Reading fiction

Is there anything to novels after a decade of non-fiction?

I loved reading novels as a child and a teenager. But when I turned older, I discovered science and thought that it is pointless to read people’s opinions about psychology and other human matters when I can just read what the data says.

I didn’t read any fiction in well over a decade, but recently I decided to give it a try again. One reason is that although I don’t doubt the primacy of science I increasingly feel that there is a subjective element of the human condition which is not easily captured by scientific methods. I’m interested in everything about people, not just a specific discipline. The other reason is that I feel that human science has a creative crisis and it is in desperate need for new ideas. There used to be lots of ideas, models and theories in psychology, especially social psychology, but many turned out to be politically motivated garbage and either bled out in the replication crisis (like priming) or live on as zombie theories (like stereotype threat or recovered memories). Since the replication crisis the idea seems to go hypothesis-free, throw at lot of data at a learning algorithm and try to make sense of the (super-certainly replicable) model it creates. The best example for this approach is GWAS, a true 2010s phenomenon, which, as amazing as it is, didn’t tell us very much beyond things like that “genes are important for traits” and that “intelligence genes are expressed in the brain”. Another favorite example I have for impressive but ultimately futile data-churning is this study about geographical effects of personality which tells us – with 100% certainty, huge database, no p-hacking for sure – that there is a correlation of -0.01 between altitude and neuroticism. I understand the enthusiasm for these methods, they are better than p-hacking N=10 experiments like social psychologists or writing up your weird opinions as science like psychoanalysts, but something is amiss. It turns out that the causes of human behavior are complex and multivariate… which is exactly what a novelist or poet would have told you. After a decade of non-fiction, I wondered if they have any other interesting things to say.

Below is my impression of some fiction books I read over the summer, specifically with the eyes of a social scientist who normally works with quantitative data.

Oscar Wilde: The Picture of Dorian Gray

This was one of my favorite books as a teenager and a motivation for learning proper English. I expected the book to still be fun, which it was, but I was surprised to find that it is even more relevant for my newer interests in human diversity. In many ways, this is a story about how to deal with unpleasant truths about human nature.

Protagonist Lord Henry is a dispassionate observer of people who wants to get the truth instead of polite noble lies. If living today, would probably be writing a HBD blog:

“He had been always enthralled by the methods of science, but the ordinary subject-matter of science had seemed to him trivial and of no import. And so he had begun by vivisecting himself, as he had ended by vivisecting others. Human life – that appeared to him the one thing worth investigating.”

Lord Henry, like Arthur Jensen, is careful not to be bogged down by theory and instead go where the data takes him:

“But he never fell into the error of arresting his intellectual development by any formal acceptance of creed or system, or of mistaking, for a house in which to live, an inn that is but suitable for the sojourn of a night, or for a few hours of a night in which there are no stars and the moon is in travail.”

He does go to places following his data. Lord Henry knows about hedonic adaptation (happiness coming not from having things, but successfully passing challenges):

“sick with that ennui, that taedium vitae, that comes on those to whom life denies nothing”

as well as alpha widows:

“Do you think this girl will ever be really contented now with any other of her own rank? I suppose she will be married some day to a rough carter or a grinning ploughman. Well having met you [handsome, high class Dorian Gray], and loved you, will teach her to despise her husband, and she will be wretched.”

Lord Henry wants the truth about how people are, not white lies. Today, he would probably find it interesting that despite polite opinion to the contrary finding your mate is ultimately a market transaction, that society is largely a genetic meritocracy, or that the great causes of the modern West like anti-racism, climate change, COVID, feminism or support for Ukraine are some combination of scam, mass hysteria, and self-destructive religious frenzy. But he wouldn’t do anything drastic, beyond making sure he is not personally affected: he knows how people are, and he knows that they are not changing any time soon.

“To become the spectator of one’s own life […] is to escape the suffering of life”.

Dorian Gray, on the other hand, is like the guy who reads about “the Jews” on 4chan and goes on to shoot up a synagogue. When he hears Lord Henry talk about how love is fleeting and superficial, he leaves the actress he just proposed to, breaking her heart and driving her to kill herself. His cruel and self-destructive lifestyle is what causes his portrait (but not his real face) to turn ugly, the main theme of the novel. This is the polar opposite of the chill, cynical stoicism of Lord Henry, and should remind everyone of taking red pills too seriously.

A minor thing I only now noticed about this book is just how gay it is. Nominally, Lord Henry is married and Dorian Gray dates only women but the story is full of descriptions of male beauty and one can’t help feeling like some of the characters are more than friends. Of course, Oscar Wilde was not just homosexual, but a pederast and even went to prison for it.

Elizabeth Marshall Thomas: Reindeer Moon

Thomas is an anthropologist who lived with African hunter-gatherers for years in her 20s. She is, however, also a 20th century American woman, and both of these things are apparent in her book about Pleistocene hunter-gatherers in Siberia.

The story itself is silly. A caveman girl becomes a strong independent womyn after her parents die on a journey and she has to spend a winter in the woods with her sister. She then becomes the town (cave?) bicycle, has sex with every caveman she meets, breaks up her engagement and her sister’s because of her feelings, and everybody else is at fault for this. Fortunately, between a bear hunt and babies starving to death in the winter the cavemen are dedicated feminists, beating your wife is scandalous and women are free to divorce and even leave the tribe, so they put up with her behavior.

The world-building in Reindeer Moon is, however, seriously good. Thomas is great at describing how it is to live in a world where humans are wildlife, there is absolutely no civilization and life is largely about getting the minimum amount of calories not to starve. Fortunately, this takes up much more space than the drama. I read a lot of non-fiction about hunter-gatherers but never fully realized how it is to live like this (which is the majority of human history and likely the source of many of our behavioral adaptations).

One reason fiction is important is because it simulates immersion in personal experiences we can otherwise not have. Personal experience is not the same as scientific knowledge but it can give motivation or perspective for it. For example, I became interested in hereditarianism because when I lived in a bad area of Budapest, I noticed that the underclass people on public transport didn’t just lack money, they were different in other ways. They were often short and fragile and almost always ugly. They were restless like children, they fidgeted, vocalized and moved about while waiting for the tram, often chewing something or smoking. They were almost always sad and angry, every interaction even between friends and family members sounded like a fight. They were often injured, wearing bandages and casts or having scars. Coming from an upper middle class bubble you can believe that poverty is the consequence of generational trauma or capitalist exploitation, but with this experience I wasn’t surprised to learn that intelligence, health and wealth are genetically correlated and rare genetic variants (mutations) have a large effect on all. Some people get a bad draw of the genetic lottery so they end up sick, mentally ill, ugly and poor. A fiction author with a good eye for people can simulate such an experience like mine – or Thomas’s – for you in a novel [i].

Lev Tolstoy: War and Peace

In Hungary, you have to read these classic novels in high school and there are tests about book content and the author’s biography. Back in the day I read many long books other kids found boring but I found Tolstoy insufferable, so I did like everyone else and bought the abbreviated version (“Kötelezők Röviden”). After so many years I decided to give War and Peace a try as an adult.

Tolstoy is a very modern artist: his book is torture but you’re supposed to fawn over it. I really wanted to read this book but couldn’t. War and Peace is in desperate need for an editor, the text is overwritten, rambling, never getting anywhere. About 100 pages in, I gave up when a letter written by some countess to another was reproduced verbatim, multiple pages of meaningless teenage girl rambling including pointing out when she reached the end of a page writing. I wanted to read this book so bad that even then I skipped about 50 pages to where the Napoleonic war was already raging, but gave up again after a few dozen more because despite some good battle scenes and discussions of war strategy the text was just not going anywhere.

Not all books are good just because they are classics.

George R. Stewart: Earth Abides

This is easily the best novel I read now and one of the best in my entire life. Stewart was an English professor writing this in his 50s (published in 1949) so despite being sci-fi it is a serious, realistic, drama-free story written in crisp, precise English.

Isherwood Williams (Ish) is a PhD student in post-WW2 California when a virus wipes out ~99.9999% of humanity. This number is important: he is not left completely alone, but only a few dozen people survive even in a place like the San Francisco Bay Area. The survivors are too few for any of society to remain: there is no government, but there are also no bandit gangs, mutants, zombies or any other post-apocalyptic tropes. The story is about Ish’s life until his death as an old man. The survivors live a pretty comfortable life (by post-apocalyptic standards), mostly scavenging the remains of the old world. The power stays on for months and the water runs for decades. They keep cars serviceable for 20-30 years, and the roads and bridges largely last until the end of Ish’s life. They eat canned goods from grocery stores and hunt with rifles and ammo they loot from department stores. They have many children who mostly survive – there is no medical care beyond looting pharmacies but also not much infectious disease as all human carriers died.

There are many great themes in the book which are too realistic and un-dramatic to be greenlit for a modern Hollywood show (there is a 2024 adaptation but I haven’t seen it):

- Malthusianism. When the novel was written, virtually all countries on Earth were growing and it was common to worry that this will end civilization. (Ehrlich’s The Population Bomb was published 20 years later but the less-known Road to Survival by Vogt came out one year before.) Stewart hints that the disaster in the book is the natural consequence of having so many people on Earth, and population explosions and collapses happen to many wild animals after competition from humans disappears.

- Smart fractions and network theory. The 10 or so survivors are all urban people and (except for Ish, an academic) not very bright. They happen to have a carpenter who can maintain houses, but they have no farmer, no mechanic, nobody who can fix power plants or aquifers. Knowledge in a complex society is specialized, if you lose the few dozen people capable of maintaining a system, you lose that system. Learning these skills from books is not easy and may not even be feasible (see the next point). Intellectual activity requires a network of specialists. Ish is the only survivor interested in books or abstract knowledge, except for one son. When he dies young, science practically dies with him.

- People only make as much effort as they have to. This is probably the most surprising idea Stewart has which sounds right. Life is comfortable after the apocalypse, there are cars, free products from stores, for a while even power. Ish tries to convince his fellow survivors to learn to set up a gas-powered freezer, grow plants, prepare to fix failing infrastructure, build a government, maintain the city library, but they see no immediate need so they don’t do it. Civilization fails one small step at a time and neither is a wake-up call. When there is no more water, they dig wells and latrines. The next generation has never seen a modern city, only ruins, so they are happy to live as scavengers. The next one after this are hunter-gatherers as canned foods and ammunition perish. Ish’s greatest civilizational contribution is teaching kids how to make bows and arrows: this is technology they can use and improve. This sounds like third world behavior but remember: we have less than a dozen people who saw civilization, none of them are experts at building it, and there is no government organizing projects. Without a sufficiently large network of organized experts, civilization dies.

- Pro-natalism and eugenics. The one kind of rebuilding everybody is interested in is repopulation. Without much planning, everybody takes one of the surviving women as a wife (one man has two) and they have a baby each year. However, nobody is allowed to touch one intellectually deficient girl as they fear her condition is hereditary. (When a stranger tries this, they kill him.) Ish worries a lot that because only average or below-average people survived, there will be biological limits to rebuilding civilization.

- Workable Rousseauism. Violence is almost completely absent from Stewart’s post-apocalyptic world. This is because there is not much to fight about: goods are free and abundant, and access to women is tightly regulated: everybody gets a wife and that’s it. Plus, at least the original survivors happen to be reasonably nice people and not very young, and there is not much contact with outsiders. All of this is probably needed to eliminate violence at least for a generation.

Overall a very thoughtful and enjoyable book.

Cormac McCarthy: Blood Meridian

I always wanted to read this book because of its reputation as one of the great American novels. It’s a very gritty Western. I wasn’t very impressed by it, it feels long and repetitive. It circles through the following elements:

- Descriptions of desert scenes and astronomical/weather phenomena (these are great)

- Pointless, cartoonish violence

- Some semblance of a not very interesting story about a military expedition to Mexico.

McCarthy apparently researched the story well, so he uses vocabulary and includes details which are genuine for the mid-19th century American West. This is fun but not easy to read. He makes an effort to make the story as hard to follow as possible, key events are only hinted at or hidden between descriptions and violence which makes the novel dreamlike. The novel is best known for its violence which McCarthy describes in a distant, dispassionate way. It stops being shocking very fast and becomes ridiculous. Any time something weak or innocent appears in the story you can bet it will be gruesomely slaughtered in just a few pages. I chuckled at the end where they shot a dancing bear to death for fun because as soon as there was an animal on scene not actively killing people I knew what was going to happen.

The most interesting thing about this book is its depiction of the American culture of violence. Many of the characters (based on real people) are cold-blooded killers but otherwise very smart and calculating, even intelligent and well-mannered. This is strange for me as a European reader, violence here is strictly the domain of brutes and governments and there is no pop culture glorifying it (other than the one we import from the US). The takeaway is not that the US is a barbarous violent country, it’s that it’s so great that even some its psychos are gentlemen.

Frigyes Karinthy: A Journey Round My Skull (Utazás a Koponyám Körül)

Frigyes Karinthy is my favorite Hungarian author, a real Budapestian working mostly during the interwar period. You may know his idea of six degrees of separation, the realization that all people on Earth are connected through just a few others. For example, I’m connected to Stalin through just two handshakes (through my grandmother who once shook the hand of Communist dictator Rákosi in the 1950s) and to Muammar Gaddafi through just one (through an old uncle who worked as a contractor in Libya in the 1980s). My other favorite work by him is The Thermometer (page 65), a great illustration of measurement invariance – you can cheat the indicator, but not the construct, by breathing on the thermometer in the cold.

Karinthy had a very interesting inner world. In this book, detailing his 1930s brain surgery in Sweden due to a benign tumor he writes (about a long distance call from Hungary):

“The telephone wire runs, and within the wires the words, to and fro, within a fraction of the second, but what does the wire care about human voice? The poles don’t care either, they are made of wood, mutilated, cut-down invalids of the global society of trees. They only care about other trees, maimed and moaning as they are; if they ask anything, it’s if the telephone wire has a message for them. Are you coming from far away, Brother Wire? – the Stockholm telephone pole asks. What’s up in the South? Is it true that the cherries are already blossoming, even though the trees here only will next month, and me, never?” (Translation mine.)

Treating inanimate objects as having thoughts and feelings like this is called animism and it is common in kindergarten-age children. One of the reasons I like Karinthy is because I also have these animistic daydreams when my mind is wondering. Sometimes I catch myself thinking how buses feel about having to carry that many people or if small buildings envy big ones. Are some adults more prone to this childlike thinking than others? Is this related to intelligence, creativity or humor? This is what I mean when I say that fiction can be hypothesis-generating.

Jorge Luis Borges: The Aleph and Other Stories

I always wanted to like Borges more than I eventually could. I was especially impressed by his 1940 Tlön, Uqbar, Orbis Tertius (not in this collection) a story ahead of its time about some people tracking down facts about the mysterious, hidden lands of Tlön and Uqbar only available in a certain edition of a certain encyclopedia. It reads like an SCP Wiki story. It must have been very cool to live in a time when you could discover serious new knowledge in a library of rare books instead of immediately getting all the knowledge about everything via Wikipedia and ChatGPT [i].

That said, most of Borges’ stories circle this style and content but never really get there. You will recognize early versions of lots of well-known sci-fi and horror tropes though. Sometimes in fiction it takes generations of authors to really nail down some idea and while the latest are the best, you must give credit to the original inventor of the idea, which Borges often is. I always felt this way about Shakespeare too, he is not that great before you realize how many people he inspired and that his ideas are getting copied and reshuffled by Hollywood to this day.

Overall impression

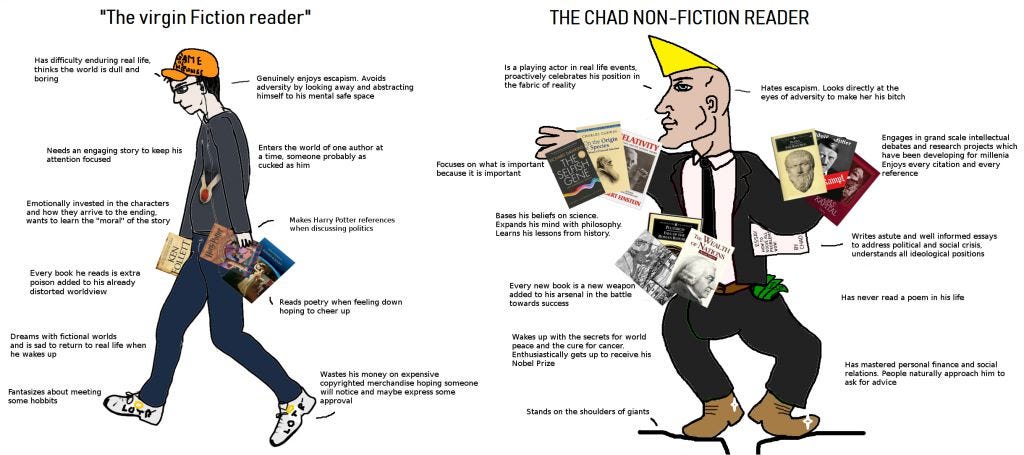

Reading fiction is great and you should try it again if you ever stopped. It’s not an alternative to science, it’s entertainment, not work or learning, but it beats movies and games (not to mention short-form brainrot which should be treated like a drug). There is something psychologically right about imagining a story you read with your mind’s eye, the immersion in fiction creates perspective and there are lots of ideas in the works of good authors that are either valid on their own or even inform scientific work.

Many modern social scientists get all their ideas about people from R-based analyses of huge datasets and online conversations with like-minded people. Many also live in not just first-world, but upper-middle-class first-world bubbles and have little personal contact with raw data or the experiences of people unlike them. This carries the risk of becoming what we call a “barbarian professional” (szakbarbár): a person highly skilled in a narrow discipline but missing perspective, somebody with a good hammer who sees every problem as a nail. I understand the benefits of quantitative, data-driven science and I’d pick that one too if I had only one way to learn about humans. But being good at statistical genetics or psychometrics or anything else doesn’t let you know everything about the human condition because all these disciplines have limitations, and reading fiction is one way to fill in some of the gaps.

[i] Of course, fiction can create a false narrative too, like the anti-psychiatry literature which made people lobby for the closure of asylums and landed thousands of deeply ill people unfit for society on the streets, or Hollywood fantasies about ass-kicking tough women and dindu nuffin gentle giants.

[i] Sometimes this still happens though: a few years ago a mention of Markland, the Viking name given to Labrador, was discovered in a 14th century Genoese codex. This shows that knowledge of the Vikings’ discovery of America survived almost to the time of Colombus. Incidentally, Borges also wrote about how the Scandinavians invented much of the modern world, including discovering America, before everybody else.

For Blood Meridian I recommend reading some more background on the Glanton Gang (which makes the violence seem less cartoonish and more realistic) and also "Gravers False and True: Blood Meridian as Gnostic Tragedy", a theme that pervades Mccarthy's works.

"Without a sufficiently large network of organized experts, civilization dies." boy, I have an author for you: prof. Lucio Russo.