In the past few years, I became very impressed with the power of propaganda. When I was in school, I saw things like World War 1 recruitment posters, and I didn’t understand how people could volunteer to serve in the trenches after seeing jingoistic cringe like that. Then the 2010s came along and I started hearing people parrot talking points I read almost verbatim on the internet about migrants, rape culture and other politically loaded stuff.

In some cases, the talking points were both extremely radical and completely new: a few years ago I wouldn’t have thought that it is possible to convince the majority in the West that men can really become women, that it is OK to close down society indefinitely due to an epidemic of dubious severity, or that where the borders of some Eastern European country lie is a matter of good and evil. The start of the Ukrainian war was especially brutal: from one day to the other random sites like 9gag were flooded with war memes and I was getting non-stop NATO propaganda in my Windows notifications right next to the clock and the weather. These talking points were obviously centrally manufactured and spread – and they were adopted by enough people to matter.

I think this is interesting outside of politics and my distaste for leftism and Atlanticism (which you don’t have to agree with). It shows the power of words, the fact that sometimes it is possible to change the whole world by just telling people something. I became interested in doing an empirical demonstration of this phenomenon.

Doing word magic deliberately, with a lot of funding and access to the media is called “propaganda” or sometimes “advertising”. Because lots of actors compete to sell you their politics and products, this effort might be hard to trace objectively – too much secrecy, too much noise. So I focused on a less competitive field: fiction. I think there are concepts out there we are all familiar with even without personal experience (like a fictional creature or an interesting thing nobody really does but everybody fantasies about), which were introduced by a single wave of the word magic wand. I don’t mean something like wookies or lightsabers: everybody knows those, but we also recognize them as fictional ideas specific to the Star Wars universe. I’m looking for very mainstream concepts whose origin in a single piece of fiction is not even widely known to people who aren’t art nerds. Propaganda works best when we don’t notice it.

After dredging my memory, talking to friends and asking ChatGPT, I came up with the following list things that were: 1) once unknown or marginal concepts, 2) now they are widely known, 3) their fame could be reasonable traced back to a single publication:

- Bodybuilding: a fringe fad since the 19th century and rarely called by its modern name, bodybuilding became mainstream after the 1977 Arnold Schwarzenegger movie Pumping Iron.

- Breakdancing/rap music/hip hop: already huge in the 80s, but apparently the first hip-hop album that kickstarted this culture was “Rapper’s delight” by Sugarhill Gang in 1979.

- Extraterrestrials/Martians/alien invasion: H. G. Wells wrote War of the Worlds in 1898, which was featured in the famous radio play by Orson Welles which convinced many listeners that the aliens were actually invading. In 1951, the alien invasion movie The Day the Earth Stood Still came out, popularizing the same concept.

- Kung fu/martial arts. The first works of fiction popularizing Eastern martial arts in the West were the series Kung fu (with David Carradine, 1972-1975) and Bruce Lee’s Enter the Dragon in 1973. I chose the latter as my reference year.

- The Mafia. Organized crime has a long tradition in both Italy and among Italian Americans, but it wasn’t that well known until The Godfather came out in 1972.

- Skateboarding. This was a very fringe hobby in the 1980s. There was a magazine called Thrasher in the early 80s, but skateboarding really became popular after a documentary called Thrasin’ came out in 1986.

- Surfing. Surfing is traditional in Polynesia and it was a local hobby in California until the 1950s. A novel about a surfer girl called Gidget was published in 1957 and a movie version came out in 1959. ChatGPT also suggested an 1966 movie called Endless Summer as a factor in making surfing well-known so I added it to my list.

- Time Travel. H. G. Wells published another concept-making novel, The Time Machine in 1895. In the more modern era, I guess Dr. Who (1963) and Back to the Future (1985) were important in making it popular.

- Vampires. Bram Stoker published Dracula in 1897. In the more modern era, book adaptation movie Interview with the vampire (1994), Buffy the vampire slayer (1997) and the novel Twilight (2005) were important in popularizing vampires.

- Superheroes. Superhero comics had been relatively popular for decades but Superman: The movie in 1971 made the concept much more mainstream. The first superhero movie of the current Marvel series, Iron man, was released in 2008.

- Yoga. A ChatGPT idea, Yoga apparently went into the mainstream after the publication of the 1960 book Complete Illustrated Book of Yoga.

Some of the candidates are better than others, but my hypothesis was not that every work I can think of will influence popular discourse but that there are a few that do. It’s a “some swans are black” type of phenomenon, it’s a big deal if there any mainstream concepts out there which were introduced by a single piece of work, especially if the source today is not even widely known. It would be a powerful demonstration that, at least in some cases, it is possible to change popular consciousness purely through art.

I measured “interest” with word frequencies in print publications, tracked by Google Ngram, which is appropriate for our timeline which mostly pre-dates the internet era. I used the ngramr R package to extract word frequencies, my code is here. It needs an xlsx document with the words, to which you can add your own.

I always extracted word frequencies 10 years before and after the publication of a critical work. I transformed these to percentages relative to the year before publication. I also added a sort of treatment variable, coding each year as 0 if it was before the publication of a work and 1 if during or after. I always fitted a piecewise regression model with this formula:

Frequency ~ Year + Treatment + Year*Treatment

“Year” captures the linear time trend. Maybe interest in a concept increases or decreases over time anyway when a critical work is published. “Treatment” captures the additional effect of the publication of our work. A significant effect shows that, in addition to the normal time trend, interest was increased after a critical work was published. The most interesting effect is the Year*Treatment interaction. If this is significant, that shows that after a work was published, trends in interest changed: for example, after a long time of flatlining interest people suddenly wanted more and more “vampires” or “hip-hop” each year after somebody’s work showed these concepts to them.

Word magic is real

As it turns out, my intuition was right and Ngram word frequency trends go way up after the publication of many of my candidate works. Let’s see an example, “bodybuilding” word frequencies before and after “Pumping Iron” (1977):

Before this work was published, “bodybuilding” was sometimes, but increasingly rarely mentioned in printed text. Maybe there was a small rebound in interest immediately before “Pumping Iron”, a phenomenon we will often see. Immediately the next year, 1978, “bodybuilding” is at a 10-years record high interest in print publication and interest skyrockets for the entire 10-year monitoring period. Both the publication main effects (=higher word frequency after the movie than long-term trends would predict) and the interaction (=change in frequency trends after the movie) are highly significant.

Today, just about every guy goes to the gym but few even know about Pumping Iron. Arnold Schwarzenegger was a magician who conjured his fringe hobby into mainstream consciousness.

These are the plots for all my candidates:

In many cases, including many where the candidate work had a previously almost unknown theme, we see the trend we are expecting. After the publication of candidate works introducing a new concept, word frequency in print increases and previous trends are broken. P-values for both publication and interactions with time are highly significant, showing that the publication increased interest in the concept it presents.

Sometimes the trends are not very nice and significance is misleading. For example, for “Interview with the vampire” and “Buffy the vampire slayer” there are no trend breaks after many years later so while the 10-year window makes the model significant, their direct effect is doubtful. Many critical works seem more like a consequence than a cause of a rise in interest in a concept. For example, interest in the mafia, zombies, superheroes and kung fu was already rising when works I thought brought them into the mainstream out of nowhere were published, and looking at the charts it’s dubious they made a difference. In some other cases the significant interaction shows a deceleration and in one case (Dracula - “vampire”) a drop of interest after the publication of a critical work. Still, there are many instances where interest in a previously unknown concept rose meteorically right after a work of fiction was published. Below I will elaborate on some examples.

You can see all the individual plots here, in a way that’s more legible.

Ain’t nothing like hip hop, dummy

Another way to explore these results is to overplot relative changes in word frequency across candidates. I had to create two plots for this because the two hip-hop concepts – “rap music” and “breakdancing” – blow everything else out of the water.

Change in printed word frequencies of “rap music” and “breakdancing” after the 1979 album Rapper’s Delight by Sugarhill Gang

Neither “rap music” or “breakdancing” are ever really mentioned in print before 1979. Ngram frequencies are often a hard zero. 1979 is the year this changes and word frequencies blow up in the 1980s. “Breakdancing” is more of a short-term fad but “rap music” keeps increasing for at least two decades. I looked at longer-term trends and it only starts decreasing in the 2000s, mostly because the alternative term “hip hop” gains popularity. If you are looking for something completely new that was memed into mainstream existence in just a few years in living memory, look no farther than hip-hop. For comparison, the 2010-2019 “Great Awokening” word frequency changes documented by David Rozado – skyrocketing use of terms like “white supremacy” and “misogyny” – are about a magnitude lower, and only “transphobic” (+12346%) compares.

By the way, Ngram tracks relative, not total frequencies. For popular culture concepts – like pretty much all I’m looking at here – these tend to constantly go up over the 20th century, so these long-term increasing trends of hip-hop culture concepts are not an anomaly. I think that as time went on, printed texts were increasingly about fiction and entertainment and less about serious matters.

Movies are a better medium but “Gidget” is the most magical book

At least on my list. The fact that you never heard about it makes it even more magical.

Let’s look at the chart below:

Change in printed word frequencies of all other concepts after the publication of candidate works.

These show word frequency changes over time relative to the publication of each candidate work. The position of the labels on the right basically tells you how successful each work was in introducing its subject matter to the mainstream. Typical 100-year word frequency changes are around +250%, which is easily the magnitude David Rozado recorded about Great Awokening terms. “Zombies” or “time travel” blew up in the mainstream after the publication of my candidate works about as much as “sexism” or “racist” over the course of the 2010s.

At the bottom you find four classic books and two movies/series of dubious originality (“Endless Summer” about surfing and “Dr Who” about time travel). As word magic exercises, classic fiction books like “Dracula” or “The Time Machine” were flops. Although extremely novel ideas, people weren’t more interested in vampires and time machines after their publication. The yoga book also flopped by this metric. For “skateboarding”, we can compare the print magazine with the documentary published a few years after and see the difference. I think motion picture is just a better medium for spreading word magic.

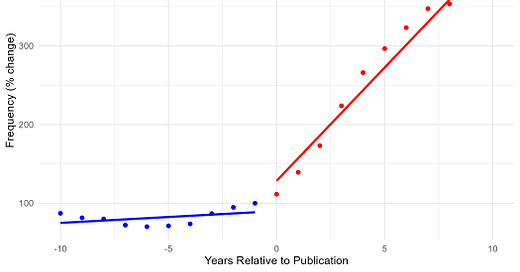

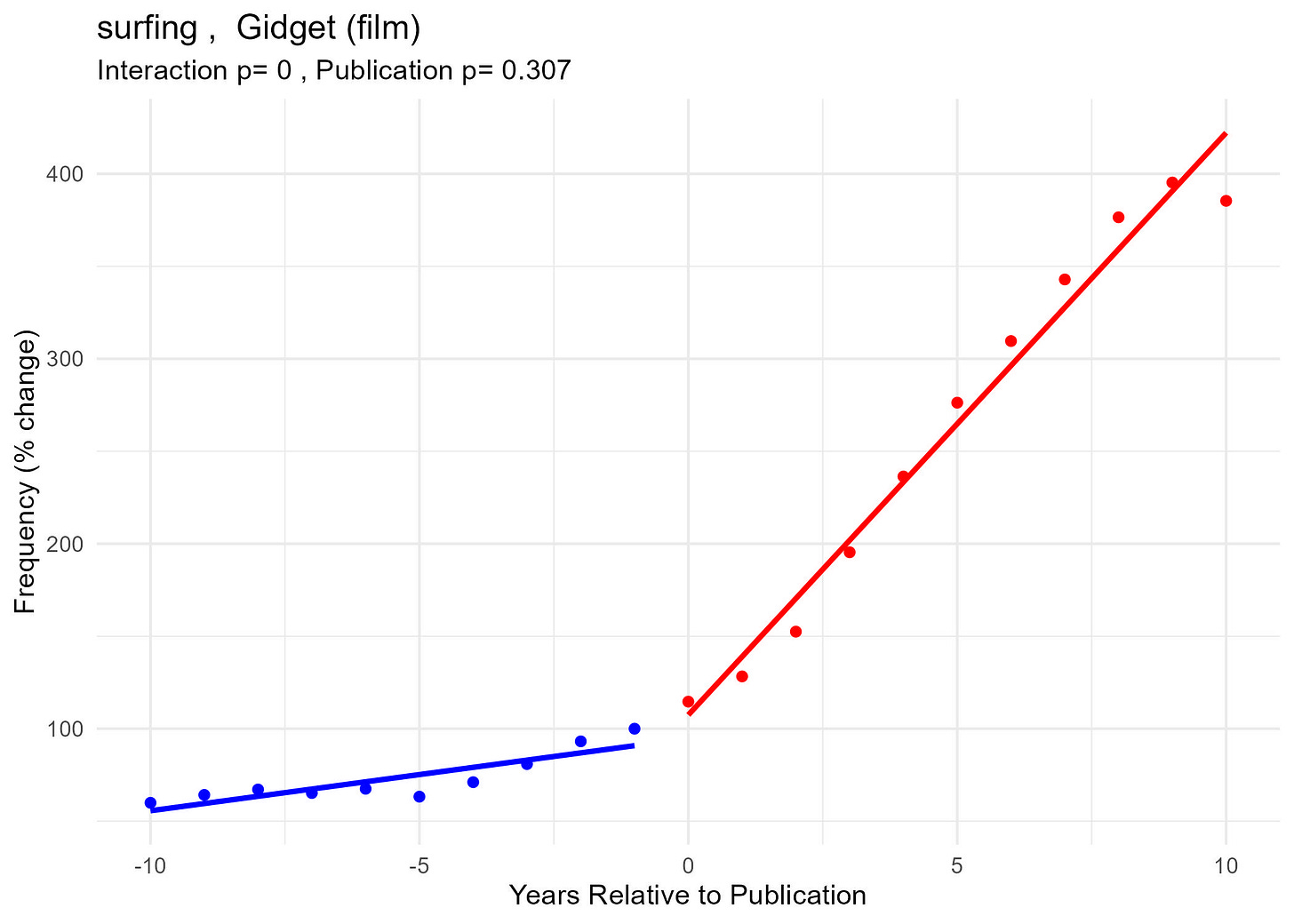

Still there is one hugely successful book on the list: Gidget, a novel about a surfer girl published in 1957. I never heard about it before writing this post. Here is the word frequency plot of its movie adaptation, published two years after:

I think the trend break comes not really where the red dots start, but two dots earlier: that’s when the book came out. Even if you disagree with my visual overfitting to single datapoints, Gidget the movie was based on Gidget the book, so the latter can, I think, still be credited with introducing “surfing” into the mainstream.

The only other book of comparable influence is Twilight (2005) about the gay sparkling vampires:

But Twilight still falls short of end-of-period increase in word frequency and of course vampires were not exactly a novel concept in 2005 so I think Gidget wins.

Pax Americana hinges on good screenwriting

I think it’s really cool that some works of fiction were so successful! But most importantly my examples show that it is possible to influence the way people think by just exposing them to fictional ideas. Everybody knows about surfing even though few people do it and everybody has thought about alien invasion although we aren’t even sure aliens exist. Neither of these things were true in 1950. Microwaves, cell phones or the internet also become household items over this time, but these are tangible new products people have first-hand experience with. Surfing and alien invasion became known because works of fiction exposed people to them. In some ways it’s trivial that fiction can have this effect, but I think it’s not appreciated enough. My analyses also show that movies are an exceptional medium for practicing meme magic. I think people subconsciously have a problem telling movies apart from reality – I know The Sopranos are not real, but it certainly feels like its story happened to me.

The slightly schizo political takeaway from this is that the power of Hollywood as a medium of US soft power is hugely underappreciated. People across the world were drawn to the US sphere of influence in the 20th century to a great degree because they saw their awesome movies. Maybe you think it’s silly to think too much about the recent onslaught of terribly written, SJW-messaging Hollywood movies but I think that things like The Fembusters and Disney Star Wars break an important word magic spell over the world. Without stories to exercise soft power with, US foreign policy increasingly needs to resort to threats of economic and physical threats– including against my own country, ostensibly an ally – which will prove more costly and less effective.

Great post, East Hunter! Really like the investigation you've done here. The way ideas spread and the way they're accepted by the (retarded) public mind is an endlessly interesting phenomenon. From a non-fiction perspective I think you would likely appreciate this post: https://www.unz.com/isteve/who-drove-the-great-awokening-the-news-media-or-academia/