There is widespread belief that people somehow learn to relate to others from their parents. So men have “mommy issues” when they simp for women, and BPD girls with terrible personalities “had a bad relationship with their fathers”. These observations might be correct, but our priors should firmly be against a causal interpretation. When parents with certain bad characteristics have children with other bad characteristics, more often than not this is due to genetics, not child rearing, also known as the first two laws of behavior genetics. Mothers who smoke during pregnancy have kids who do poorly in school and poor people commit crimes more often, but these are not causal effects – all of these problems mostly reflect low intelligence and impulsivity which are heritable characteristics.

Noticing the importance of genetics for social outcomes has been a rebellious, but increasingly mainstream position for many decades now, relatively safe for your career as long as you don’t apply this to race differences. But I think it’s harder for many people to also bite the bullet on relationship patterns, so today we will talk about how much early attachment matters and how much of it is learned or inherited.

A crash course on attachment theory

Traditionally – from the first time state-run hospitals and orphanages existed until pretty much the 1970s – small children were often separated from their parents when they needed extensive medical treatment. This was not great: children have a psychological need for an intimate connection with someone personal, so they developed serious mental problems if they were abandoned without their parents, even if they had other children and helpful personnel in the institution. The psychologist René Spitz described the resulting condition as “hospitalism” – depression, delayed development, communication problems, persistent if the child’s condition was not improved.

So far so good. It is reasonable to assume that seriously depriving small children from parental contact for weeks or months is damaging, maybe even long term. Even short term you wouldn’t want to scare or inconvenience them. However, classical attachment theory went one step further and assumed that even in children who have their parents nearby, the quality of their relationship is causal for a lot of things. Different parents respond to their children’s behavior in different ways, so children learn different patterns about how a relationship works, which they internalize and maintain for life. A securely attached child will play and explore when their parents are nearby, cry when they leave, but calm down when they come back. An insecurely attached child will either not care if their parents leave them – this is called “avoidant” attachment – or cry unconsolably even after they return, called “ambivalent”. The way to assess attachment in small children is to actually play out this situation where the parents leave the child alone and then return, a procedure called the Strange Situation. In adolescents and adults, attachment can be measured using questionnaires about their relationship to their parents, romantic partners and adults. The theory is that people who learned a secure attachment style from their parents as babies or toddlers will maintain this secure attachment into adulthood, and grow up to be adults with healthier relationships and a generally more successful life. This implies that parents have a huge responsibility in shaping the life of their children. If you take a standard psychology intro course, this is pretty much what you will learn.

Let’s look at claims of attachment theory in detail, specifically that:

1) attachment style is a long-enduring pattern, with the same person having very similar attachment as a toddler and as an adolescent or adult;

2) attachment style is related to good life outcomes;

3) and attachment is shaped by parental interactions in babies and toddlers and remains stable from there.

The stability of attachment

People doing research on attachment realized that they need long-term longitudinal data so they designed studies where they studied babies and followed them up until they were adolescents or adults. At first glance, the correlation between attachment in small children and adolescents is not that great. The 2002 meta-analysis by Fraley (with some interesting discussions of temporal modeling) found a correlation of r=0.27 value between age 1 and age 19 (N=218). A big study of several hundred people also found all sorts of significant correlations between measures of attachment in toddlers and young adults, none of them strong however.

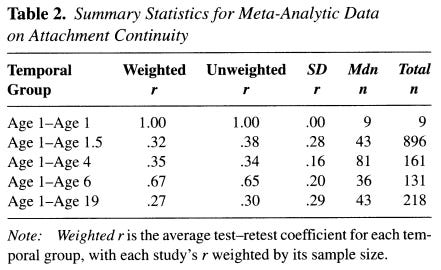

However, there is probably a lot of unreliability here and these numbers might be biased downward. Let’s look at the table produced by the Fraley meta-analysis:

We expect the correlations to decay over time as attachment patterns change. However, this is not the only reason the correlations may be less than 1: we have two additional reasons for this. First, as the age 1-age 1.5 correlations show, kids may not be that consistent in these tests even within a few months. (You can safely ignore the correlation of 1 reported from “age 1 to age 1” – actually from 12 to 13 months. This is a from a single study with N=9). Our attachment measure doesn’t look very reliable. Second, as they get older, we have another problem. You cannot use the same behavioral methods to measure attachment anymore – teenagers, ideally, don’t cry when their mother leaves them alone – so you need to use other methods such as questionnaires, which come with their own biases. You expect both noise and methodological differences to push correlations downward.

Normally you can use the so-called Heise model to calculate reliability and temporal stability separately. This is because the lack of reliability biases correlations downward, but only once: you will be affected as soon as you do repeated measurements, but your T1 to T3 measurements will not be affected by poor reliability any more than T1 to T2. Instability adds up over time, but the lack of reliability doesn’t. See here for an excellent treatise and a demonstration of how extremely stable personality is. But here we have strange numbers: attachment stability is higher from 1 to 4 than 1 to 1.5 years, and even higher from 1 to 6 years, only to drop down again from age 1 to 19. This is probably because the correlations are estimated with noise or because of some methodological difference in the studies of different ages. In any case, no numbers will satisfy the equations in the Heise model. But the sudden drop from age 1 to 1.5 and the modest change afterwards suggests that attachment stability must be higher than what the raw correlations suggest. Attachment definitely has above zero temporal stability, possibly not even a bad one once you control for noise.

The benefits of good attachment

I found three large recent meta-analyses on the social benefits of good attachment, with the conclusion that better attachment is related to better social competence with peers, fewer behavior problems, and internalizing problems, mostly in children. These are not strictly speaking meta-analyses of longitudinal studies, so sometimes attachment and other outcomes could be measured at the same time, but from what I see this is not the case of most studies and the effect of time elapsed between measurements is not significant so it doesn’t seem to be an issue. The effect sizes are expressed in standardized mean differences, which makes sense given that attachment type is supposed to be a nominal variable: you attachment is either secure, insecure-avoidant, insecure-ambivalent or disorganized. They are quite modest, d=0.1-0.5, but we have the same issue of reliability that came up for temporal stability.

There are lots of other interesting single studies on this topic, for example this one. In 163 people, suboptimal behavior in the Strange Situation as 12-18 month old toddlers was associated with more health problems at age 32. There are many ways to p-hack a study like this, but this is an impressive dataset and I tend to believe what they found. The better kind of attachment measure – a rating of attachment security, as opposed to the arbitrary categories – was associated with all health measures the authors used, with p<0.01 for two out of three.

Overall, I think it’s hard to argue against the utility of attachment. Children who have poor attachment patterns early on really grow up to be older children and eventually adults with worse life outcomes across the board. This is in spite of the fact that we have unreliability on both sides of this equation.

Attachment genetics

We are on to something when we say that toddlers’ behavior with their parents is an important indicator. Despite a lot of noise in the measurements, it is reasonably well associated with later self-reports of attachments and other measures – sometimes reported by other people, such as peers, teachers or doctors – of wellbeing. But is this behavior really learned from the parents?

The classic way to find this out is a twin study. See, if parents make their kids behave in a certain way, this should apply to all kids they raise: theoretically even to adoptees, but as adoption designs are hard to do, it’s easier to look at monozygotic and dizygotic twins. If attachment style is caused by the parents, MZ and DZ twins should be equally similar in their attachment – they were, after all, reared by the same mother. However, if the truth is that we inherit a certain personality, we exhibit it even as toddlers and then it shapes our lives as we grow up, then MZ twins, being 100% genetically identical, should be twice as similar as ~50% identical DZ twins.

I did my best to find as many twin studies on attachment as I could (here is my collection). I mostly came up with the same studies Barbaro et al (2017) did a few years ago, plus a few more. These authors raised a similar point I do now: the numbers say that when it comes to genetic and environmental influences, attachment is like everything else.

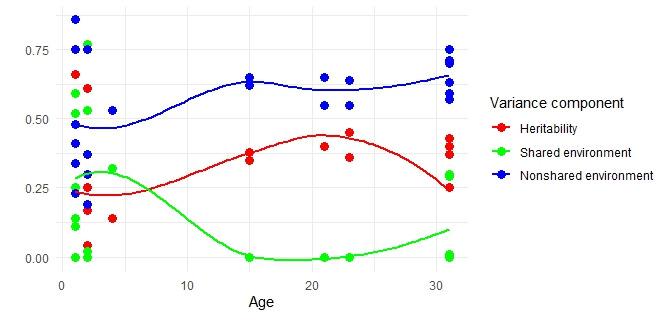

In babies and toddlers, MZ and DZ twins are about equally similar, showing the effects of the shared environment. Mothers really seem to affect the behavior of their babies. However, this shared environmental influence disappears in adolescents and adults, while genetic effects get stronger. This is a pattern that has been observed for many traits, including body mass index, various psychiatric problems and attitudes, and, most famously, intelligence (the Wilson effect).

We get this graph when we look at genetic and environmental influences on attachment over time:

Fit lines are with LOESS. As it is usual, shared environment drops and heritability increases from childhood to adolescence. Curiously, there is an increase in the nonshared environmental component. A possible reason for this is that the measures used in adulthood (questionnaires) are noisier than those used for babies and toddlers (observations or very detailed Q-sorting techniques). Out of the 12 shared environmental estimates in the studies I found, only two are non-zero in adolescents and adults, and both are almost exactly 0.3. Just like for any other trait, there is very little evidence that attachment – as well as it can be assessed with a questionnaire – is affected in any way by whatever parental influences we share with our siblings. Attachment is reasonably stable and reasonably well related to good life outcomes, but it doesn’t look like it’s something we learn from our parents. It is much more likely that our innate character shows itself even when we are toddlers, and of course it later fully blooms and exerts its influence on our fate.

Shooting at vampires

You might think that the given this data psychologists long abandoned the idea of parents teaching us attachment patterns and instead embraced a more genetically informed view. You would think wrong. In the social sciences, false beliefs are vampirical more than empirical – unable to be killed by mere evidence. People in this field have a strong tendency for activism and a preference for talking their way out of conflicting findings rather than updating theories which resonate well with their feelings but were proven wrong by data. Discussions about the sociologists’ fallacy – the belief that correlations between the characteristics of parents and their children is automatically causal – is like that talk about what plants crave in the movie Idiocracy.

In the early 70s, Ayn Rand ridiculed a certain Peregrine Worsthorne for claiming that “Family life is more important than school life in determining brain power. […] Educational qualifications are today what armorial quarterings were in feudal times. Yet access to them is almost as unfairly determined by accidents of birth as was access to the nobility.” In the past fifty years, many people tried to put a stake through the heart of the idea that we are randomly born into families which shape us into who we are (also known as the Standard Social Science Model, now gaslit by Wikipedia as an “alleged” model), but it keeps coming back from the grave. The specific vampire of family-created attachment styles hardly even bears any scars from previous hunters. This paper titled “The Development of Adult Attachment Styles – Four Lessons” was published in 2019 in the prestigious Current Opinion in Psychology by Fraley and Roisman. These are veterans of the field who wrote about quantitative issues, so they are not verbalist dunces. The paper invokes a textbook sociologists fallacy right in the first “lesson” it draws:

“Adult attachment styles appear to have their origins, in part, in earlier interpersonal experiences. […] For example […] at age 18, we assessed the children's attachment styles. We found that those who were insecure at age 18 were more likely than those who were secure to have had less supportive parenting over time […], to come from families characterized by instability (e.g., parental depression, father absence), and to have had lower quality friendships in adolescence.”

Yes, and smarter children also come from families from more books, so having books at home must be causal for high IQ!

The way the paper dismisses definitive genetic evidence that the mainstream view about the attachment development is wrong is also worth reading:

“On the one hand, behavior-genetic research involving twin samples suggests that attachment styles are heritable. […] On the other hand, efforts to identify the specific polymorphisms and gene-environment processes has proven challenging. As we have noted elsewhere, this “mystery of missing heritability” is becoming more salient in psychological research. It might be the case that researchers simply need more time to identify the right genes, the right epigenetic processes, or the right additive and nonadditive combination of genes. Regardless, there is a lot to learn by bringing a genetically informed perspective to close relationships research more generally, and adult attachment research in particular.”

From what I have seen, other recent reviews and book chapters (for example, here and here) either don’t even mention genetic influences on attachment, or treat genetics as an interesting new trend that doesn’t seriously challenge the idea that attachment is something learned by small children for life. Attachment theory still needs its Van Helsing.