How wokeness killed both intelligence journals, and why g is real

A sad special issue in The Journal of Intelligence, and Process Overlap Theory

There used to be roughly two scientific journals dedicated to intelligence research: Elsevier’s Intelligence and MDPI’s Journal of Intelligence. Intelligence was the older one which survived many scandals and published pretty based papers until recently. However, Elsevier recently decided to gut the journal, dismiss the veteran editor-in-chief and replace him with some unknown Romanian man. Aporia Magazine covered the story.

Journal of Intelligence is going down a similar path. This journal recently published a special issue called “Assessment of Human Intelligence—State of the Art in the 2020s”. One could write a lot about state of the art intelligence measurement: for example, short intelligence proxies which can be used in very large samples, the open-source ICAR-test or adaptive intelligence testing. Unfortunately, there is very little of this technical state-of-the-art in this issue and much more about political state-of-the-art which suggests nothing good about the future of this journal either.

Right in the editorial they start by denouncing Lewis Terman and Henry Goddard, fathers of the field, as “despicable” and “devotees of Spearman’s g theory” in contrast to Binet, Simon and to some extent Wechsler who „believed neither in g nor fixed intelligence”. They also assert that “society and the scholars in the field have moved on from eugenics, g theory, and fixed intelligence, the landscape of modern assessment has moved toward a framework that is more equitable and socially just in concert with a society that increasingly emphasizes the importance of diverse viewpoints”.

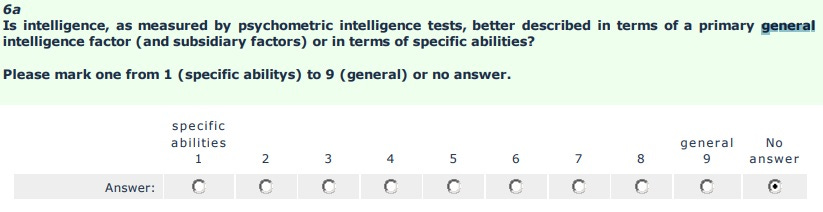

This statement, by the way, is a lie. In the most recent anonymous intelligence expert survey, Rindermann et al asked researchers pretty direct questions about these issues. About the g-factor, responding to a question like this:

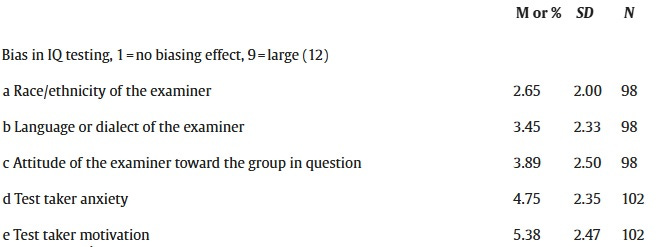

the mean response was 6.84, so the average expert believed the g-factor is a pretty good explanation of test performance. They asked indirectly about the ordinary, within-group type of heritability but I can’t find it in the results. However, since they even estimated the thornier Black-White differences to be ~50% genetic, the mean researcher is probably quite a hereditarian, which would imply both a belief in “fixed intelligence” and “eugenics” to some degree – if something is heritable, you could expect it to be relatively stable and breedable. They strongly disagree that IQ tests need to be more “equitable” or “socially just”, because they judge the tests to be relatively unbiased, especially against ethnic groups, and they disagree that separate norms are needed:

It’s bad news that the editorial is like this, but the issue is actually not that inflammatory, except for one paper by LaTasha R. Holden and Gabriel J. Tanenbaum, with the title “Modern Assessments of Intelligence Must Be Fair and Equitable”. This paper is worth some analysis, which was my main goal writing this post, because it’s full of ideas one can expect to be central in the new, woke intelligence research these journals plan on doing from now.

From the abstract:

“First, we highlight the array of diversity, equity, and inclusion concerns in assessment practices and discuss strategies for addressing them. Next, we define a modern, non-g, emergent view of intelligence using the process overlap theory and argue for its use in improving equitable practices. We then review the empirical evidence, focusing on sub-measures of g to highlight the utility of non-g, emergent models in promoting equity and fairness. We conclude with suggestions for researchers and practitioners.”

To call for DEI in assessment – that is, the measurement of differences – is odd to say the least. I guess one can claim that trans women of color either have some unique ability they can use on the board of Boeing, or they deserve the board position as a handout to compensate for past injustice. But psychometric tests by definition need to be standardized (that is, non-diverse), result in different scores in different people (that is, non-equitable) and inform some judgement based on these scores (that is, non-inclusive). A test which everybody can take in their own way, gives everyone the same score or doesn’t allow judgements about things like university or job admissions is useless.

The paper repeatedly calls for abandoning g theory and adopting alternative theories, such as Kovács & Conway’s Process Overlap Theory (POT), to achieve DEI:

“We argue that non-g POT is a better model due to it being more parsimonious (see McGrew et al. 2023), being better for equity, and because it shows us where to focus when we consider forms of cognitive optimization or enhancement through intervention.”

“non-g POT is also better for working toward equity and fairness goals.”

“Overall, developers of cognitive assessments should be updating their current practices to be fairer and more equitable for diverse groups. Part of this approach should include thoughtful examination of the theoretical bases of these assessments and shifting to non-g models of intelligence such as POT.”

It’s easy to see why this line of reasoning is attractive. Race differences in intelligence imply that there is such a thing as intelligence. If you can make the concept of intelligence disappear, maybe all the race IQ maps and Black test results will stop making sense too. IQ realism arch-nemesis Stephen J. Gould already wrote way back in his 1981 book The Mismeasure of Man that “g is the rotten core of Jensen’s edifice”.

This was a fallacy back then and it is a fallacy now. What happens here is confounding two separate questions: the validity and the structure of intelligence.

It is beyond any doubt that if you get the sum scores of IQ tests – especially if these are nice factor scores, that is, you weigh the points people get for specific exercises by their g-loading before summing – they predict important life outcomes such as education or income. This is validity. Actually, even things which are not nominally IQ tests will function like one, such as the SAT, the ACT, the PISA test, dyscalculia measurements, school grades, short intelligence proxies etc., so once you do any kind of cognitive measurement your baseline assumption should be that you are getting something pretty close to what an IQ test would tell you.

One problem with this can be bias. The test score is just an indicator of what you are trying to measure (cognitive ability). It is like the mercury in a thermometer, which is not temperature itself. Under most circumstances looking a thermometer is a good way to know how hot the weather is, but there can be special cases (e.g. breathing on the thermometer) where it fails. It is theoretically possible that e.g. uneducated people or Black people who have a slightly different culture are not less intelligent, only less familiar with the content of IQ tests, so given a certain level of intelligence they get a lower score than a more educated or White person. This would be bias. Sometimes there is bias against immigrants or African Blacks (but see this), but the tests are unbiased against American Blacks. This issue is so beaten to death that Arthur Jensen already wrote a whole book about it more than 40 years ago. To the extent a psychological test can be “equitable”, an unbiased test already is, and IQ tests are OK by this criterion.

So far, this is a purely statistical phenomenon, it is about prediction: you measure something to know something else. By showing low bias, you shouldn’t even be concerned that your measurement underestimates some people. When it comes to applied psychology – such as testing in schools or university admissions – validity is the end of the line. The SAT is not a scientific experiment, it merely tries to find the students best suited to elite universities.

The structure of intelligence is a completely different question. This is a question not really meant for psychometrics or social science anymore, but for basic laboratory cognitive psychology, neuroscience or even neurology.

g factor theory is based on the positive manifold, the observation that all test performances correlate. People who are better at remembering numbers are also, on average, better at completing matrices, they have faster reaction times, a better vocabulary etc. A g factor – a general intelligence you can use in every test so performance ends up correlating – is one possible explanation for this, but not the only one. Three alternative models from John Protzko’s great paper:

The network model (left) says that there are many independent human abilities that influence each other so they end up correlating. The bonds model in the middle says that not only are there many independent human abilities (bonds, in yellow), but they are even more particular than our language would suggest. An ability is not “reading” but “recognizing a tilted line that can be part of a letter”. Even cognitive tests we think of as very simple tap into many of these elemental “bonds”, so performance ends up correlating basically out of error, like being unable to push a single button on a tiny keyboard because our fingers are too big and clumsy. Process Overlap Theory (POT, on the right), which the DEI authors prefer, assumes that elemental abilities are organized into broad abilities like fluid or verbal intelligence. These are independent, and the only reason they correlate is because they all have to pass through the bottleneck of limited executive functions when we use them. This phenomenon gives rise to g. In all three models, there is no g, except as a statistical artifact.

Arguing that g is not real is like arguing that God exists. It’s not precisely defined just how real g or God has to be for our hypothesis to stand, so we can read whatever we want into the data. A very weak form of the hypothesis is obviously true: you can think of order in the universe as divine by itself, and there is certainly no organ in the human body which creates domain-general intelligence.

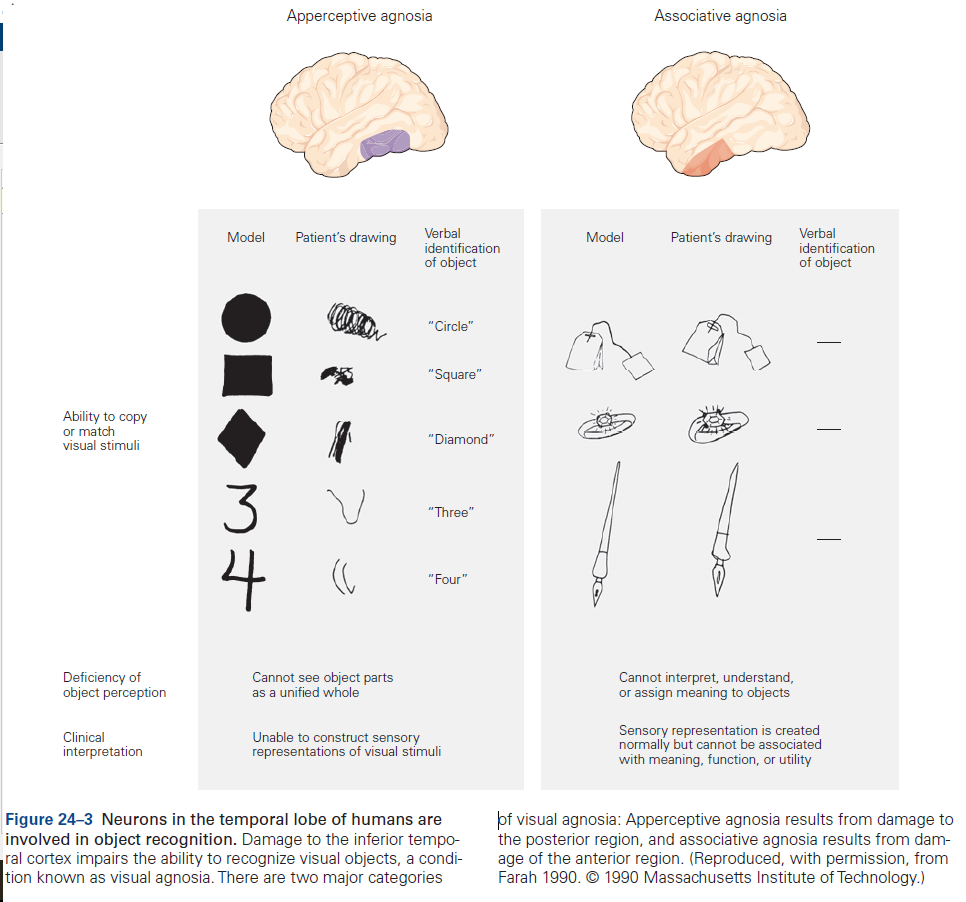

The weak non-g hypothesis is worth considering because on some level, human abilities are obviously modular so g theory in the strictest sense is wrong. If your occipital cortex is injured, you become blind. People with injuries to higher-order areas develop all kinds of strange specific deficits, such as the inability to learn new information (like in the movie Memento), recognize faces, pay attention to the left visual field, or name objects they can otherwise copy just fine.

Weird agnosias in some clinical cases. After brain injury/stroke, these people lost very specific abilities (source: Kandel-Schwarz: Principles of Neural Science).

Research with actual IQ tests and statistical models shows that people with brain injuries have specific, not general deficits. If g was some single ability in the brain, this is not what we would expect. At the most basic level, the brain must consist of networks to support specialized calculations and functions. General intelligence emerges from these modular abilities somehow.

But the stronger the claims of the non-g hypothesis get, the harder they are to defend. Just as there is no man with a white beard sitting on the clouds, there is no way to handwave away g-centric intelligence research with just neuroscience.

Maybe a very strong form of g-theory (that of almost a “g organ”) is untenable, but the alternative theories like network models or process overlap theory don’t stand up to data even in their weak forms. This is because of the very observation I brought up against g itself: injuries (and training effects) remain localized to abilities. This argument was recently made by John Protzko in two papers. Both cognitive training effects (improved abilities) and brain injury effects (impaired abilities) affect specific abilities, not intelligence. If you scroll up the models I showed up, you will see that in all of them the arrows go from lower to higher abilities: general intelligence is a consequence (or rather a “sum”), not a cause of lower-order abilities, so it should be affected by whatever changes to the latter. This is especially bad news for a network model in which training effects and injuries should spread all across the ability spectrum, but POT also struggles to explain localized deficits. (The bonds model can work as long as we believe that all of these injuries affect exactly one bond, but that is a tall order.)

While the brain is organized of specific functions at the most basic level, it’s questionable if we ever interact with the world with these. Maybe by the time we use our cognition for anything real, we are already using the interacting system of elemental functions known as g so that’s the right level of description. This would make non-g theories textbook cases of a Rylean category error: using the wrong level of complexity to describe what we are analyzing. One of Ryle’s examples of this phenomenon is a person being shown a cricket team. After hearing what each player does in the field, he asks which player is responsible for the “team spirit” he heard so much about in cricket. Of all of these brain areas, each performing “visual analysis” or “speech comprehension”, which makes this famous “intelligence”?

To return to a previous point I was making, problems with explaining lesion or training data is not the biggest reason you can’t just use POT or a network model to explain away g effects. The biggest reason is that the structure of intelligence has no relevance for assessment (validity). Whenever you can even think about DEI, the structure of intelligence is irrelevant. This is because assessment is only about information: if we got that information quick and dirty, so be it. Bear with me on this for a little.

In their foundational POT paper, Kovács & Conway contrast formative and reflective interpretations of factors. Look at Uli Schimmack’s illustration below:

In a reflective interpretation, shown on the bottom chart, there is a real latent trait like “intelligence” or “extraversion” floating somewhere in a world of Platonic ideals, unmeasured. In our fallen world, all the measurements we can make come with error, but they still reflect this trait to some degree. We can estimate the unmeasured perfect trait by getting the average estimate of many imperfect measurements: summing up scores, ideally weighted by factor loadings. The core assumption here is that the reason measurements correlate is because they tap into the same thing. G-factor theory makes this assumption, but POT doesn’t.

POT instead assumes the interpretation shown on the top chart, a formative g-factor. Cognitive tests correlate for whatever reason, not because they reflect a real g. We can sum up scores if we want and calculate IQ/g, but it doesn’t automatically mean that “intelligence” is real.

Kovács & Conway bring up socioeconomic status as one example of a formative factor. They say that just because income, education, place of residence etc. are correlated, they do not reflect some unmeasured, Platonic ideal “socioeconomic status” which causes them. Instead, “socioeconomic status” is simply a sum score of all of these things, a handy aggregate of all the social assets we have.

It is true that socioeconomic status is poorly and flexibly defined and its components correlate quite weaky. In this sense, a total SES measure is quick and dirty information. Still, if research showed that socioeconomic status causes things like criminality (validity), then we would have to seriously consider it an important variable in applied psychology. The only way structure mattered is if you claimed that because “total SES” is an arbitrary sum score, more information could be extracted by using its components, such as income or education, as predictors. (This is the very argument Gary Marks makes in the paper I linked above). The IQ analogy would be that because g is just a formative factor, we should use test scores on reasoning, vocabulary etc. tests instead of their aggregate, IQ/g. But this would be false, g contains almost all of the predictive validity of IQ tests. I wrote about this before: I think that whether something is best thought of as a formative or a reflective factor can be decided whether useful information remains in the specific variances (for example, if personality items residualized for the total trait score still predict behavior). By this standard, personality appears formative, but intelligence reflective. Even if you disagree with me, even if POT is the true model of abilities in the brain, even if g is just a quick and dirty sum score of a formative factor, it still contains almost all the information you can use in assessment, just as if g theory was real. We know this because we measured it. If one structural model (g-theory) maximizes validity, that is the end of the line in assessment, even if the actual structure is somehow different. Basically, the more we want non-g theories to inform real-life decisions, the more wrong they get: at some basic neurological level they can be true, but they certainly don’t mean anything like “intelligence doesn’t exist after all so we shouldn’t measure it”.

The fall of both intelligence journals in such a short time is sad, especially now that DEI might be on its way to be rolled back. Maybe process overlap theory to become the PC, cathedral-approved intelligence model for the next few decades, which would result in a lot of wasted time, money and energy.

Just published a follow-up piece that was inspired in large part by this article (and Aporia’s as well). I think your coverage is sharp and much-needed, especially in drawing attention to the institutional rot and ideological pressures at play.

That said, I do think one key piece has been underemphasized: the genetic evidence for g is already strong, and it offers a more parsimonious and empirically grounded explanation than the newer models currently being promoted. I try to expand on that angle a bit more here:

https://open.substack.com/pub/biopolitical/p/the-genetic-reality-of-intelligence

Thanks for helping push this discussion forward.

I have high mathematical specific IQ but my spatial specific IQ is nothing special. I don't believe that substantial variations in specific IQs is rare. A great author or lawyer might be pretty ordinary at math or chess.

Association with Herrnstein and Murray poisoned the two National Longitudinal Studies of Youth so thoroughly that nobody cites the data anymore. Yet they measured the individual on so many different axes that they should be rich sources for comparison.