, they are still underrepresented among the most serious cases who commit suicide (technically, they have a lower mean but also a lower standard deviation). You also won’t know why each person committed suicide: suicide can be a complication of very many psychiatric illnesses, some of which are expected to occur due to minority stress according to the theory (most notably, depression), while others (like schizophrenia) have a more purely biological origin.

So neither method is perfect, but I think we can agree that if the minority stress model is correct, then they should all agree that the minority groups we are discriminating against – for example, black people in the US – have worse metrics on many, most, or – most favorably for the theory – all of them. This sure is the case of sexual minorities, which is why we invoked the minority stress model in the first place.

Talk over: let’s get to the numbers! As it happens, there are some very detailed studies about minority mental health. A great source for learning about the study of minority mental health in the US up until 1991 is Vega & Rumbaut. It’s literally titled “Ethnic minorities and mental health”, and has two excellent literature summary tables which I reproduce here in full. The first table is about symptom checklists like the CES-D. It looks like this:

The second is about the DIS structural interview. It looks like this:

It actually discusses many more studies than these, so many that I’m struggling to summarize it in a blog post-friendly way. Early in US history there were early reports about both lower and higher rates of psychiatric illness in blacks, but these were not representative studies. A representative study is very important in this case – you need to get up and sample a bunch of people who really “look like America”, because otherwise you get all kinds of biases. For example, some early researchers noted that there are few black people in mental hospitals – but is this because they don’t have psychiatric problems, or only because they don’t go to a hospital if they have one? Maybe they just don’t have the money, they don’t trust the system, or the hospitals don’t even admit them – we are talking about pre-WW2 America.

The first representative by the NCHS came in 1960-62 and found worse mental health in whites. The second was the HANES study in 1971-75 (published in 1980) which found worse mental health in blacks using the CES-D. Then there were the Epidemiological Catchment Area surveys summarized in Table 3. These were representative surveys of multiple cities with almost twenty thousand participants. A huge study was conducted in Florida in 1983-86 using the DIS. The results are a bit all over the place. Blacks usually score worse on symptom checklists, but the difference goes away if we control for socioeconomic status.

Sidebar: people interested in IQ research just cringed. Yes, it is usually a bad idea to control for socioeconomic status because it is often not a cause, but a consequence of things. But not here. The idea is that just by being black you are exposed to stress in addition to what you would otherwise experience. If this is mediated by SES – that is, you are black, this lowers your SES because of discrimination or genetics or whatever you believe, and you are worse off mentally because of this – then minority stress theory is falsified. Strictly speaking, minority stress theory says that just by belonging to a minority you experience more stress and this alone makes your mental health worse. If the effect is more roundabout than this, then you need a different theory. I should also note that as I wrote before, SES mostly doesn’t even cause stress or worse mental health because its effect goes away in genetically informed designs.

Using the structural interview method, the effect reverses and whites seem to have much worse mental health. This paradox apparently sometimes exists even in the same sample which sample the same people using both methods: black people report having more problems at the moment, but when they are asked in an interview if they seriously suffered from similar problems in the past, they say ‘no’.

The trends are broadly similar for Hispanics, although it matters a lot what kind of Hispanic we are talking about. Asian results are all over the place depending on which group we are studying exactly, and often they don’t have comparison samples from other ethnicities. For all the obsession the American public and politics has had with past grievances about ethnic minorities for the past sixty years, the researchers don’t seem to have really bothered to go to something like an Indian reservation to administer their instruments. Overall, the evidence up to 1991 doesn’t convincingly suggest at all that American minorities have worse mental health than whites.

An updated study of this same question is Breslau et al 2009: “Lifetime risk and persistence of psychiatric disorders across ethnic groups in the United States.” This is both a very nice historical summary with even more background, and a huge empirical study of almost 6000 Americans in a nationally representative sample. It uses the CIDI as its instrument. This is a diagnostic interview, similar to the DIS, but extended to better measure the current problems (not only lifetime problems), and it was quite explicitly designed to be culturally valid – the first “I” stands for “International” after all. The main results look like this:

Whites have pretty much the highest rate of all problems, compared to both blacks and Hispanics. Sometimes the results are significant, sometimes they are not, but the trend is almost always like this. The last 4 rows, “12-month prevalence among lifetime cases” is different though. What is this? It tells you that (and it is also corroborated by some other analyses the authors do) psychiatric illness is rarer, but also more persistent among minorities. They have these problems less frequently, but if they ever had them, they are much more likely to have had it recently as well. This is an interesting finding: maybe minorities don’t seek psychiatric help for their problems, or maybe whites are just more sensitive and report a mental health issue more easily, even for flimsy and transient problems that tend to go away. But blacks and Hispanics, despite all the historic and supposedly current discrimination they had to endure, do not suffer from higher rates of mental health problems like sexual minorities do. Although I think blacks and Hispanics are the most interesting groups, I am noting that there is another great study on Asians (Xu et al 2011), with surprisingly similar results: pretty much all psychiatric illnesses are rarer, but more persistent.

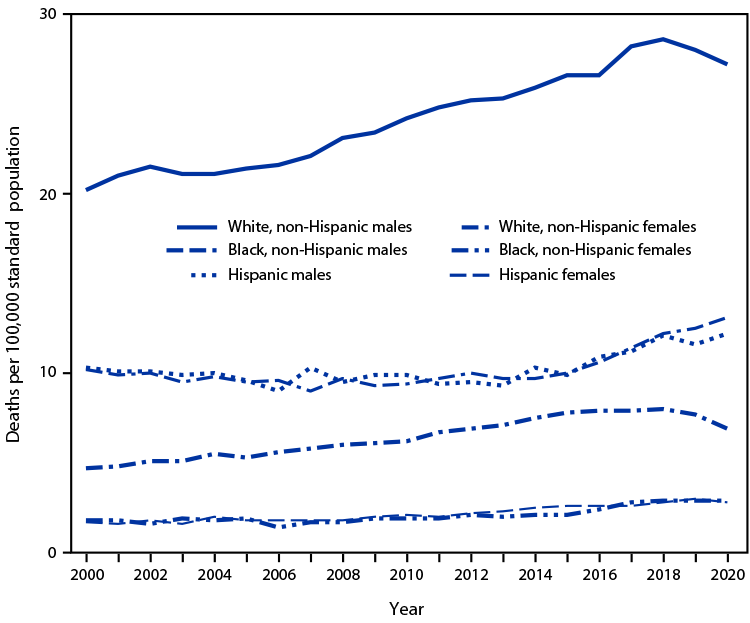

What about that third, most objective method – here are suicide rates by race in the US:

It is clear that US whites (especially white males) do much, much worse than just about any other ethnicity (Indians and Alaska Natives, not shown on this particular chart, are doing worse and may actually be a population where minority stress theory holds). One can also see the famous deaths of despair, the increase in suicide (and alcohol- and drug-related deaths) in working-class white males.

What about the UK? The UK is also becoming an increasingly “diverse” country, and it’s not like its official and unofficial organs don’t decry “racism” as the root of all evil. So if British society is just as racist as American society, maybe non-white inhabitants have worse mental health.

British epidemiologists are vastly behind their American colleagues to settle this issue. But there are a few studies I found which compared White British and non-white rates of various problems. Let’s look at them!

The sample is representative for UK minorities, with White British controls. The authors make it about the fact that minorities who report more discrimination also report worse mental health (so basically the minority stress model, although they never use this word). This is true, but of course correlation is not causation: maybe it’s just that people with worse mental health are more prone to notice (or imagine) insults of all kinds. The key table looks like this:

Look at “Common mental disorder” (based on the RCIS, a structured interview). The Irish have by far the highest rates, White British are a close second, and actual minorities have much lower rates. Notice also that while non-whites complain more about job-related problems, the Irish also report the highest rates of “Insults regarding race or religion/language”.

This is the same data source. The outcome variable here is suicidal ideation. This is the key table:

So again, just about every ethnic minority has lower – sometimes much lower – rates of suicide ideation than the White British, a finding which replicates across age groups. A notable exception is the Irish, especially middle-aged Irish men. Note that the Irish also had surprisingly high rates of common mental disorders in the other study. I don’t know why this is, but ethnic minorities, despite all the racism they have to at least allegedly endure, sure don’t have higher rates of suicidal ideation!

What about actual suicide? This chart is from the Office for National Statistics website:

So totally in line with survey data from the UK, and also much like in the US, Whites actually have much higher suicide rates than ethnic minorities (except for the Mixed/Multiple category, which didn’t appear in the surveys). Note that this is age-standardized data, so it’s not because the different age distributions of the majority and minority populations.

So overall, the result are very similar in the UK and the US. Depending on which indicator and which ethnic group we look at, minority groups have at worst equal to, but possibly substantially better mental health than the majority population in both countries. Although these groups are also supposed to suffer from discrimination, their mental health patterns are starkly different from sexual minorities in whose case we assumed discrimination to be the cause of poor mental health. This observation, the idea that these countries discriminate against minorities and the minority stress hypothesis simply cannot be true at the same time.

How do we square this circle? I have a simple suggestion: although the minority stress hypothesis may be true in specific cases (belonging to a group which is systematically discriminated against can affect your mental health), ethnic and sexual minorities in Western countries are simply not discriminated against at all. Any problem they suffer from is endogenous and not caused by discrimination by the majority, in part because discrimination doesn’t automatically cause collective poor mental health and in part in this case the discrimination doesn’t exist at all. Ironically, it is lower-class majority groups in these countries – working-class Whites – who have mental health indicators in line with being victims of discrimination in the framework of the minority stress hypothesis.