TL;DR: the so-called sibling fixed effect studies are great tools to demonstrate causality in human research, but they are really sample hungry due to how they work. While there are many negative findings with this design, there is a tendency for effect sizes to be in the same direction within-family as in the total sample, which tentatively suggests that small causal effects are real and even the largest studies are underpowered.

With this post I want to highlight a major issue in the research of familial confounding. To recap, the basic problem here is that correlations between exposures and outcomes in the population can have genetic, between-family environmental or within-family environmental causes. For example, poorer people commit more crimes just about everywhere. This might be because people with a certain genetic makeup may be prone to behaviors (e.g. impulsivity) which lead to both crime and poverty – this is a genetic cause. Or it might be because poor people grew up in families which made them both poor and antisocial – this is a between-family environmental cause. A typical sociologist would probably just say that it is poverty itself that causes crime – this is a within-family cause (called so because you would expect that even with the same genes and coming from the same family you would commit more crimes if you are exposed to poverty, that being the actual cause).

The standard design to tell which is which is to compare family members in order to get between-family effects and/or genes (‘familial confounds’) out of the picture. You need to check if family members discordant for the exposure are also discordant for the outcome in a systematic way – for example, if among MZ twin pairs with different incomes where one is a criminal and another isn’t, the poorer one tends to be the criminal one. All familial confounds are out of the picture if you compare MZ twins (as they share both genes and families) so if you see nothing when comparing MZ twins the cause is familial and indirect. Normally you can only study adult exposures – such as adult income – because kids growing up in the same family naturally share many childhood exposures of interest (for example, parental SES or residence). But you can even study the latter with some fancier designs, for example, by comparing MZ twins reared apart or kids whose family moved or had large income changes, so siblings were exposed to residence/income levels for a different time. In a standard adult twin sample you can ask: ‘if I take two people with the same genes from the same family, is the poorer one systematically more criminal?’ This would imply that poverty indeed causes crime (although technically there can still be within-family confounders, that is, real non-shared environmental effects). In a fancier sample, you can ask: ‘if one brother was born in the big city and lived there for 5 years, then the family moved to the countryside and the other brother was born, are there any changes in their mental health?’ This would imply that living in a different type of residence causally affects mental health. “Imply” in both causes because there is still ammunition against this in both cases, but in any case, a negative finding would rule out direct, within-family effects.

Most studies of this type report little or no effect (bringing much joy to hereditarians) in within-family analyses but actually they are rather underpowered, in spite of reporting impressive Ns in their abstracts. This is because the meaningful part of the sample – siblings/twins discordant for BOTH outcome and exposure – are rare. It is rare to have a sibling pair where one ends up a criminal and the other doesn’t AND they saw very different family income levels over their childhood, or an MZ twin pair where only one went to college and only one developed schizophrenia. So usually the actual analytical sample is a few hundred people at best.

If within-family effects were truly zero, the effect sizes – regardless of significance – would be expected to fluctuate around 0. I don’t think this is the case. In many twin or sibling fixed effect studies the effect sizes are systematically higher or lower than zero, even if they never reach significance so the authors conclude that there is no effect. Below are a few examples (with some genuinely negative findings).

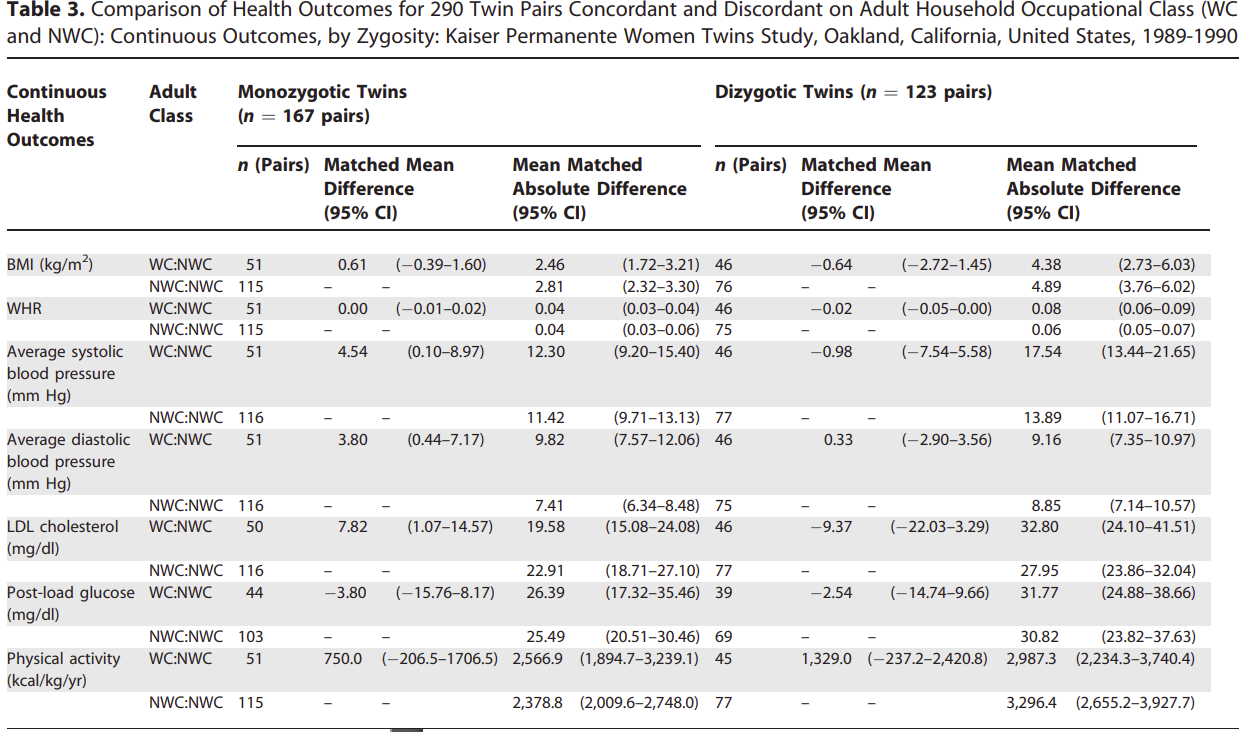

This is a study with a positive finding. There are several statistically significant differences in health outcomes between working class and non-working class MZs, even though the sample size is only ~51. Even the other metrics tend to go in this direction.

But there are not really any differences in relation to having at least 4 years of college education. This is admittedly an imperfect measure of being “educated” and the sample is small, but the effect sizes really are small with no clear tendency.

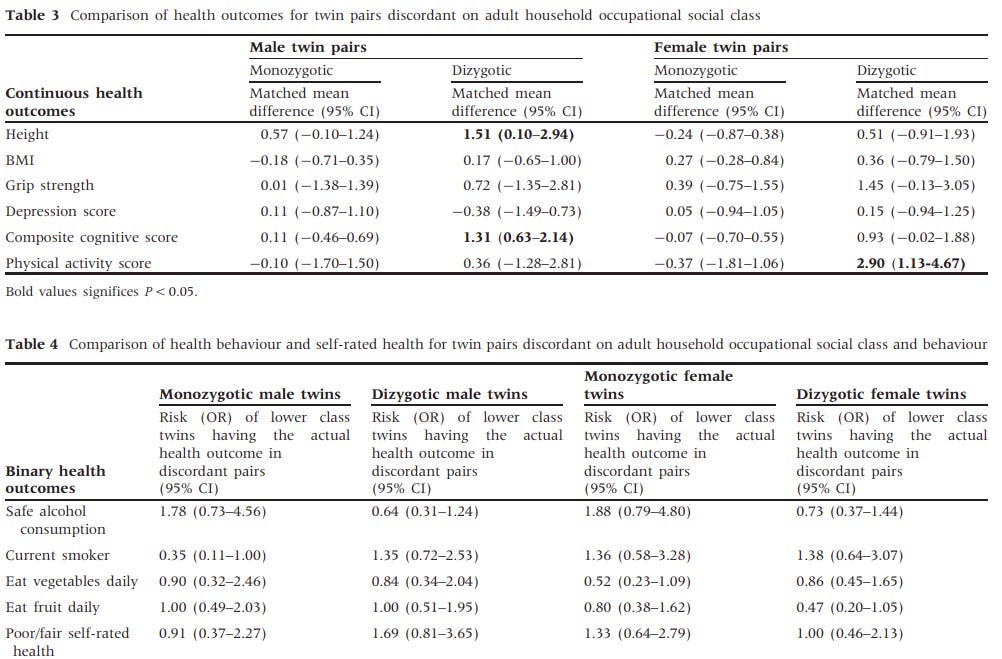

This is a study of MZ/DZ twins discordant on adult socioeconomic status and self-reported/measured health. Authors interpret this as a negative finding and I tend to agree. Confidence intervals are wide and I don’t think it was a good idea to split the sample by sex, but there are 10/22 negative signs or <1 ORs for MZ twins versus 6/22 for DZ twins which is broadly in line with the full population relationship being mostly due to genetic effects. The results look even better if you only consider the objective measures (first table), here there are 5/12 negative signs for MZs but only one for DZs.

Fujiwara 2009 - Is education causally related to better health? A twin fixed-effect study in the USA

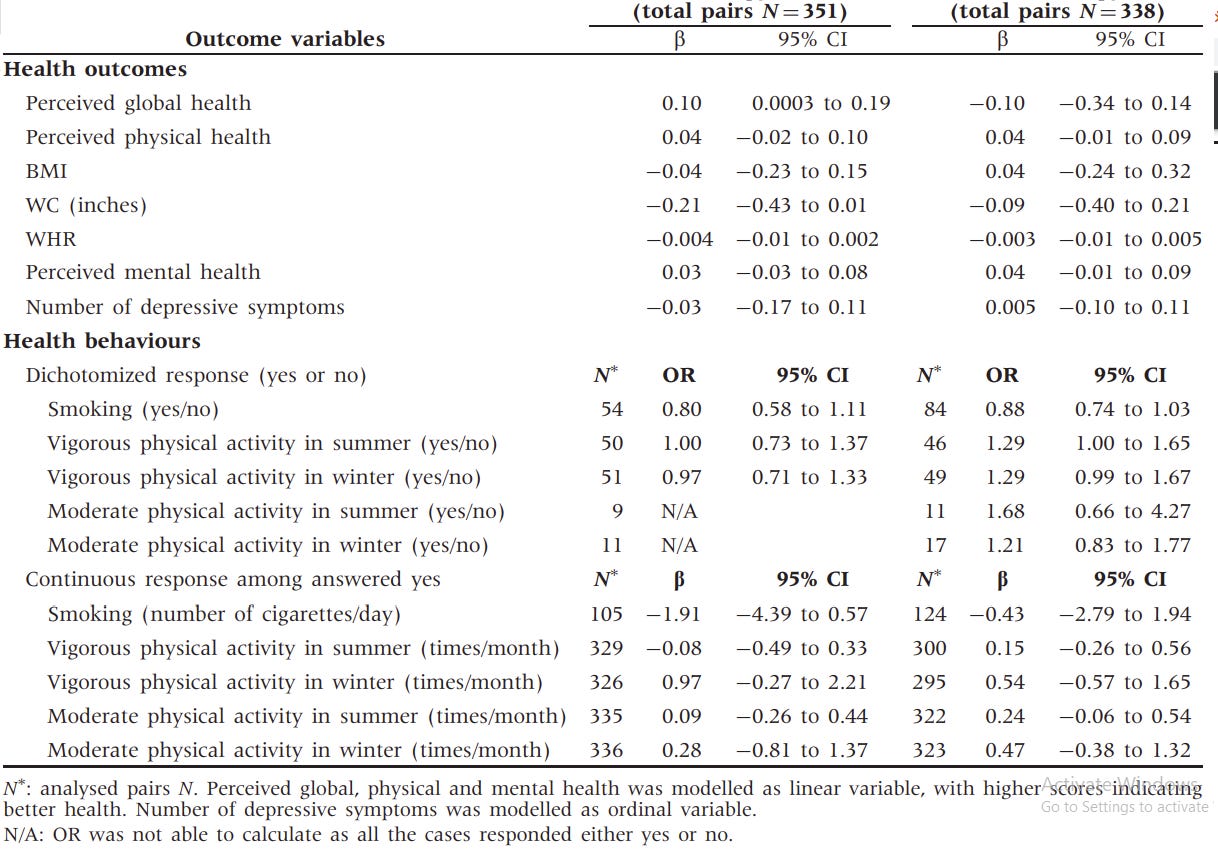

Another American study, participants were discordant for educational attainment (measured by imputed years in education). There are lots of models to run here and the sample is small so nothing is really significant, but I agree with the authors that “the point estimates of the effect of education in the fixed effect analyses suggested a weak protective association”. For example, even in the MZ fixed effects comparison literally every single health outcome effect size is in the same direction we would expect it (7/7) although none of them are significant.

Hamdi et al 2016 - Does Education Lower Allostatic Load? A Co-twin Control Study

This is a major troll study! A keystone of standard sociological explanation for poor health in low SES is allostatic load (the physiological response to chronic stress). If you are poor or uneducated, you have a lot of stress in your life and this makes you sick. Not according to this American study: fancy blood-derived stress biomarkers really vary as a function of educational attainment, but not within twin pairs. The sample is small but the effect really is a hard zero. It is also interesting that the effect goes away even in DZ pairs, which I guess could indicate C effects or strong assortative mating for stress reactivity, but I don’t really have anything to back this up.

This is pretty much the definitive SES vs mortality study so far, with a starting sample size of 40 thousand Swedish people born before 1935 (so plenty of mortality data to analyze). Participants can be discordant for adult education or social class (both categorized). The sample is boosted by an analysis of MZ twins reared apart in families with varying SES. Confidence intervals are still pretty wide but there is a pretty clear gradient in mortality from the highest to the lowest SES categories, even in MZ controls. This is especially true in the lowest category – SES effects appear to be non-linear. Note that every single HR is >1 for Education and again every single one for the first two Social class categories. All MZ reared apart HRs are also >1. Despite the mostly non-significant effect sizes, I don’t see how these HRs do not suggest that growing up in a better family really was protective against dying early in 20th century Sweden, genetics aside.

In these studies it is not trivial though when/where they were done. SES may have different effects in different ages and countries, because it can mean a lot of things to be poor and/or uneducated (or however else you want to define SES). In some places and times being poor (e.g. contemporary Scandinavia) is an inconvenience at most and there is a lot of support available, but in other settings (e.g. the US, Eastern Europe) if you are from a higher social class you can get access to a lot of materially higher quality goods which are not available for everyone, for example, a cleaner living environment or better health care if you are sick. Tellingly, while this sample comes from Sweden, a very well educated country today, about two thirds of all participants fell had only elementary education and social class (actually occupation, unskilled or low-level non-manual).

A classic. This is a sibling comparison study. What happened here is that the author looked at families who had 1) a change in their socioeconomic status 2) had kids born during this time 3) when they grew up, some of these kids become drug users and criminals and some didn’t. The question is: coming from the same family, did the kids who were exposed to poverty for a longer time (for example, because they were already alive when the parents were unemployed while their younger brothers were born just before they eventually got good jobs) systematically more criminal or more drug-addled when they grew up?

The poverty-drugs/crime association definitely holds up in the entire population. Look at Model I: for example, the poorest kids (Quintile 1) are about seven times as likely to be criminals and 2.5 times as likely to be drug users as the richest kids (Quintile 5). But look at the HRs in Models IV (sibling fixed effects, this is where the design I described before is actually done). For violent crime, they are less then one, so the effect is negative. If anything, once you get confounders out of the picture and compare siblings, those growing up experiencing more income than their brothers/sisters tend to be MORE criminal! But for substance misuse, they are positive and not even much smaller than in the total population (Model I), except for the lowest category.

Finnish replication. Look at the point estimates – all are <1, just like in the total population. OK, most of them are really, really trivial. Somewhat different for substance use. Maybe poverty does cause a small risk of this outcome (the rate is ~+1%/1000 Euros per year if I understand correctly), but you can’t even detect it reliably in a national population sample.

But the authors break these down by age at which family income is calculated and then even the trends disappear. I’m not sure how to interpret this. I also don’t understand how the confidence intervals are smaller for ages 10 and 15 than for the averages.

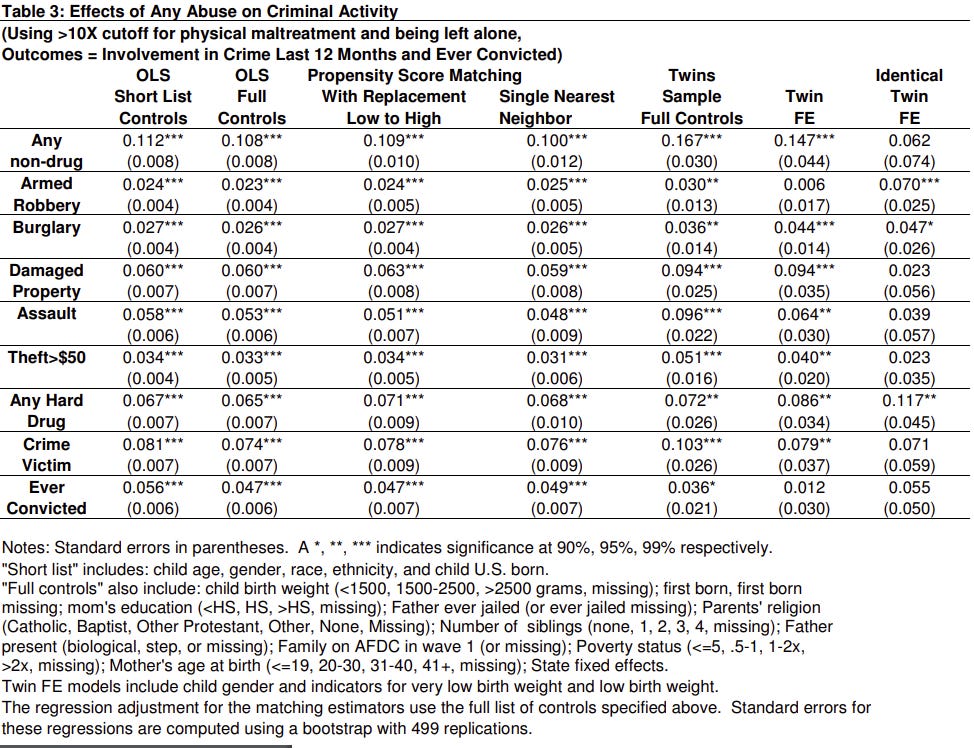

Currie & Tekin 2007 - Does Child Abuse Cause Crime?

This is an economist paper with Add Health twin data. The exposure is self-reported abuse and the outcome is crime based on administrative data. The authors worry more about the math then the design and while they do “twin fixed effects” they only use the proper MZ fixed effects once. The results are below. While they explain a lot into this, the results are not that impressive, only armed robbery has a semi-believable <0.01 p-value in the MZ fixed model. But note that 1) all coefficients are positive and 2) not that different from ordinary twin fixed effects models.

Retrospective self-report measures of abuse are notoriously unreliable so I’m not sure if we can conclude that “abuse causes criminality”. But I don’t see how we can dismiss these effects as totally negative. Maybe it’s just that people who committed crimes are more BPD/psychopathic regardless of genetics and more likely to complain about abuse, but there IS something here.

Two similar studies:

Dimwiddie 2000 - Early sexual abuse and lifetime psychopathology: A co-twin–control study

Nelson 2002 - Association Between Self-reported Childhood Sexual Abuse and Adverse Psychosocial Outcomes

All checked if co-twins who reported childhood sexual abuse (CSA) have worse mental health.

Dinwiddie:

Nelson:

Report rates are high, 6% of women and 2.5% of men in Dinwiddie and almost 16.7% of women and 5.4% of men. Because of the low rates of men, discordant pairs are rare. I don’t think these results should be taken at face value either (these abuse reports are not reliable) but there is definitely something here. All ORs are positive, even though the CIs are huge and neither effect is significant in Dinwiddie. People who report CSA also report other problems, and this is not just genetics! A telling example of what is going on, however, I think is the case of OR for rape in Nelson. You could come up with a causal explanation for other outcomes (“the trauma from CSA increases the risk of suicide/depression”) but why would being abused as a child increase your chance of being raped? Correlated biases in the reports are IMO a better explanation.

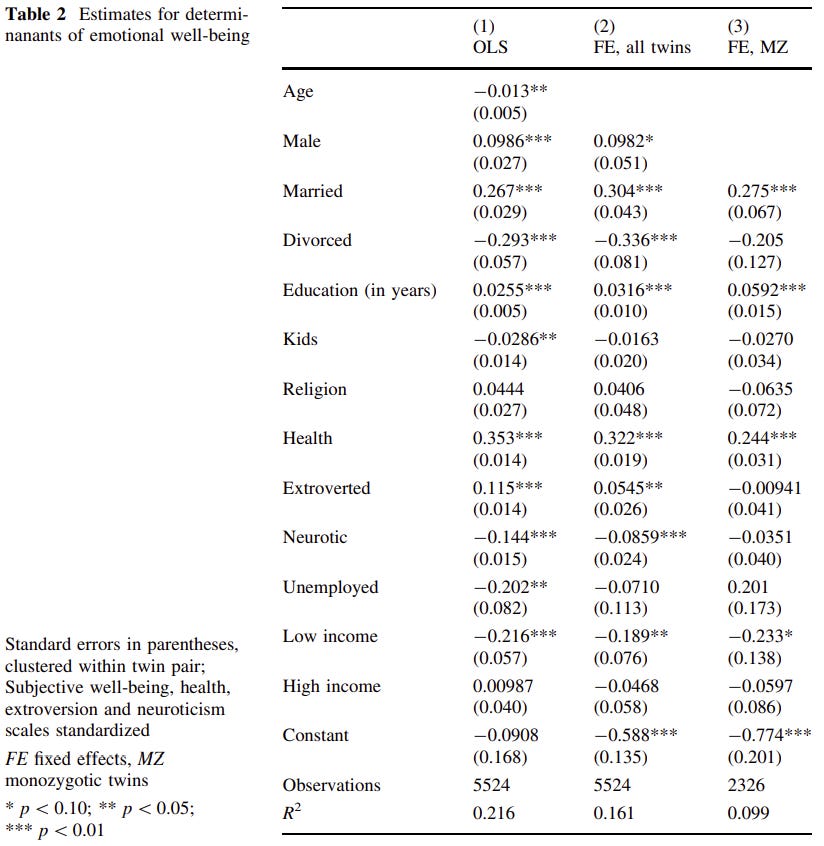

Finally, an interesting paper on self-reports: Misheva 2016 – What Determines Emotional Well-Being? The Role of Adverse Experiences: Evidence Using Twin Data

There are quite many Australian twins in this sample. Self-reports of happiness are related to things similar in MZ comparisons than in the general sample. Being married and better educated, reporting good health improved but low income reduced happiness.

Population effects of traumatic events go away in MZ comparisons (but the effect sizes are mostly retained, this is mostly a power issue!) but a cool thing the authors do is that they separate recent traumas (<1 year) from older ones. That way, recent traumas seem to affect happiness reports even in MZs but older traumas don’t.

There are probably very real environmental effects on self-reports!