A Copernican Revolution: the Ukrainian war

The case for immediate ceasefire – for everyone’s sake

In the first two entries of the Copernican Revolution series I strictly dealt with scientific methods to answer societal questions. I try to steer away from straight-up politics as much as possible, but I will make two exceptions, and this is one of them. Science relies on the dispassionate analysis of facts, which is unusual but maybe not impossible in politics. Even more importantly, science has by necessity developed ways to deals with uncertainty – nothing is ever settled, but new observations make certain theories more or less plausible, just like how everything is possible in history but certain things more or less so. In this piece, I try to apply these principles to a geopolitical analysis of the Ukrainian war. In short, my conclusion is that it is hard to imagine a scenario in which an immediate ceasefire along the current contact line is not the best outcome for all parties, possibly excluding the United States.

It is unusual to write a war analysis 1) without partisanship and 2) without being a war nerd, that is, focusing on which technical military capabilities each party has. In other words, it is unusual to write war analysis with common sense. In war, as anywhere else, we don’t know what will happen but there is a range of possible outcomes, each with some level of desirability and probability. It’s pointless to pursue outcomes which are very unlikely even if we want them very much.

Partisanship clouds our judgement and makes unlikely but desirable outcomes seem less out of touch. Common sense, on the other hand, dictates that we must sometimes be content with a less than perfect solution to a problem because with every attempt to get a better one we would be digging ourselves into a deeper hole. I think that – contrary to popular wisdom on all sides of the conflict – the least bad outcome for all parties in the Ukrainian war is immediate ceasefire. Here is my case for it.

Victory conditions and the escalation lottery

Great powers sometimes have ideological, grand strategy goals with their wars. It is certainly the case with this war. We will soon look at the geostrategic consequences of the ceasefire idea, but as the citizen of a small country in the neighborhood, my principal concern if this war is winnable.

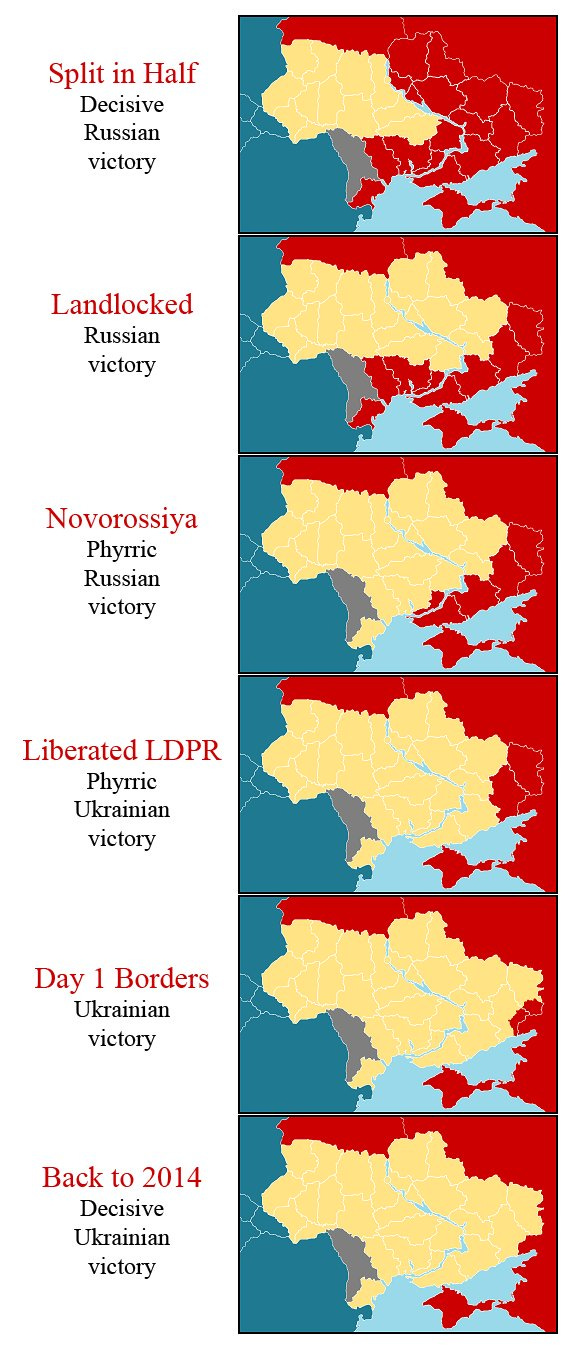

What is “winning”? Early in the conflict (just before he decided to become a globalist) Russian blogger Anatoly Karlin posted this image (the Chatham House has similar analyses even now):

This is a nice summary of what each conclusion of the conflict would be perceived as, with the qualification that Ukrainian goals are maximalist: they call not for zero territorial cessation at a minimum. For Ukraine, even Karlin’s “decisive Ukrainian victory” is a pyrrhic Russian victory because it leaves Crimea with the enemy. Russian victory conditions are murkier but they don’t include completely occupying Ukraine. Russia annexed five Ukrainian provinces so keeping those is probably a minimum wish for them. These correspond to the “pyrrhic Russian victory” scenario on the map, although the Russians don’t control the provinces outside Crimea completely.

I looked at Metaculus (this, this and this question) and created a colormap of Ukraine showing the probability of community-predicted Russian control for 2027-2030 (depending on the question but mostly 2027):

To make the extrapolations nicer, I copied some predicted probabilities to adjacent cities (for example, 0.01 predicted for Kiev to Zhytomir or 0.04 predicted for Mikolaiv to Kryvyi Rih) and added 1 to Russian-occupied cities firmly behind the frontline such as Mariupol. (There is no Metaculus prediction for Mariupol but the Russians spent enough of their money on reconstruction to take this as a strong bet.) The thick isobar line runs at 50% predicted Russian control and very close to the current front. If you look at the raw numbers on Metaculus, they drop off rather sharply on the sides of this line: the community predicts a frozen conflict. The worst outcome would be to keep fighting roughly along these lines for several more years. This way, both Russian and Ukrainian soldiers would die and EU/US money would be wasted for nothing. Note that even if you don’t mind Russians dying you are still sacrificing Ukrainians for this (and vice versa). It only makes sense to keep fighting if you expect a better outcome for your side. There are ways to achieve this, but they come with significant risks.

For Ukraine, the only reasonable way to victory would be to get NATO troops involved. I think this explains the strategically irrational choices they make by invading Russian territory and provoking the Russians with humiliating but strategically irrelevant rocket attacks on their home turf. You can think of it as an escalation lottery, if they poke the Russians hard enough they might strike back with something (like a tactical nuke) that provokes NATO to send troops. Just like the real lottery, it’s a very stupid game though because they must continuously swallow costs for an uncertain payout. Also, unlike in the real lottery, they can win too hard: getting nuked (or hit hard by any kind of Russian retaliation) is not great, and NATO involvement can mean nuclear Armageddon. The Ukrainian side is fighting for an unlikely reward with a strategy which can mean catastrophe just as much as success. Continued fighting is a bad deal for the Ukrainians (not to mention their Western allies who shore up the costs).

The Russians are slowly gaining land, and the Metaculus map actually gives them about 50-60% to conquer Sloviansk and Kramatorsk, the last two major cities in Donetsk oblast which they claim. But the same map gives them almost no chance to conquer the capitals of two other claimed oblasts (Zaporizhzhia and Kherson). A continued war may be slightly more beneficial for the Russians, but even they would have to absorb heavy losses for very limited gains and risk NATO involvement. Because they already have the juicy parts of the provinces they annexed (the Black Sea coast and the main cities Mariupol, Donetsk and Luhansk, including reasonable buffer zones), a status quo ceasefire should be an acceptable outcome for them.

From a practical point of view, neither side has much to gain from fighting, but heavy losses are guaranteed. It is pointless to wage war without a reasonable expectation of victory. A few weeks ago there was a huge scandal in Hungary when a government official said that we would have been smart enough not to stand up against the Russians like the Ukrainians did. He was of course completely correct, and not just in theory. When the Russians last invaded us in 1956, we stood down after minimal fighting, which kept the country intact for a relatively successful Communist period and ultimately a democratic transition when the climate was right and the Russians left on their own. Destroying the country in a futile attempt to resist and get the same occupation would have been stupid.

But what about consequences? What about the sanctity of borders? What about normalizing gaining land by invasion? Won’t the Russians steamroll the Baltics, Poland and Western Europe after winning in Ukraine?

Invasions and frozen conflicts

We have now gotten to the geopolitics of the war, which is normally beyond the pay grade of small state citizens like me. Arguments against the ceasefire are that it 1) sets a bad precedent, normalizing changing borders by invasions and 2) fails to resolve underlying issues (such as Russian militarism or the eastward expansion of NATO). I think these are mostly moot, but let’s take a look at them.

One argument why the war must continue is that otherwise we are setting a precedent for taking territory by invasion. If Russia wins, no matter the cost, any country will be emboldened to launch invasions against neighbors because the precedent has been set that the international community will be OK with the status quo you establish by arms. This argument effectively makes Ukrainian victory more valuable and thus worth pursuing even at lower odds of victory.

This argument needs to be taken seriously. Invasions used to be common but became rare, in part because they have a flatter cost-benefit ratio (wars became expensive and simply capturing territory became less lucrative) and in part because of the dedication of other nations to condemn them. (Read Richard Hanania’s essay on this.) Preventing warfare is important so anything that does it successfully needs to be given strong consideration.

However, the argument assumes that, at least after World War 2, there is a line drawn in the sand: these are the final borders, nobody gets to invade to change them, and Russian success in Ukraine would invalidate a 80-year precedent on this question. My problem is that no such precedent exists: lots of nations, including the United States itself, did thing similar to what Russia is doing, even after World War 2.

The most successful invasion would be if the invader could get the international community to legally recognize the territory he occupied. Even this has almost happened: in 2019 the US (although not “the international community”) did recognize the Golan Heights, a Syrian territory occupied by Israel in 1967. A second close example is Kosovo, which broke away unilaterally from Serbia after a war and NATO intervention in 1998-1999, supported by the US. Kosovo is widely recognized as a country internationally and the original independence movement would have been clearly suppressed by Serbia without NATO intervention, so the independence of Kosovo can be considered to be a second case of territorial change resulting from military invasion. Interestingly, the EU countries not recognizing Kosovo are those with large ethnic blocks who could break away if we took the Kosovo precedent too seriously: Spain (with the Catalans and Basques), Slovakia and Romania (both with large Hungarian ethnic blocks).

I don’t think Russia hopes to gain international recognition for its Crimea and Donbass acquisitions. It would be happy with de facto control with other countries tacitly accepting its control. If we lower the bar to this level, we find even more examples of the international community being basically OK with invasions:

- Northern Cyprus: perhaps the most egregious example. Turkey invaded Cyprus in 1974 and created a breakaway state in the north of the island which nobody else recognizes. Not much happened to Turkey because of this. Although it was already a NATO member, it started EU (technically EEC, the predecessor organization) accession talks in 1987. In 1974, the US needed strong allies in the Eastern Mediterranean and this was more important than the borders of Cyprus.

- Nagorno-Karabakh (Artsakh): this was an Armenian-majority autonomous province within the Azerbaijan SSR of the Soviet Union. During the fall of the Soviet Union, the population voted for independence and joining Armenia, which the Azeris opposed. War broke out and the Armenians won, so Artsakh remained a de-facto independent (although not internationally recognized) second little Armenia until Azerbaijan recently re-took the whole area in an invasion. The international community did not have strong opinions about either the Armenian or the Azeri invasions. During its independence, Artsakh had talks and some diplomatic relations with the US and the international reaction to the 2020 was mostly just to call for ceasefire and as few causalities as possible.

- Rojava: officially the Autonomous Administration of North an East Syria, a Kurdish quasi-state which emerged during the Syrian Civil War. Kurds mostly live in Turkey, Syria, Iraq and Iran, they have long wanted to have an independent state and they have some history of self-administration in all four countries. When the Syrian Civil War broke out, the Syrian government under Assad (internationally recognized, but opposed by the US) had its hands full fighting jihadists and other rebels so they largely left the Kurds to their own devices. The United States, on the other hand, supported them militarily. Although the war is mostly over (or so it seemed when I started writing this), Syria is still divided, and the Kurdish territories are de facto independent. The US keeps troops stationed in Syria, pillaging the oil fields there while keeping the official Syrian government under heavy sanctions. The international community was also OK with Turkey invading Kurdish-controlled Syrian territory in 2016-2019, keeping troops and running civilian life there.

My goal with these example is not to say that Russia is no worse than Armenia, Serbia, Turkey, or the United States, or any other country. I’m also not trying to compare, relativize or normalize these invasions or wars. My point is that there is no red line that Russia crossed in 2022, let alone 2014: there are numerous late 20th century examples of border changes resulting from military action with little reaction from the international community. The “no invasion” argument is selectively enforced depending on whether the United States cares about a certain incident. Regardless of what we think about territory-gaining invasions, strong countries will probably forever keep invading weaker ones to create buffer zones and achieve other geopolitical goals.

A version of the “stop the invasion” argument is that if Russia is allowed to take Ukraine, it won’t stop there: just like when Hitler invaded Poland and eventually the Soviet Union after getting away with annexing Austria and the Sudetenland, a successful Ukrainian adventure will embolden Putin to take the Baltics, maybe the former Warsaw Pact countries, and eventually maybe even move on to the Atlantic. This is certainly possible, in the way a world-ending asteroid strike or a Black Death-style new pandemic is possible: there is a future universe where Russia gets strong enough to steamroll all of Europe. But it is irrational to overprepare for low-probability events. Current, stated Russian goals call for the “demilitarization” of Ukraine and limited occupation. Betting markets and the battlefield situation say they are not capable for much more. If we are afraid that the Russians will keep expanding west in the future for some reason, we should build serious militaries in Europe (now that the normal way of preventing wars, economic codependence, is gone for a long time). That doesn’t cost lives, and the monetary costs are spread across many years. Feeding more money and Ukrainian recruits to the war machine is like selling all your investments to build an asteroid-proof shelter.

What about the second argument against a frozen conflict, that it doesn’t solve the underlying issue and only lets the parties rearm for round 2? This argument always baffled me: how is a possible war in the future not obviously better than a real war right now? Besides, frozen conflicts have a good track record for preserving peace. Of the 9 frozen conflicts I can think of (China/Taiwan, the Koreas, Artsakh, Northern Cyprus, Transnitria, Abkhazia, Artsakh, Kashmir, Western Sahara) only two (Artsakh and Abkhazia) resulted in renewed wars, and in the former case there was a generation of peace. When the conditions were right, sometimes both sides of the armistice line developed into reasonable nice countries, as in China/Taiwan and in Cyprus. After a frozen conflict, Ukraine would still have most of its territory intact, it would have a port, and access to the EU markets. Russia would have the territories it can claim to be ethnically Russian, a defensible land bridge to Crimea, and maybe some economic re-normalization with the EU which would also be very important for the latter. Absent Ukrainian irredentism, there would be little immediate motivation to restart the conflict for a long time.

War profiteers

At the end of the post, it’s important to say that there are a few entities who would indeed benefit from a continued conflict. Unfortunately I think they have much more influence than those whom the war actually affects.

The most obvious of these is the military-industrial complex. The war is a great demonstration for all militaries in the world, they get to see in real life what the modern battlefield looks like and how their own equipment would perform. Weapon systems that work well generate sales. Military stock sent to Ukraine by Western militaries must be replenished. Politicians, career soldiers and industrialists in both countries make a lot of money on the conflict so they have little motivation to stop.

A less obvious one is the United States. The war is very cheap for the US: it is not affected by the loss of the Russian market and Russian resources, it sends old military stock and the money spent on replacements are a stimulus to the economy. There are no American soldiers dying in the war. On the other hand, the benefits from the war are huge. Weakening Russia is an obvious win, but not the only one. Maybe this is not obvious to Americans but beside Russia and China the EU is also a geopolitical rival for the US. The US has both raw materials and human capital, but the EU only has the latter: many raw materials like energy used to come from Russia which is now gone. The war caused an economic crisis in Europe, European industries are not profitable anymore compared to the Americans and the Chinese. The EU has little hope to become a competitor for the US either economically or militarily. Cynically, the US weakened two of its rivals at once by pretending to be allied with one of them. If you are American, you want your country to be geopolitically dominant and don’t care about the cost of this on Europe, Ukraine or Russia, you actually have a good case against ceasefire in Ukraine.