Let’s ask an important question today: does sexual intercourse improve sleep?

I like to think about what things people take for granted may actually be wrong. However, I never thought too much about this „sleep after sex” thing, I think because I took it for granted myself. People believe that sex improves sleep, especially for men. We are all familiar with the movie stereotype of the man saying something like „Goodnight honey” and going to sleep right after sex leaving a frowning woman hanging. (There are two TVTropes pages sort of about this, although not as directly as I thought when I looked them up.)

TVTropes aside, I’m not making this up to do audience capture: there really is research about these beliefs, ironically much more than about the phenomenon itself. Let’s look at some papers.

This is an online survey of just over 1000 people who were asked if different types of sexual activity – any sex with a partner, sex to orgasm with a partner, any masturbation or masturbation to orgasm improves 1) sleep quality or 2) sleep onset (how fast you can fall asleep) This is basically somewhere between an opinion survey and an observational study: people weren’t exactly studied here in the strict sense (that would involve something like interviewing them about sleep quality after sex happened), but you can argue that their opinion on this matter comes from personal experience so it’s not like a political opinion survey when you give you opinion about things you don’t necessarily experience yourself, like abortion or taxing the rich.

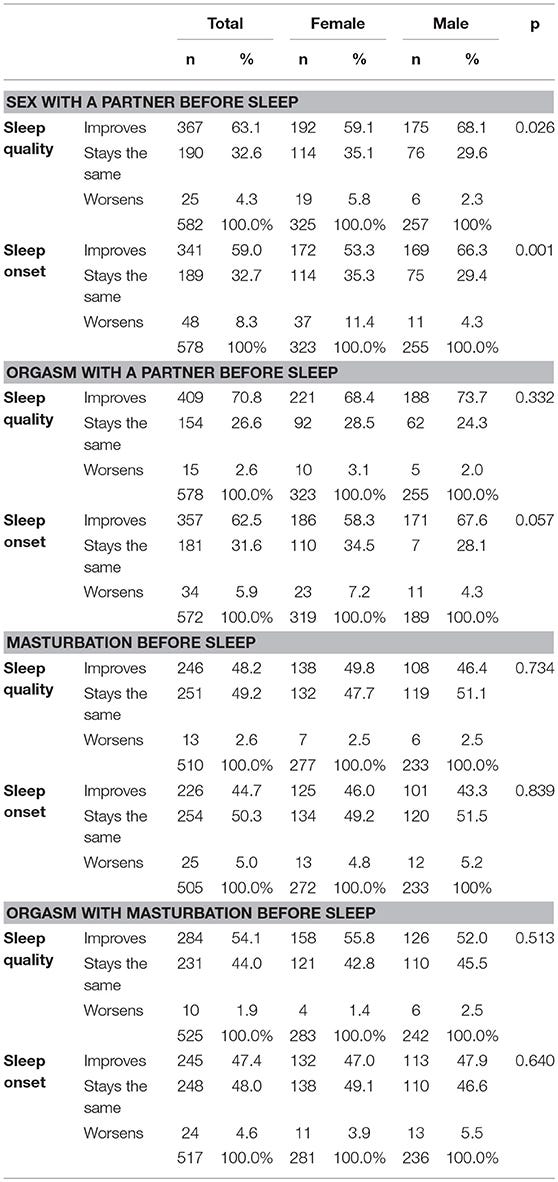

The main results are in this table:

As you can see, a solid majority, both men and women, said that all forms of sex (except masturbation without orgasm – why would you do something like that?) improves sleep. This trend is probably statistically significant across the board – the p-values are for the sex interaction. Men are more likely to women to attribute a sleep-improving quality to sex with a partner in general, but when we specify that an orgasm was reached, there is only a borderline trend for a sex difference in sleep onset. People really seem to believe that 1) sex improves sleep but 2) for women this only really works equally well if they also achieve an orgasm which as we know they don’t always do.

And this study has been replicated!

From the abstract:

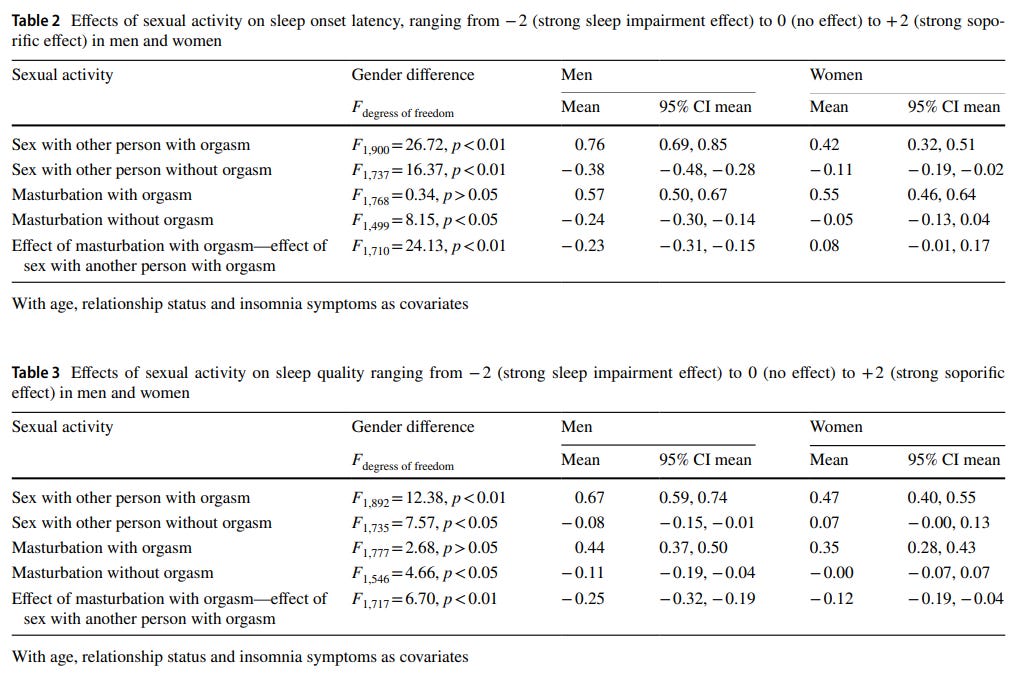

„In all, 4000 persons, aged between 18 and 55 years, were randomly drawn from the Norwegian Population Registry and invited to participate in a postal survey. The respondents were asked how sexual activity with another person, with or without orgasm, and how masturbation, with and without orgasm, influenced sleep latency and sleep quality. A total of 1080 persons participated (response rate 28.2%) of which 56.1% were women”. […] „Sexual activity with another person, with an orgasm, was perceived to have a relatively stronger effect on men compared to women in terms of sleep quality. Sexual activity without an orgasm was by men reported to have a sleep impairing effect, whereas the perceived effect reported by women was equivocal. Sexual activity with orgasms was perceived as having a soporific effect in both men and women.”

Here are the results if you want a level of detail just between the excerpt from the abstract and actually clicking that link to the paper:

There is a lot to unpack here and you can nitpick that some details from the previous study are different here, but the big picture still is that people believe that: 1) sex improves sleep 2) especially for men and 3) especially if an orgasm is reached, which I guess you may take for granted if you are a guy but not if you are a girl.

Also, I love that some people got money to send out invitations to some random Norwegians to basically give their opinion about TVTropes memes for 60 dollars, and actually wrote it up as a scientific paper. We need more of this energy in this world!

And guess what: although to this point (we are in 2020!) - aside from a small, but EEG-based study in the 1980s with negative results – there is no reference in any of these papers to any study that proves that this sleep-improving quality of sleep actually exists, the beliefs themselves were investigated a third time!

Gallup et al (2020): Sex Differences in the Sedative Properties of Heterosexual Intercourse

This is a much smaller sample – just over 200 people – but it contradicts the previous two! From the abstract:

„Postcopulatory somnolence was also enhanced by orgasm in both women and men. However, with or without orgasm, women were more likely than men to report falling asleep after sex. Consistent with the possibility that seminal fluid may contain sedative-like properties, women who were being inseminated were also more likely to fall asleep after sex.”

Participants here were more explicitly asked about their own sexual experiences, but they were still not studied in a laboratory or anything like that. This included lots of evo-psych focused questions about things like orgasm frequency – if you are interested, 17% of women and 2% of men reported never reaching an orgasm during intercourse. The respondents agreed that sex is sleep-enhancing, but here it was women who reported falling asleep more easily after sex!

What do we make of this? Well, let’s look at the fourth replication, which now includes real-life data to see if the stereotypes are true or not! I can now admit that reading this paper was my main motivation to write this post.

Oesterling et al 2023: The influence of sexual activity on sleep: A diary study

This is a really neat paper because it contains both an opinion survey – which the authors call a cross-sectional study – and, for the first time since that 80s paper, an actual empirical study. We need to get down to methodological details before we talk about that last part, so first let’s bite off something we can chew.

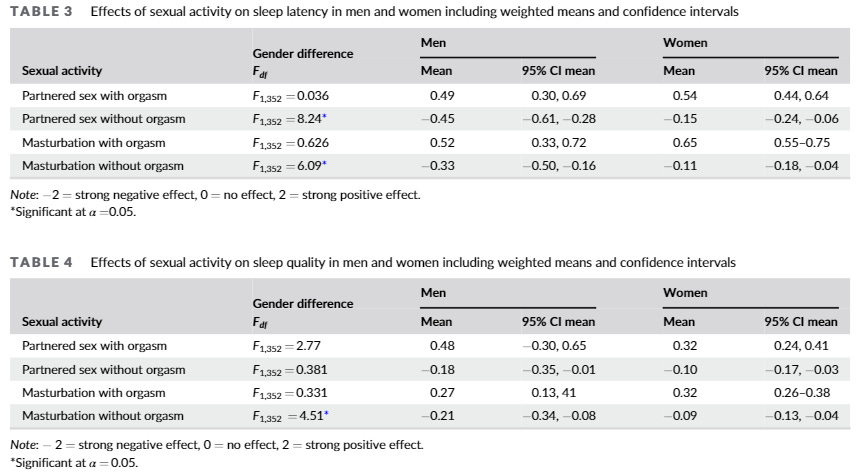

The main opinion survey results are these:

The study is designed to be a direct replication of the Pallesen paper, and the results really are similar. Both men and women believe that orgasms – whether they are reached by sex or by masturbation – improve both sleep quality and sleep latency. Interestingly, they don’t prefer sex to masturbation much! Also, there seems to a belief that if you start sexual activity but don’t have an orgasm, the effect is the opposite – it makes sleep worse. The only sex interactions were also in this domain: people believed that it is worse for men’s sleep to masturbate without reaching an orgasm, with semi-believable interaction p-values of p=0.01 and p=0.03.

But now comes the twist: these authors actually looked at real data to figure out if all of this is true! To accomplish this, they had 159 people fill out a diary each morning for two weeks about their sexual activity over the previous day and their sleep quality during the night. A bit more than 2000 diary entries were collected. There were just over 250 entries reporting some kind of sexual intercourse, about two-thirds – about a half in women, and about 90% in men – leading to orgasm. These numbers are about what I would guess in a mostly undergrad student sample.

Such data enables a longitudinal, within-subject analysis design, which is the best we have to investigate this question. Basically, we are using people as their own controls: we are looking at whether the same person systematically reported faster/better sleep after having sex, compared to his own level on days with no sex. (Of course, only people who had sex on some days but not others, and had meaningful variance in their sleep quality, are informative in this design.) This design is called mixed-effects modeling or multilevel modeling. They are used a lot in research that wants to determine what influences sleep (like this study here) or if sleep quality influences something we experience during the next day.

The problem is that most statistical procedures assume the independence of observations: there should be no relationship between data points beyond what is caused by the variables we study. By collecting over 2000 diaries from 159 people, we are violating this assumptions: each person provides up to 14 diaries, presumably with similar numbers, because there is a lot of within-individual similarity in just about anything – some people just always say they slept well. (In this study, the intraclass coefficient was 0.42 for sleep latency and 0.24 for sleep quality, meaning that this much of the variance in the 2000 observations is accounted for by who we ask, and the same person’s sleep latency is only 58% and his sleep quality is only 76% as variable as if we pool data from all kinds of people.)

This is a problem because we are seeing a much larger sample than what we actually have. Imagine a scenario where sex doesn’t improve sleep, but on average, people who have a lot of sex tend to report great sleep – they are just easy-going, extraverted people with a great life! If you would just naively calculate a sex-sleep correlation from these 2000 diaries, each participant would be represented by up to 14 highly similar data points, giving you a fake sample size 14 times as big as you really have and greatly inflating statistical power. (As an even more obvious example, you could just imagine establishing that women are taller than men, N=10000, by measuring a particularly tall woman and a short man 5000 times each.) Not a good idea. You could of course calculate an individual average of all observations, and work with just 159 means, but then you couldn’t compare people to themselves, and you would end up with much fewer observations that you have.

The solution to this problem is to include a mean for each person in the model called the random intercept. (Mixed effects model use a statistical trick called partial pooling to make this cost you only 1 degree of freedom.) What we are looking at now is deviations from the person’s own mean. Maybe some people almost always have sex and always sleep well – but is it true that when a person has sex, he sleeps better than he normally does? Neatly, we also can put the individual means we just threw out back in the model as a so-called Level 2 variable – something that only varies between people, not within people – to look at between-individual differences. When we do this, we can totally conclude things like „people who have more sex sleep better on average, but the same person doesn’t sleep better than his average after having sex” (the papers I linked are not about sex, but the logic is the same).

In this sex paper they only do the first part: they look at whether people slept better after sex than their normal level with no sex. Drum roll:

There really is – sort of – an effect! Masturbation didn’t change sleep quality or latency at all. It looks like people really fall asleep faster though if they have sex (with orgasm) with somebody! I normally don’t like models which look at this many things and find so few effects to look at, but p=0.002 in the expected direction is convincing. I’m on the fence what to think about the sleep quality effects: the effects are in the expected direction, but the significance level is p~0.05 which we are normally not very excited about. Also, it doesn’t seem to make a difference if you reach an orgasm, which seems hard to believe. In either case, there is no evidence for a sex interaction, so sex seems to – at the very least – make both men and women make fall asleep faster.

Stereotype accuracy vindicated?

As we know, most social psychology findings are p-hacked garbage, but stereotype accuracy is an exception. Fitting the traditions of the field, stereotype accuracy is barely taught at universities, hushed up in public discourse by experts, and stereotypes are usually decried as something horrible that only racist and sexist people have, even though they tend to be highly accurate. If people are so good at judging others, even in the face of so many incentives not to do it, how great must they be at observing something as obvious as whether they sleep better after having sex?

Well, I’m not that impressed overall. According to several large, well-replicated studies people think that sex improves sleep quality. This is not borne out by the data. This is 0/1. They believe the same about sleep latency – let’s say for the sake of the argument that this is vindicated by the data, but I’ll bicker about this some more. 1 out of 2. They also say these effects are stronger than men than in women (at least in 3 out of the 4 opinion surveys) – this is not supported by the data, in this or the opposite direction. 1 out of 3.

But what about the sleep latency finding? Well, this may just come from a design problem. See, what happened is that people were prompted in the morning to report previous day sexual activity and previous night sleep – a few days after they said in a survey that sex improves sleep! This invokes something called recall bias: you just said you had sex last night, you remember your opinion from a few days ago saying that sex makes people fall asleep faster, so even if you don’t realize it, you are pressured to say that you fell asleep faster than you actually did. A better way to do this would be to ask about sex before going to bed and about sleep in the morning – but even then we would have the problem that people are not great at self-reporting sleep latency (many such studies). Ideally, you would have people wear a mobile EEG device which objectively measures their sleep patterns. Until then, we can say that maybe sex makes you fall asleep faster, but it doesn’t make you sleep better.

Sleep quality and quantity after sex will be confounded by caffeine and alcohol consumption and potential later/earlier onset of sleep following evening sexual activity. Even a well designed study using measuring devices will have to account for more variables to examine any effect.

And yes, I slept very well last night.