As most readers probably guessed, my previous posts on minority stress were the byproduct of my work on an academic paper. This has since been submitted, and although I haven’t got the reviewer reports back, somebody from the editorial office already reached out to me unofficially with some commentary, and I also stumbled upon some additional research. This is nothing groundbreaking, but there are some interesting details.

First, I stumbled upon two twin control studies about suicidal behavior in homosexuals. As you remember, the point of these studies is to try to tease apart causal effects from genetic and between-family factors. If homosexuality exposes you to discrimination and this makes you mentally ill, we should see this effect when comparing people with identical genes and identical families who, however, do not have the same sexual orientation – monozygotic twin pairs where one member is homosexual and one is heterosexual. If we see no such effect – homosexual people usually have worse mental health, but not when we take a sample of them who have a heterosexual identical twin and compare them to each other – we can suspect something like Michael Bailey’s genetic hypothesis wherein there is a set of genes which expose you to both homosexuality and mental health problems.

Anyway, here are the studies.

The first one is ahead of its time, back from 1999: Herrell et al: Sexual Orientation and Suicidality – A Co-Twin Control Study in Adult Men

This study uses the Vietnam Era Twin Registry to identify a little more than 100 twin pairs who sort of match our crazy requirements: one is homosexual (well, technically he said he has had sexual relations with a man since he was 18), and the other is heterosexual (said ‘no’). Of course all are male. “Suicidal behavior” was not actual behavior – only self-reports on thoughts and actions, four types as you will see.

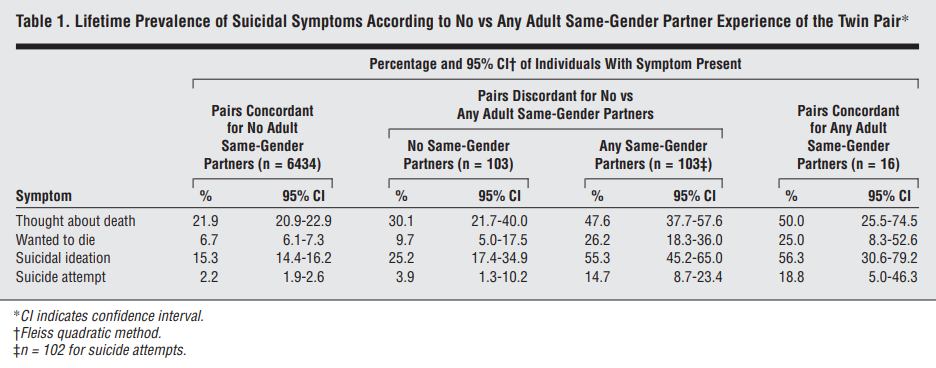

The very informative Table 1:

The pattern you want to look for here is this. All problems are the least common in twin pairs where nobody is homosexual (first column). In pairs discordant for sexual orientation, even the heterosexual member (second column) is doing worse than fully heterosexual twins (first column), but only slightly. The homosexual member in discordant pairs (third column) is much worse off than the heterosexual one (second column), and actually as bad or almost as bad as the members of the 16 twin pairs where both members were homosexual. This means that having a homosexual twin is a risk factor for suicidality even if you are heterosexual, indicating a genetic overlap between the two problems. But it is less sure if having a heterosexual twin member is protective against these problems if you are homosexual as almost the full heterosexual-homosexual difference exists even within pairs, which speaks against these effects. And indeed, these are the within-pair comparisons:

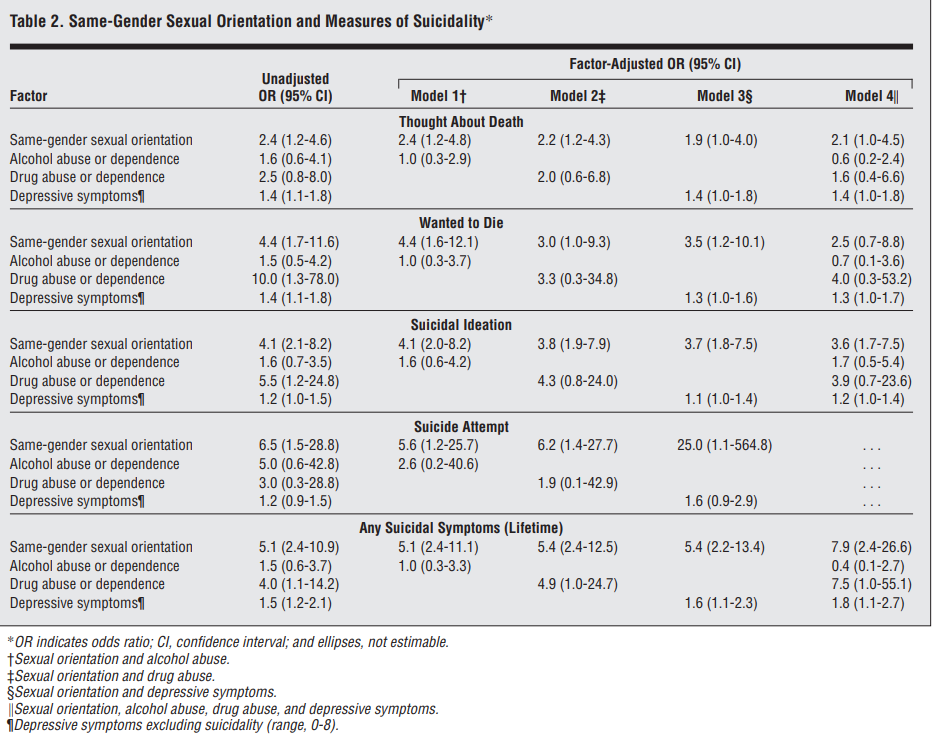

It is the first effect size (unadjusted OR for Same-sex sexual orientation) in each section you are the most interested in: all are really big and significant, showing that being homosexual increases the odds of you being more suicidal than your heterosexual twin pair by 2.4-6.5, a huge difference which is statistically significant even in this smallish sample (N=103). The authors control for psychiatric problems (alcohol or drug problems and depression), which are basically mediating effects: if the association between homosexuality and suicidality went away when controlling for these, it would suggest that while homosexuals twins are indeed more suicidal than their heterosexual pairs, this is because they are more depressed or have more substance abuse problems. This wouldn’t make the original association less interesting, but it’s not even really the case here, the ORs don’t move that much.

Now, a big limitation about this study is that they just compare “twin pairs” without regard for zygosity. This leaves free genetic variance within (some) twin pairs: maybe it’s just that the genetically more at risk members of twin pairs tend to be both homosexual and suicidal. The authors only mention in passing that they tested for an interaction effect and found nothing, the patterns were the same in MZ as in DZ pairs, but there is obviously a power issue with that, this is a small sample. It would be nice to see the MZ effects. The reason I don’t dismiss this paper on these grounds is that the raw data just doesn’t suggest to me that this is wrong. Even if all pairs were DZ twins – given that they are all same-sex, I think only about a third are – you should see the effect of throwing out 50% of genetic variance in the within-pair models. In this case, heterosexuals with a homosexual twin member should be a lot more and homosexuals with a heterosexual twin member a lot less problematic than those in twin pairs where both members match their orientation. The fact that the prevalences reported in Table 1 are so similar between columns 1 and 2 and 3 and 4 tell me that the authors’ interpretation is largely correct.

Also, it is a shame they treated the four suicide measures separately: it would have been nice to construct a suicidality latent factor. But this is just because I’m used to 2020s social sciences, 1999 was a different time.

The other paper: O’Reilly et al: Sexual orientation and adolescent suicide attempt and self-harm: a co-twin control study

A much newer study from 2020. It uses data from a huge Swedish registry, with sexual orientation data reported at age 15 and a self-report on suicide attempts and self-harm at age 18. It is actually a relatively fine-grained report which is dichotomized as “never did this” (about 73% for self-harm, 95% for suicide) or “ever did this”. Non-heterosexual minority status is also pooled across categories, about 88% are heterosexual, 6% didn’t want to answer, 3% was bisexual and 2% homosexual, no unusual numbers anywhere. 302 pairs were discordant for orientation and self-harm and 171 pairs for orientation and suicide – this is buried in the supplement, but it actually a good number!

These are their findings:

In the full sample, non-heterosexuals were about twice as likely to self-harm as heterosexuals. This was reduced when comparing twin pair members: homosexual twins had about 60% greater odds for self-harm than their heterosexual pairs. Adjusting for psychopathology – basically seeing if homosexuals are more problematic because they report more psychopathological problems – didn’t do very much to the results. The confidence intervals are wide of course, even in such a huge sample there are only a few twin pairs where one member is heterosexual and the other isn’t, AND also one reported self-harm and the other isn’t – not that many adolescents are homosexual and thankfully not that many are suicidal either. But all are significant. Interestingly, adolescents who didn’t want to say who they are attracted to weren’t more problematic than the reference.

Now, these are all “twin controls”, but not “MZ twin controls”: there is free genetic variance so we didn’t really exclude genetic effects here! It is suspect that there are some because just by looking at any type of “twin pairs” instead of the general population, the sexual orientation-related risk of problems drops by about 40%. But this study actually does a proper MZ twin control: the effect sizes, if anything, increase (still about 2x the odds), but because there are fewer such twin pairs, this effect becomes insignificant.

Why are these studies important? They are because it would totally falsify the minority stress hypothesis if in within-pair comparisons homosexual MZ twins wouldn’t have more problems than their siblings. According to the theory, being a homosexual exposes you to discrimination and stress, and this is what makes you have psychiatric problems. The opposite – persistent homosexual-heterosexual differences even in MZ twin pairs – can be explained with many things, including minority stress theory.

Two previous studies – which I a lot about in my upcoming paper, so no detailed discussion here – used a much better method: they estimated genetic and environmental correlations between homosexuality and mental health problems. A twin pair comparison – even an MZ twin pair comparison – is basically a primitive version of this, which gives a yes/no answer about whether some of the genetic effects and the nonshared environmental effects (in DZ and DZ+MZ comparisons), or just the nonshared environmental effects (in MZ comparisons) overlap between two traits. One found that the relationship between homosexuality and the neuroticism and psychoticism personality traits is fully explained by genetic factors: basically, we wouldn’t expect a difference in these pathological traits in MZ pairs discordant for sexual orientation, ruling out the idea that minority stress causes them. The other found that for depression, this is mostly but not totally true: the nonshared environmental correlation between sexual orientation and depression is a statistically significant 0.2, suggesting that even in MZ pairs we would expect the homosexual one to be more depressed.

These new studies have a lot of issues with power and the lack of proper MZ comparisons, but their answer to how much of the risk of suicidality in homosexuals is due to genetic factors is – surprisingly – somewhere between “some” and “none of it”.

Twin control studies have the power to totally discredit minority stress theory, but they don’t do that. The best interpretation of the results of these studies is that there is something highly environmental – not shared even by their identical twins – about sexual minorities that predispose them not to neuroticism and psychoticism, but to some degree to depression and to a large degree to suicidal behavior.

Three further discordant MZ studies of sexual orientation and mental health outcomes here:

https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/psychological-medicine/article/minority-stressors-rumination-and-psychological-distress-in-monozygotic-twins-discordant-for-sexual-minority-status/DF3DD4762FF83D7B26C36AE325279020

https://ajph.aphapublications.org/doi/full/10.2105/AJPH.2016.303573

https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/psychological-medicine/article/psychiatric-morbidity-associated-with-samesex-sexual-behaviour-influence-of-minority-stress-and-familial-factors/72656B3B344FE385B58B741CFA0DCD59

Also this sibling-control design study:

https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10654-018-0411-y

Finally, these studies also rule out correlated genetic factors using causal modelling in twin cohorts, so a powerful design:

https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10508-022-02455-9

https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10519-022-10130-x

Genetic correlations could reflect vertical pleitropy. Also in those Zietsch et al studies, aren't the phenotypic (purely behavioral ones say) between sexuality and the mental outcome very small? So even if genetics is explaining all of those otherwise small phenotypic correlations. Not sure how strong evidence genetic correlations are against minority stress mechanisms (that is, do they really rule out purely "psychosocial" minority stress mechanisms since doesn't minority stress theory predict a genetic corelations anyways? Not dispositive evidence either way). Interesting debate though, thanks.