Everybody wants to be happy, but we don’t really know how to do that. A large proportion of individual differences in life satisfaction – measured by self-reports, as we don’t really have any other tool than can measure this - can be explained by genetic factors. As a matter of fact, life satisfaction is strongly correlated with things like depression and neuroticism, meaning that on the genetic level these traits are very similar. (Or much rather that people can’t tell if they are unsatisfied, depressed or neurotic on the questionnaires the geneticists give them – could you? – a phenomenon known as spurious pleiotropy).

If you studied any psychology in college or even in high school, you probably heard about set point theory – everybody basically has a biologically determined level of happiness which is hard to change, and both amputees and lottery winners return to their baseline level of happiness shortly after their (mis)fortune. This seems to be the same thing as high heritability, but heritability actually is very far from 100%, and people do experience big shifts in life satisfaction both in the short and the long term, especially after critical life events. There is no set point, I guess you could argue there is an attractor though.

So, what makes people happy? An infinite number of things, probably, however, I was inspired to write about happiness by a few studies which look at concrete predictors of happiness with very convincing designs and find very surprising things. The first of this series is about the number of hours spent in work. Are people happy when they work more? And is this different in men and women? This question is also a major test of feminist ideas about how equal representation of the sexes in the workplace is great for women. You were obviously attracted by my clickbait subtitle so I’m not keeping you waiting any longer.

The study for today is:

Abstract (emphasis mine):

“This article uses random and fixed effects regressions with 743,788 observations from panels of East and West Germany, the UK, Australia, South Korea, Russia, Switzerland and the United States. It shows how the life satisfaction of men and especially fathers in these countries increases steeply with paid working hours. In contrast, the life satisfaction of childless women is less related to long working hours, while the life satisfaction of mothers hardly depends on working hours at all. In addition, women and especially mothers are more satisfied with life when their male partners work longer, while the life satisfaction of men hardly depend on their female partners’ work hours. These differences between men and women are starker where gender attitudes are more traditional. They cannot be explained through differences in income, occupations, partner characteristics, period or cohort effects. These results contradict role expansionist theory, which suggests that men and women profit similarly from moderate work hours; they support role conflict theory, which claims that men are most satisfied with longer and women with shorter work hours.”

I don’t like copying abstracts but this one does a better summary than I can probably come up with. Still, let’s give it a shot. The biggest deal about this study is that the data used in it even exists and available for research. It merges data from multiple longitudinal panels: huge, often nationally representative studies where people were interviewed multiple times over their life about – among other things – how many hours they were currently working and how satisfied with their life they were (of course, this was based on a subjective self-report rating). There were many similar studies before, but they fell short due to one or several of the following things: 1) they did not sample the same people multiple times, 2) they did at categorical divisions of work time like “full time” and “part time” instead of actually looking at the number of hours worked which can reveal a nonlinear pattern, 3) they did not look at sex differences.

One thing we can do is to look at the relationship between hours worked and self-reported life satisfaction, called a random effects model. These relationships look like this:

As you can see, the trend is that in most countries the satisfaction of men increases with hours worked. Women’s satisfaction either doesn’t depend much on hours worked (and it is on average higher), or shows a small increase (US, East Germany), but more typically a small decrease. This doesn’t depend much on whether they have children: the blue and purple and the green and blue lines go together. Despite stereotypes, Koreans seem to have the most normal attitude to work in that they don’t report maximum enjoyment at maximum hours worked.

Of course, this model (being a random effects model using partial pooling) conflates within-individual and between-individual effects somewhat. The relationship between hours worked and satisfaction can be heavily confounded. Maybe the people who work only a few hours tend to be systematically different than those who work more, possible in ways that affect their life satisfaction: for example, they might be sick, less educated or poor. The right way to do this analysis is to run a so-called fixed-effects model: a model which only estimates within-individual effects: how does life satisfaction change within the same person as a function his/her own number of hours worked?

There is a lot to unpack here, so let me just borrow the author’s words again:

“in every single country, a statistically typical father gains life satisfaction when increasing his working hours. A typical childless man also does, but often a bit less than a father, while a typical childless woman tends to profit less from longer working hours and a typical mother less yet. Contrary to all other groups, a typical mother is not more satisfied when working longer hours, except possibly in East Germany, Russia and Korea, but the large confidence intervals do not allow any clear inferences.”

You can see this for yourself. Almost all lines slope up to the right, but the blue and green ones (men) tend to be steeper than the red and purple ones (women). Blue lines (fathers) tend to rise especially fast, while red ones (mothers) tend to be especially flat – simply put, working more if you have a kid may be a good idea to increase your life satisfaction if you are a man but not if you are a woman. East Germany is a big exception though!

But so far it seems that the feminists were right: while the returns on more hours worked are lower for women, they are there, and one of the reasons they are lower is because women in most countries tend to just be more satisfied than men, so they have less to gain!

We need to consider though that there are lots of things than can change over the course of the same person’s life that can correlate with both hours worked and life satisfaction. The most obvious is income. Maybe if you are a woman – possibly even a mother – you don’t especially like working more but you like that it brings more to the table, so the outcome is a net positive. Maybe it’s not the increase in your pay that matters, it’s that you like being promoted to a better job, even if it entails working longer hours.

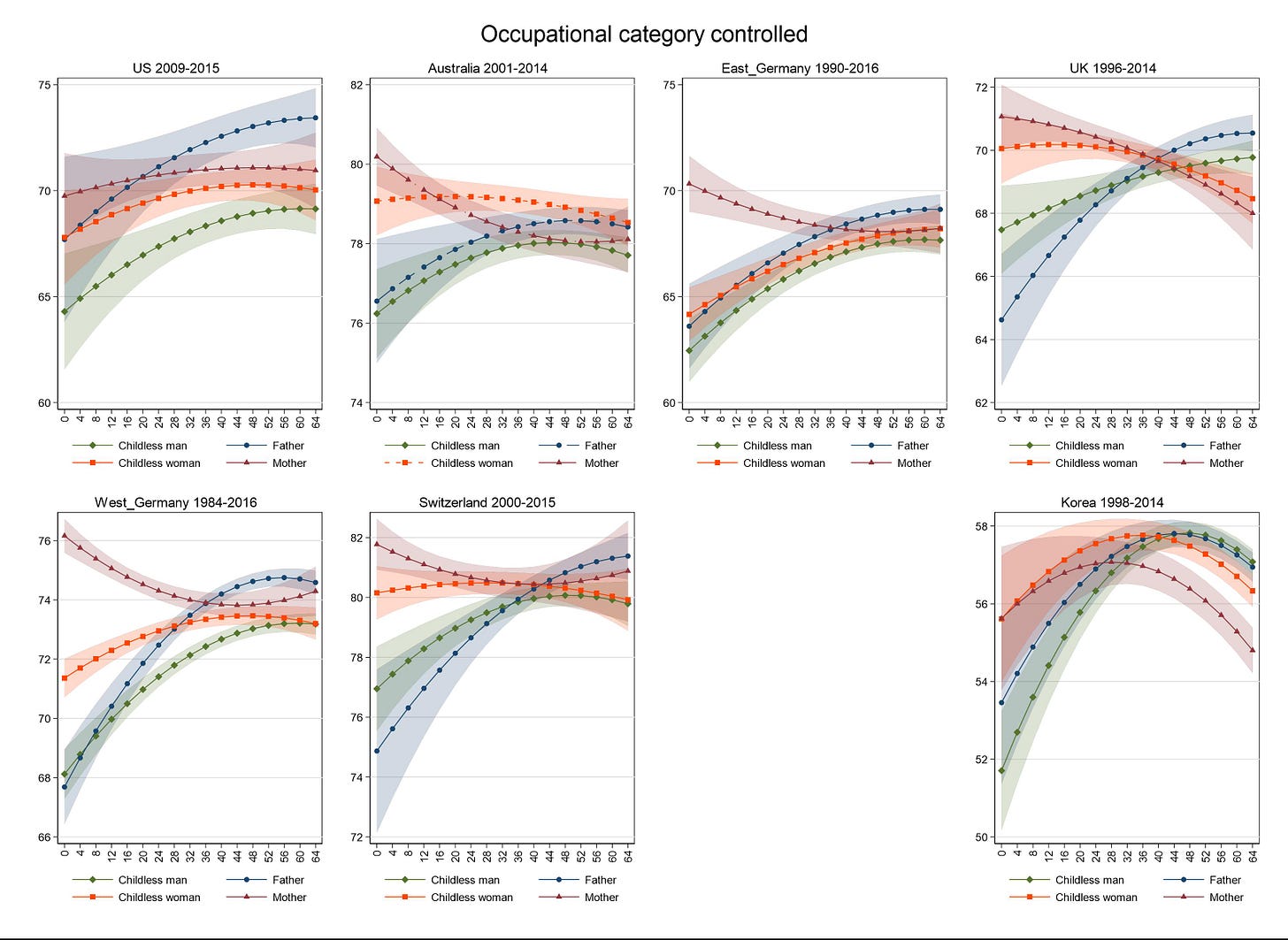

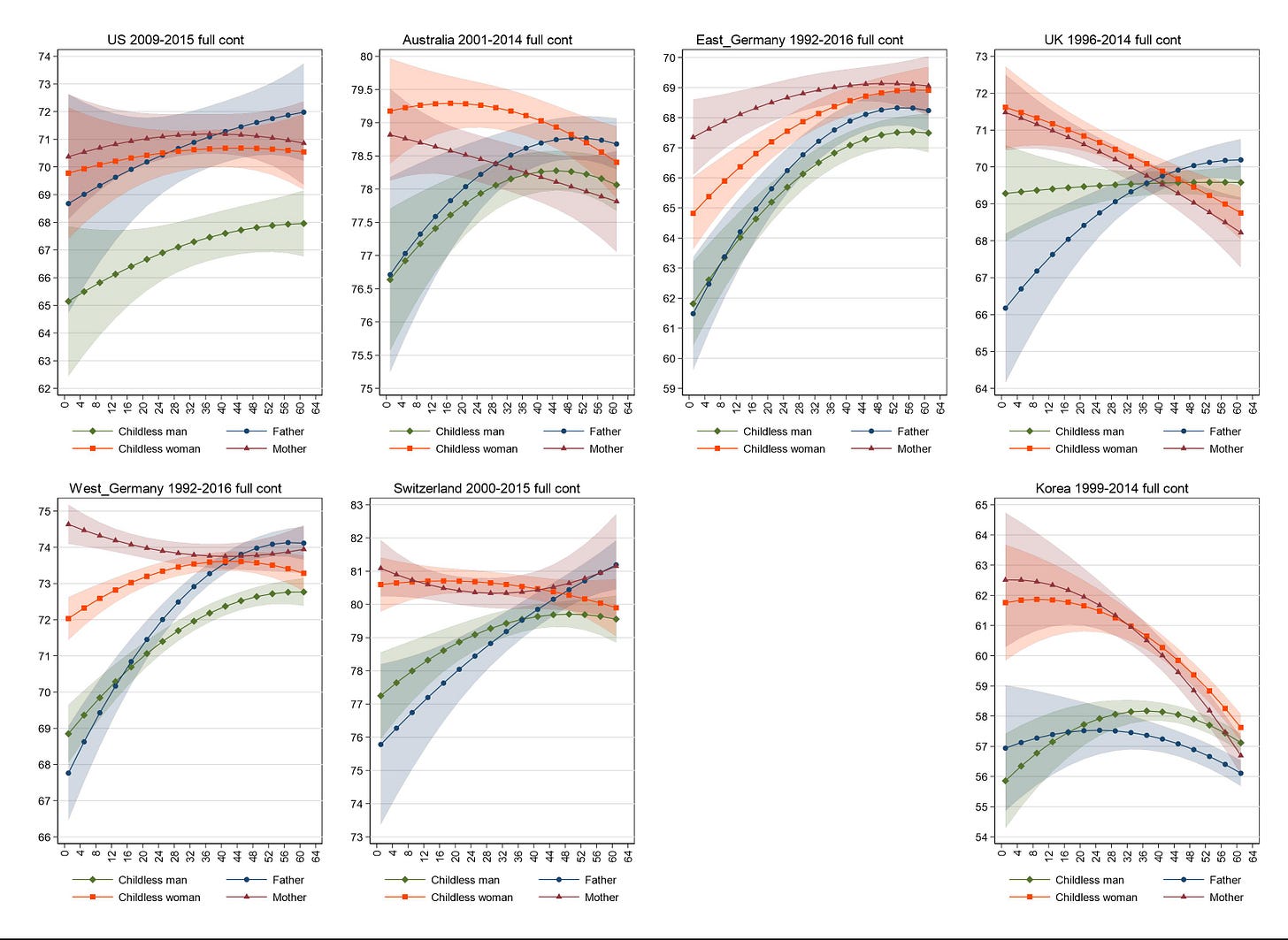

I think this is exactly what’s going on and so does Schröder once we dig into his supplementary material. Controlling for occupational category does this to the curves (not all countries provide data that allows these analyses, hence the missing panels):

and controlling for income does this:

You can see that (except for those weird East Germans!) now the red and purple lines stay flat or decline to the right, while the blue and green ones keep trending up. What this means is that for women, more work is indeed only better for life satisfaction to the extent it is associated with a better or at least better paid job. Once you control for these, they don’t like working more at all. Men, however, and especially fathers, appear to just like working more for work’s sake!

And they share this opinion with their wives.

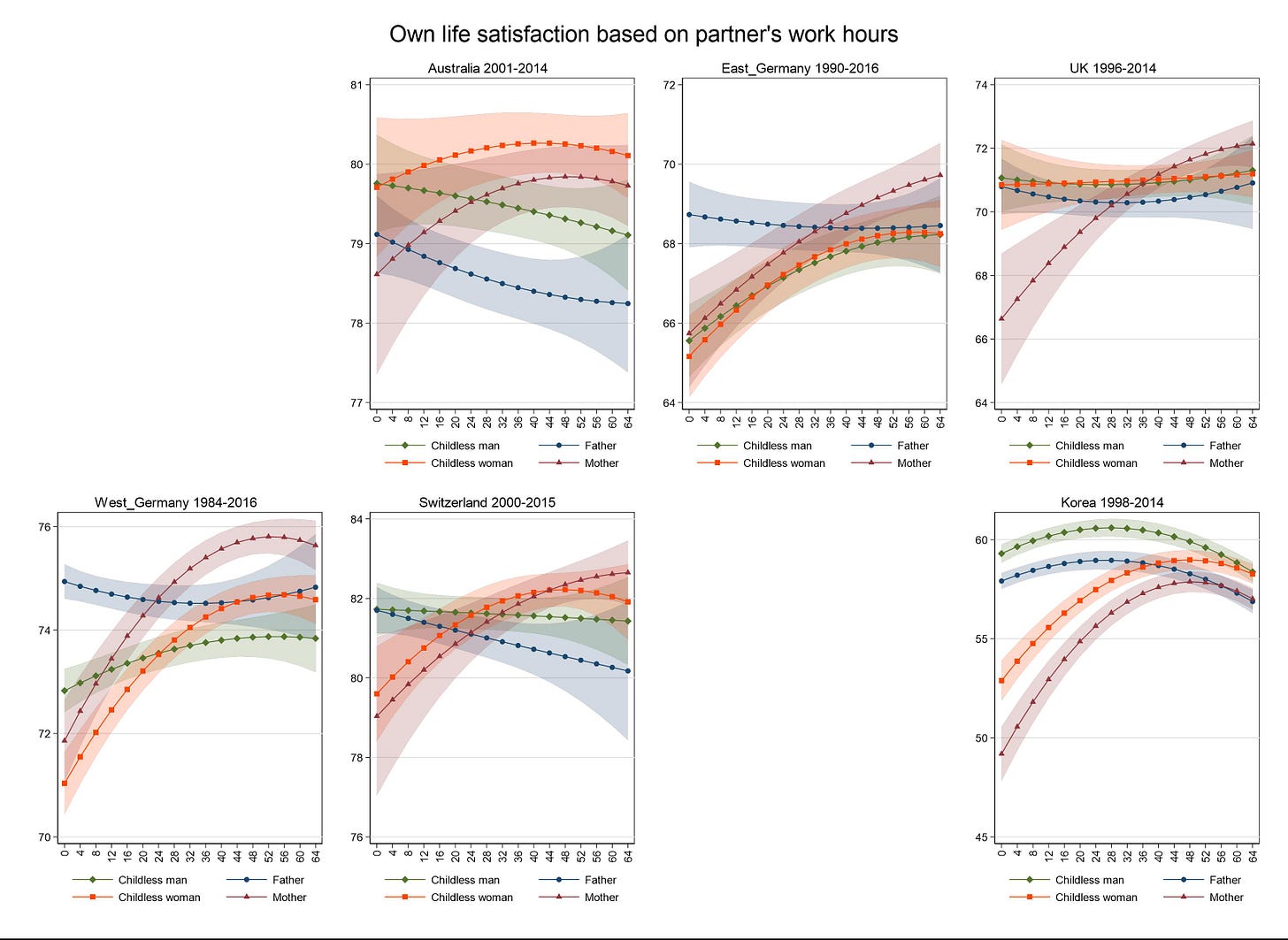

One of the most subversive plots in this paper is this one, which shows life satisfaction as a function of the hours the respondent’s partner works:

Women like it if their partners work longer, while men don’t, a finding that replicates across all countries. Of course, there is no control for job characteristics here, so maybe it’s just that women like the extra money the husband brings home, but still, both sexes seem to be quite happy with the arrangement where it is the man who does most of the out-of-home work providing for the family.

For a final analysis, the author considers between-country differences – could these nefarious patterns go away after we have done even more feminism and made the sexes completely equal in a hypothetical utopian country? They draw data from the World Values Survey to rate countries on gender equality and estimate how the results would look in a perfectly gender-equal and a perfectly gender-unequal country. (This sounds esoteric but if you know statistics you know it’s just a matter of lengthening regression lines until some value – basically like forecasting the weather, with similar reservations about accuracy.)

Unlike many others, this is one of those sex differences that seem to diminish somewhat in more gender-equal countries, but not enough to be eliminated. Based on the available data, we would still comfortably expect women to gain less in happiness from working more in a perfectly gender-equal country. The biggest difference seems to be the diminishing returns on extra working hours over the normal weekly limit – I think this is driven by Korea which shows these patterns in univariate analyses, and which has relatively low scores on this gender equality measure. Maybe in this country, working very much is necessity rather than a choice to make more money.

In a way, this study is about progressive thought in general

It’s very rare for a scientific paper to be this good, this consequential and ignored so much. Schröder’s work was only cited 15 times in the 3 years since it was published (at the time of writing) and only one challenged its findings – not really in anything substantial. This is even though this paper is a frontal attack on an early feminist idea, namely that women’s participation in the labor market must match men’s, both in quantity and in quality. Schröder uses an incredible dataset to test this idea and finds it lacking: men actually like working more, even if it brings them no material benefit, while women are mostly in it for the money, and even that makes them less happy than it does men. Both men and women prefer the arrangement where the man works more outside the household and women less.

Of course, we have known this for a long time. It is well-known that men and women have very different preferences in both their personal and professional lives, that these differences almost never diminish and in fact usually get bigger in more gender-equal countries, suggesting that they are not caused by a lack of feminism. For example, surveys of highly intelligent, highly educated and overall highly successful women (in this case, the Study of Mathematically Precocious Youth, a longitudinal study of people who did a top 1% math SAT at age 13) report job preferences like this:

When you want to fill your company board or your parliament with 50% women as some countries now want to enforce by law, you have to keep in mind that not only do you have to choose from a much smaller pool at this IQ level due to sex differences in the distribution of intelligence, you also have to face the fact that many of the women who are definitely 100% up to the task intellectually just won’t be interested to take it. They have different interests in life than shouting at people in a company meeting or doing quarterly reports for a gigantic soulless company. It is no wonder that despite all the gains of the feminist movement in the US in the past half a century, women did not become happier.

This of course fits into a larger pattern of progressive social movements. Progressives seem to like people in theory, while conservatives tend to like them in practice. Progressive movements are often about some lofty goal that looks good on paper, but little thought is given to drawbacks, externalities and tradeoffs, because they are not actually about helping the target group, but about the activists’ narcissistic fantasies or bad conscience. Members of progressive movements are often either not members of the group the movement seeks to liberate or highly atypical members. It is not particularly surprising that progressive movements have a tendency of backfiring and hurting the group they were supposedly liberate the most. For example, Communism was not only dysfunctional, but it seriously hurt the working class it was supposed to elevate the most. Look at Hungarian GDP and life expectancy data before and after Communist rule, compared to a neighbor:

While Austria has always been the more developed country – the low numbers on the GDP chart make this difference smaller than it was in early years – its development truly diverged from Hungary once it became part of the Capitalist block and Hungary the Communist block after World War 2. In the system nominally designed to uplift the working classes, economic growth was sluggish while life expectancy stagnated, and both only started catching up once the Hungarian economy was restored to the realities of the free market. Despite explicitly being aimed to raise up the working class, Communism failed at it terribly. Communist ideology was of course also a verbal ploy to rationalize Soviet presence in whatever the Red Army managed to conquer in World War 2, but nothing prevented it from doing what it preached, at least after Soviet rule was solidified. It didn’t do it, because it was not actually about working-class prosperity: it was about the imperial aspirations and personal narcissistic fantasies of activists, and later, of Soviet leaders. The words were about the working class, because you normally don’t just say “I will occupy your country and run it into the ground because I’m a psycho”, even if you are Stalin.

An even better example is Black Lives Matter. This progressive movement, nominally launched to save the lives of American Blacks, arguably killed more Black people than any other social movement in American history, absolutely including those with explicit anti-Black racist motives. This movement successfully demanded the de-policing of American cities, which caused an explosion of both homicide and traffic fatalities, both mainly claiming Black victims.

(Charts and much commentary by Steve Sailer).

Women and minorities, beware of progressives! They are very interested in your welfare – don’t let them take it from you!