Bad things happen to good people. And to bad people too, probably even more often. Things are not nearly as bad as in, say, Early Modern England where a very substantial minority of people literally died as children, but the slings and arrows of outrageous fortune are unavoidable. The question is: does trauma really psychologically scar us even if we survive it – that is, do people who survived hardship have worse mental health later on?

Lay knowledge and probably most psychologists would respond with a resounding “yes”. I’m in contact with a lot of clinical psychologists and they seem fairly convinced that 1) past traumas are often the best explanation of a person’s current problems and 2) if a person suffers trauma now, that is in a large part a bad thing because he/she will suffer its consequences a long way down the road. Now, I didn’t interview any psychologists for this post so you have to take my word for this, however, you can see for yourself that the DSM-5 lists “childhood trauma” or “childhood sexual abuse” as a risk factor for just about every diagnosis it contains. However, considering what psychologists learn about the most important and highest-quality subfield of psychology, IQ research, we probably can’t take their word at face value.

So, what do the numbers say?

It is without a doubt that if you ask people with all kinds of problems – mental health problems, physical problems, drug abuse, criminal involvement, the list goes on – they will virtually always report all kinds of problems in their past. (My best source on this is my native Hungarian – you can have it Google translated or something if you want a collection of studies. I’m not looking up an English-language review just to point out that – as you will see – these studies follow a faulty design.) I’m afraid most psychologists would already stop here and declare victory – but you can’t really believe these retrospective designs.

The problem is that people don’t have perfect memory: what we recall is strongly affected by the circumstances and the cues we are given. As Elizabeth Loftus warns in her chapter here and as many hapless American childcare workers, not to mention Brett Kavanaugh discovered, it is actually quite possible even to implant people with false memories of trauma. In the right environment, for instance under the high pressure of a courtroom or in the intimate, mysterious atmosphere of psychotherapy people can be convinced that their kindergarten teachers celebrate black masses for the devil or that they were raped at a party 40 years ago, even though they couldn’t remember any of it for years. Of course there is no need for things to be this dramatic: we can misremember or even hallucinate much more mundane trauma. When we are down, it is easier to notice or remember bad things, so much so that negative thought patterns are often used a diagnostic criterion of depression. For somebody who is depressed, has cancer or is in prison, the past can seem much darker than it really was. My favorite story about this comes from this paper by leading trauma researcher Cathy Widom (which you should read in full if you are interested in this topic):

" Stott found that mothers of “mongol” children reported more shocks during pregnancy than mothers of children without Down’s syndrome, thus concluding that socio-emotional factors played a role in the etiology of Down’s syndrome. Since later research identified chromosomal abnormalities as the cause, it is possible that these mothers exerted extra cognitive effort in trying to recall pregnancy-related events. Another possibility is that ordinary events were redefined as traumas by mothers of affected children in an effort to explain their child’s condition. "

So yeah, following the logic of retrospective trauma studies you could believe that even Down’s syndrome is caused by trauma!

At this point that you should be seriously suspicious of self-reports of trauma. But there is data on how much this suspicion is warranted.

This is from Andrea Danese (2020), another top researcher in this field, using data from a recent meta-analysis. In his own words:

“The agreement between prospective and retrospective measures of childhood maltreatment was poor, with kappa = 0.19 and narrow variation (95% CI = 0.14 – 0.24) but significant heterogeneity across individual effect sizes ( I2= 93%). […] We found that the agreement did not differ according to whether child maltreatment was prospectively assessed through records (e.g. child protection records or medical records), reports (e.g. questionnaires or interviews) or mixed measures (e.g. records and reports). However, agreement was higher when retrospective measures were based on interviews rather than questionnaires. We also found that agreement was higher in studies with smaller sample size, possibly reflecting the use of more detailed retrospective assessments [or publication bias – East Hunter].”

This is eerily similar to the words of the Widom commentary 16 years earlier:

“Henry, Moffitt, Caspi, Langley, and Silva (1994) compared the extent of agreement between prospective and retrospective measures across multiple content domains in a large sample of 18-year-old youth who had been studied prospectively from birth. They found reasonable correlations for relatively “objective” information (residence changes, reading skill, height and weight), while psychosocial variables (i.e., reports about subjects’ psychological states and family processes) had the lowest levels of agreement between prospective and retrospective measures. […] Williams (1994) interviewed adult women, all of whom had been sexually abused during childhood, and reported recall of the victimization by approximately 69% of the sample. Widom and Morris (1997) found that between 41 and 67% of the documented cases of childhood sexual abuse among females followed up into young adulthood retrospectively reported childhood sexual abuse.” [emphasis added]

There is a lot to unpack here! Apparently, many – maybe even most – people who report abuse at one point in their lives just forget it when asked at a later time. On the other hand, also many and possible most people who report at time X+T that abuse happened at time X did not actually report it at time X! There may be a lot of reason to do so. Maybe people just get over trauma to the extent that they literally forget it, maybe they don’t realize how bad something is until later, or maybe some cases of trauma don’t go on record for practical reasons – for example, some people might be abused by their parents but don’t go to the police because they don’t know how or because they are afraid. But the raw numbers are just brutal – look at how little overlap is between those circles! I think the charitable conclusion to draw here is that “we must be extra careful to take retrospective reports of trauma at face value, and we should know that most trauma will eventually be just forgotten”, which is already a big deal compared to, for example, how Blasey-Ford’s trauma account was received (it almost cost Brett Kavanaugh his Supreme Court nomination). The not-so-charitable conclusion – and frankly I think this is closer to the truth – is that trauma reports are just worthless because they are a mish-mash of actual events, false memories and lies. Talk about a bitter pill to swallow!

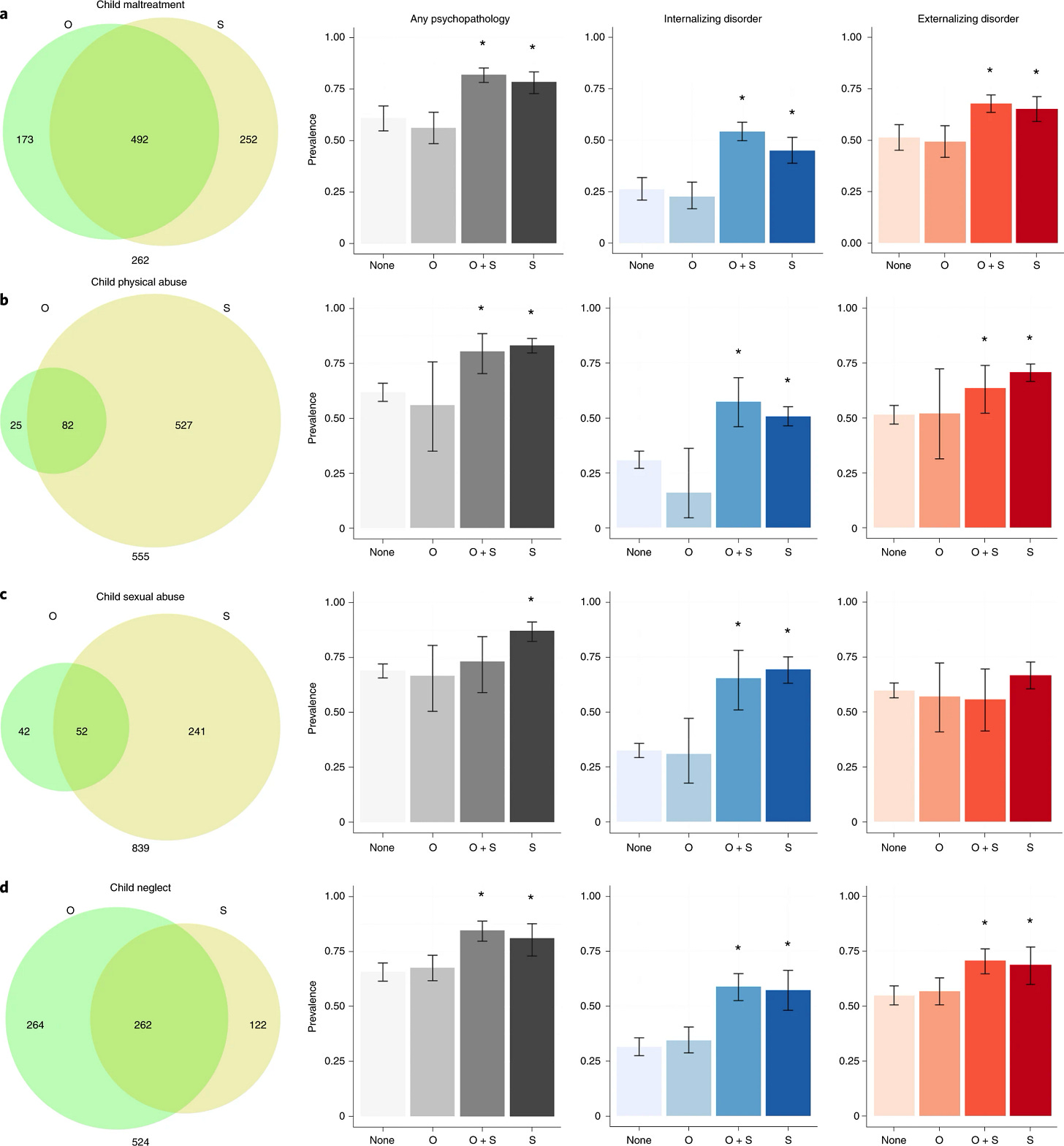

There is yet another study – also by Andrea Danese and Cathy Widom – which is worth looking at. These two people used data from a very unique cohort. In 1967-71, an American cohort was started with 908 kids who were victims of either abuse or neglect based on court records – there is no doubt that their problems happened. A matched group with no such records was chosen (N=667), and in the early 90s both groups were interviewed, among other things about 1) retrospective reports of abuse 2) current and lifetime psychopathology. Using this longitudinal cohort with objectively determined victimization, we can ask the following questions:

1. What percentage of definitely victimized kids even remember it 20 years later? What percentage of apparently non-victimized kids (of course their cases may have flown under the radar) way that they were victimized?

2. What are the rates of mental illness in kids who a) were court-proven abuse victims and remembered this, b) were court-proven victims but forget, c) did not have court cases but reported abuse, d) did not have court cases and did not even report abuse?

Here are the results in one picture:

“O” means objective and “S” means subjective. As you can see, the overlap is not great: especially with sexual abuse, most people who report it do not have court cases to back it up, and even among those with court cases about half just forgot 20 years later (or at least chose not to talk about it). The Cohen kappa is 0.25, which is higher than in the Danese meta-analysis, but still very poor.

The juicy part is the right side of the figure. See how the O+S and S columns are much higher than “None” or just O! This is the main conclusion of this paper: it is subjective, not objective victimization which predicts poor mental health. People who were victimized based on court records were not necessarily more mentally ill than those who had no court cases and reported no abuse: but those who did report abuse were also no more unhealthy if they had a court case to back this up. This doesn’t quite prove that “child maltreatment doesn’t cause mental illness, it’s just that mentally ill people are more likely to falsely report having been abused“, but it is very much in line with it. A more charitable – but I guess for most clinical psychologists still scandalous – reading of the data is that “most people fully recover from trauma and retrospective maltreatment reports are unreliable”.

This is probably a good time to stop for a second and remember that people in the past have gotten in big trouble for noticing that most people who suffer from trauma actually live on to have a kickass life. I’m talking about of course the Rind et al meta-analysis, a unique study which caused such a scandal that it was denounced in an unanimous statement by the US Congress, has its own Wikipedia page and (I’m referring to the Wikipedia page here) ridiculed by bird-brained radio host Laura Schlessinger who didn’t understand what a meta-analysis was. You haven’t done troll science until you achieved something like this! Rind collected a series of retrospective reports from college students about sexual abuse and mental health metrics. They found that even in this very biased design, there was not that much of a difference in the mental health of the abused and the non-abused. They were thoroughly criticized by other scholars, but a re-analysis of the findings confirmed their numbers: there is about a d=0.2, r=0.1 relationship between abused and non-abused college students in terms of mental health, which is statistically significant but not big, so there is no evidence that even those with self-reported abuse as that much worse off or that abuse is a major determinant of mental illness. (See here for a more up-to-date meta-analysis on largely the same topic – I’m not reviewing it in detail because retrospective studies are a flawed design no matter what.) I’m trying not to put disclaimers and trigger warnings in my posts but this is a time I’m making an exception. From my reading on the literature my impression is indeed that trauma doesn’t maim you for life. This is a testament to human resilience, and not a defense of people who traumatize. Trauma can be bad on its own, even if victims bravely live on. We shouldn’t protect children from harm because we can save money on mental health services when they grow up – we should protect them because harming children is wrong. Disclaimer over.

How do we get out of this mess, how do we deal with the fact that we can’t use retrospective reports? It superficially sounds like a good idea to do a longitudinal design: ask people at age X about trauma and at age X+T about some other bad thing that can be a consequence of trauma. As a matter of fact, a meta-analysis of such studies has recently been published. This paper summarizes 23 studies which measured trauma exposure at one point and some possible consequence at a later time. The first thing we should notice is that they only identified 23 such studies, all of them published after 2000 and almost all after 2010. Now, lots of people go to a psychiatrist, psychiatric diagnoses are virtually all based on the DSM-5, it is these (or the analogous ICD) diagnoses that your health care provider pays for, the DSM-5 handbook lists “childhood sexual abuse” or “childhood trauma” as risk factors for almost all diseases it contains and has done so for decades, yet even as of 2019 these authors only found 23 longitudinal studies which can sort of-kind of establish something like that! Psychiatry is not the brightest light bulb in the chandelier of medicine.

The second thing we can notice is that their findings were resoundingly positive. Reporting various types of maltreatment/trauma was associated with something like a 3x higher odds of developing various kinds of mental health problems, even in this longitudinal design. (There were some publication bias tests which mostly came back negative, but power was low due to the low number of studies.)

But the third thing we can notice is that it doesn’t really mean anything at all for causality. OK, so people who report being bullied, neglected or have a parent die early (these are some of the trauma categories actually considered in this paper) really develop mental health problems later. This is good to know, but what if the trauma itself is the consequence of a pre-existing problem – for example, what is bullies pick out the emotionally weakest kids who would (and do indeed) develop mental health problems anyway? What if longevity has a negative genetic correlation with mental health, so relative of people whose parents die early have a higher risk of developing psychological problems due to the genetic overlap of these issues alone? Just because an observation precedes another and we can logically connect them it doesn’t follow that the first caused the second – “number of books in childhood household” correlates with “adult intelligence” but it doesn’t mean that kids read themselves smart.

The solution is that you need to get a baseline value for your participants on the outcome you think maltreatment makes worse. Maybe maltreated kids are worse off even before they are maltreated, so you need to compare them to that level! There is a nice study which looks at the difference in cognitive performance between maltreated and healthy kids. Being a longitudinal design, it can control for pre-trauma exposure IQ and family SES. If we don’t control for this, we find that in adolescence and adulthood, maltreated kids perform worse. But as it turns out, maltreated kids tend to come from worse off families and have lower IQs even before they are maltreated. Once you control for this, the effect largely vanishes. The figure below is from the Danese review.

Another thing you can do is look at discordant MZ twins. I wrote about similar designs before. Basically, the idea is that you compare MZ twin pairs – same genetics, same rearing family – where one member says they were maltreated and the other says they weren’t. Do the maltreated members fare worse than the other? Two studies say maybe: although most of the association between maltreatment and neurodevelopmental disorders (in this case ADHD and autism) is gone after comparing MZ pairs, a small effect may remain. Remember that these designs can disprove causality but cannot prove it – maybe maltreatment really makes you more hyperactive and autistic, or maybe MZ pair members who have some kind of non-genetic propensity for these problems also get maltreated more (or at least say so). In the end, we got from “trauma scars you for life and this is why people develop mental disorders” to “well, maybe the effect of trauma is not exactly zero”.

Why does the DSM-5 say and why do so many psychologists and psychiatrists believe that suffering from trauma is an important determinant of future mental illness? I think there are several reasons. One is the Freudian tradition which of course was very strongly pro-trauma: at its heart psychoanalysis is about finding hidden, ancient traumas and resolving them. Another is the fact that “trauma causes illness” and “trauma doesn’t cause illness” are just not morally equivalent hypotheses. The second sounds heartless and rude: how dare you question those people who tell you their sad story, and how dare think that this is not why they have a problem? But the world is heartless sometimes, and discovering heartless mechanisms is always a low-hanging fruit in the social sciences, which tend to attract soft-spoken, liberal scientists with excellent crimestop mental mechanisms. So you can make a big bang by showing that people were killing each other in antiquity, that you can tell somebody’s race from X-rays because evolution is real, or that men and women are quite different psychologically, all very true and easy to guess facts but all of which are unthinkable for the modal NYT reader who believes that the world was a hippie drum circle until the Russian hackers released Donald Trump from Hitler’s cryogenic chambers or something. Given how brutal human life was prior to the most recent past, it would be surprising if relatively minor events like seeing our parents divorce or being bullied at school would irreversibly damage us for life.

Another popsci meme bites the dust.

This is an impressive blog! So far I've read two posts and found information I've been unable to locate on my own.

Much though I appreciated this post, I will say that I'm skeptical of the conclusion, though not because I'm particularly credulous about the accuracy of retrospective accounts of past events. Rather, I'm *also* skeptical about the accuracy of official findings. From where I sit in the admitted comfort and safety of my home, neither child protective services, therapy, nor the legal process seem optimized for investigative discovery.

It's also hard to avoid extremely obvious pathways by which negative events would cause some kind of harm: External stress --> cortisol, adrenaline, etc --> behaviors & physiological adaptations optimized for short term survival in a harsh environment. It's one thing to point out that people have an emotional predisposition to presume "trauma is harmful," but people also have a motivation to understand basic causality in the world around them. Denying that trauma has any significant effect leaves us baffled as we consider how the human organism:

1. Goes to such great lengths to avoid psychological pain, even enduring physical discomfort and danger to avoid it,

2. Experiences moral outrage at the sight of traumatic mistreatment of others, and

3. Commits suicide in response to trauma.

Indeed, this last factor gives the clearest evidence that trauma really is damaging; were there many individuals in the above prospective/retrospective studies who were dead at the time the study was carried out?

The obvious conclusion here is straightforward: "there is about a d=0.2, r=0.1 relationship between abused and non-abused college students in terms of mental health, which is statistically significant but not big..." This is the kind of signal one expects from genuine causal factors which may neither be necessary nor sufficient to give rise to an outcome on their own, as Scott Alexander has posted about elsewhere: https://slatestarcodex.com/2015/05/19/beware-summary-statistics/

In other words, r = .1 from trauma is *exactly* what we would expect if trauma really were traumatic, but psychological factors made the difference between overcoming the slings and arrows of outrageous fortune, or being thereby destroyed:

Steel can weather hammer blows, and

Brass endure ages of rust

Willow bends to the howling winds, but

Glass shatters into the dust